On my last day in Kakuma Refugee Camp, a scorcher in late May, I climb on the back of a boda-boda — the camp’s cheap, impromptu motorcycle taxis — for a ride out to the farthest frontier of the camp, an area called Kakuma Four. At my side is Ed Grode ’71M.A., a retired school principal from Fairview, Pennsylvania, and president of the state’s Notre Dame Club of Erie, who is deeply engaged on refugee issues and working on a documentary about life in the camp. Also along for the ride is Jean-Michel, a 23-year-old Congolese refugee, an aspiring film director and Grode’s cameraman. Jean-Michel grips his bulky video camera tightly with both hands as our motorcycles speed down the badly rutted dirt road.

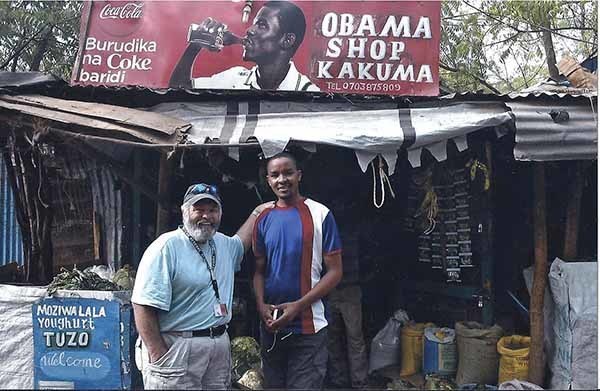

Grode is 67 years old, an avuncular bear of a man, barrel-chested and gray-bearded, with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of bad jokes and self-deprecating stories. He’s been coming to Kakuma since 2003 and began shooting his documentary last year to impart some of the harsh realities of African refugee life to the folks back home. The film is still pretty rough but makes a heartfelt case for allowing more refugees into America through a process called resettlement.

The United States accepts around 70,000 refugees per year. While that’s more than any other developed country, it’s still just a tiny fraction of the more than 17 million refugees now tallied globally by the United Nations. Grode argues, without sanctimony or self-righteousness, that the United States can do better — and the result will be a net win for the country. “Refugees start new businesses, they take jobs nobody wants, they pay taxes,” he says. “They’re survivors. They want to work hard and do the best they can.”

- Related articles

- The Place Called Nowhere

Our drive to Kakuma Four takes about 30 minutes but feels much longer on the dusty, crowded roads. The United Nations created Kakuma in 1991, and it has steadily sprawled out since then into a shape resembling an elongated inkblot. While some older parts of the camp are well-established, almost like a typical Third World slum, Kakuma Four feels highly provisional — just tents and mud-brick structures thrown up on a baking desert plain. This is where the newest arrivals are settled, mostly South Sudanese fleeing a catastrophic outbreak of political violence in their troubled homeland.

We stop at a cemetery with a few dozen fresh graves, mounds of dirt and sand with crosses and grave markers made from twigs and scraps of plywood. The cemetery wasn’t there the last time Grode visited, six months ago. “That knocked me for a loop,” he tells me later. “So many of the graves are for children.”

There are no simple answers for the millions trapped at Kakuma and similar camps. As U.N. officials often say, only political settlements that end wars and conflict can truly mitigate the global refugee crisis — and such settlements are rare and hard-won. In the meantime, global humanitarian aid budgets are stretched thin, and polarizing immigration politics in the United States and Europe make boosting resettlements a tough sell.

These large-scale challenges are something Grode understands well. He sits on the board of directors for the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI), a national nonprofit that partners with the State Department to resettle about one out of every 10 refugees admitted to the United States annually. As a board member, he helps set policy and steer the organization’s response to the constantly shifting global refugee picture.

This wide view can be dispiriting, Grode says. “It just keeps on keeping on,” he says. “There’s nowhere to put everybody.”

He stresses that his work with USCRI is totally separate from his involvement with Kakuma and the documentary film. When he visits Kakuma, he says, it is simply as a private citizen. It’s an important point, because his film depicts his deep, personal connection with an extended family of Congolese refugees whom he met during his first visit to the camp in 2003. He has stayed in close touch ever since. Another friend is Jean-Michel, his cameraman, who earns a little money every month shooting wedding videos on a borrowed camcorder.

About six years ago, with Grode’s help, part of the family — Alex and Clarice Nyachumbo, and their two daughters — resettled in Erie, where they are doing well, he says. The elder daughter recently enrolled at the local Catholic elementary school and plays soccer, while Alex drives trucks long distance and saves money for business school.

For the rest who remain in Kakuma, they live on in their cramped, dirt-floor compound, biding time as their applications wind through the resettlement bureaucracy. When they might get out is impossible to say: Just 1 percent of refugees qualify for resettlement every year, and the average stay in the camp is around 10 years.

Grode plans to return to Kakuma as long as his Congolese friends remain: Their hopes and heartbreaks are now his as well. “This isn’t happening to strangers anymore,” he says. “It’s happening to family.”