A plate of cookies sat on a table by the door, half-empty by the time I arrived. Mini-muffins in a plastic tray. Coffee in cardboard boxes and a stack of clean paper cups. I didn’t dare pour one for myself because I was late, having walked halfway around McCourtney Hall, angsty and out of breath and unable to find the “auditorium.” Plus which, I’d never been to a doctoral defense before — not as a graduate student half a lifetime ago, and not in the 11-plus years since I started working in higher education.

New territory. All my sensory receptors screamed, “Shut up and sit down before someone takes the podium!”

So I did. And as I slipped my coat onto the back of a chair and scanned for familiar faces, I saw an acquaintance from the library, and my nephew-in-law, Peter Deak ’17Ph.D., and the profiles of several biology professors I recognized from media releases about their research.

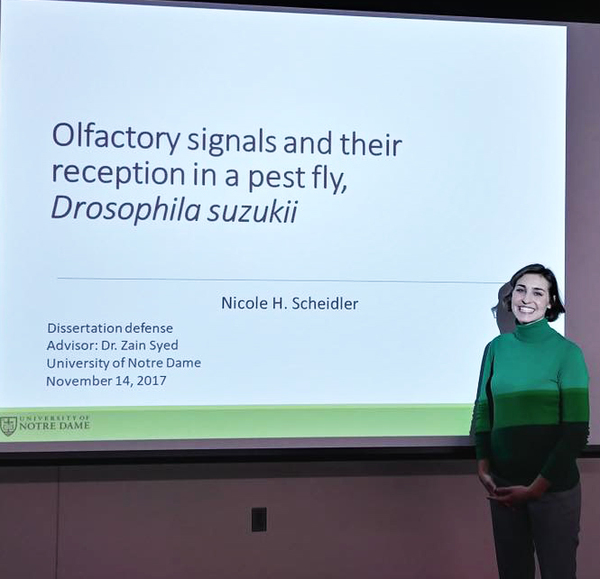

And there she was. Nicole Scheidler Deak, my niece by marriage, looking smart and confident in her green sweater — that shade of dragonfly-wing green being her favorite color and a sign of her determination to hurdle this milestone of learning and accomplishment and young life, full-tilt. She was tweaking something on a laptop. Up on the screen was the first slide of her presentation: “Olfactory signals and their reception in a pest fly: Drosophila suzukii. Nicole H. Scheidler.” Et cetera, et cetera.

I braced myself for 45 minutes of things I wouldn’t — couldn’t — possibly understand, knowing it would just feel good to see Nicole doing her scientific thing, sharing research findings and insights with representatives of a discipline into which she’s been emerging for the last five years. And then, ZAP! It’s a summer afternoon in 2012 and we’re standing in the parking lot outside her apartment building in Mishawaka, and she’s trying to figure out how to unlock the rental truck so we can unload her stuff and climb the stairs and unpack forks into kitchen drawers.

To my kids she’s Cousin Nicole. Or Cous-Ant Nicole, because she’s enough older than many of them to feel more like an aunt than a cousin. The kids were eager to lift and carry and run down the ramp and check out her view of the duck pond from the balcony off her new living room. And in my memory she’s standing in that living room, age 22, wearing the graphic T-shirt we’d laugh about off and on from that day to this. The one with the stick figure thrusting an Erlenmeyer flask into the air with one hand and a calculator with the other. The one that says, “Stand back! I’m going to try science!”

An enthusiastic college graduate ready for post-graduation life. Stand back! Regard Creation with awe and wonder! Explore! Learn! Share! That’s Nicole.

In the five years since, her Aunt Alicia and I have added two more children, and Nicole’s added countless thousands of hours of meticulous, time-intensive scrutiny of these little Asian buggers that go for fruit when it’s still ripening instead of waiting politely for it to rot on your counter, like Drosophila melanogaster and the rest of suzukii’s tiny, winged cousins do.

We couldn’t believe it when she’d settled on fruit-fly research in her first weeks of her first year in the program. It was her first lab rotation. She didn’t hesitate. Here I thought she’d pick up on apes or elephants or something else appealing — at least to me. Because, really. Fruit flies? For a whole year, I’d ask how her “mosquito” research was coming along and she’d stare back at me with a certain kind of droll Nicole expressionlessness that conveyed both patience and pity. But as the months sailed by, I could see the patience draining from those intense green eyes and the embarrassment rising in mine. Fruit flies, Uncle John.

In years two, three and four, Nicole went through the predictable tunnel of love-hate darkness that harries all graduate students regardless of the object of their studies. Her dissertation adviser and principal investigator, Dr. Zain Syed, would say that mentoring Nicole, his first doctoral student, not only taught him how to be a mentor, but how to be a better parent to his own children.

We’d hear her tales of woe when she’d come for dinner or a birthday party or baptismal reception. Most of the time, really good. Sometimes, bad. Like, “I want to leave and teach high school” bad. Not that there’d have been anything wrong with that — apart from the abandonment of her goals.

And there she was up in front of a room, presenting her work, speaking without notes, laughing at herself when she made some common word-choice mistake. Authoritative, fluid, masterful, brilliant.

But here’s the astonishing part.

I actually learned things. What I didn’t expect from the public defense of a doctoral dissertation in biology is that the same bright young mind who needs to address the older, wiser minds in the room can do so in a way that teaches the rest of us, brings us all along from hypotheses to findings.

I learned that fruit flies aren’t actually all that interested in fruit — the annoying clouds of them that attack my wilting grapes in August notwithstanding. No, they’re after the nutrition they find in the yeasts that gather on the fruit.

I learned that male D. suzukii have spots on their wings. Females don’t. This knowledge comes in handy regardless, but especially so when you’re trying to figure out which ones are responding to which yeasts inside your specially designed experimental control equipment.

"My fly": A male drosophila suzukii, photo by Nicole Scheidler Deak '18Ph.D.

"My fly": A male drosophila suzukii, photo by Nicole Scheidler Deak '18Ph.D.

I learned that D. suzukii is a late addition to the fruit-fly horde that’s come to America in recent decades and that their unique appetite for fresh fruit poses a serious threat to our fruit-growing economy. Like the berry farmers in southwestern Michigan who make summertime in South Bend such a nonstop special treat, or the California cherry growers who contributed money to Nicole’s study.

I learned that these minuscule pests have hundreds of terrifying quantities of odor receptors on their antennae and hundreds more thanks to the maxillary palps of their, er, mouthparts, which look really gnarly to me — Nicole, over brunch, would say a-MA-zing! beautiful! — when scaled up a few thousand times larger than life.

I learned that it’s possible to remove these sensory organs, one or the other or both, in the process of trying to determine which yeasts most allure the flies, and how and why. (Those surgeries were done as humanely as possible, Nicole later assured me. Anesthetized with ice. Yeah. I cringed. But that post-op.)

As good a teacher as Nicole is, I got lost along the way, my comprehension limited by the meager scientific understanding that walked into the room with me. I did grasp that my niece hasn’t fully solved the olfactory mysteries of D. suzukii, but has neatly laid out avenues for further discovery.

That’s basic research. Eventually the idea is to match this new knowledge with future findings in the search for ways to discourage these fruit-chomping machines from their destructive and costly feasting.

Then she was gone. Disappeared into a smaller room where the scientists could grill her on the finer points for another hour and a half while the rest of us returned to our own Tuesday-afternoon labors.

Later that evening, we met Nicole, Peter — her husband of four months,— and several of their friends for drinks at a favorite bar in South Bend. Peter had defended his dissertation in the engineering of the diagnosis and treatment of allergies in April, and tonight he explains, celebratory Manhattan in hand, that there are now two doctor-couples in his extended family, but just as with the fruit flies there’s a nifty way to tell them apart. “We call the medical doctors the M.Deaks,” he says. “We’re the Ph.Deaks.”

That geeky-awesome kid we moved in five Augusts ago is now a bona fide insect biologist and a married woman. And we’re all really proud of her, I can tell you.

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.