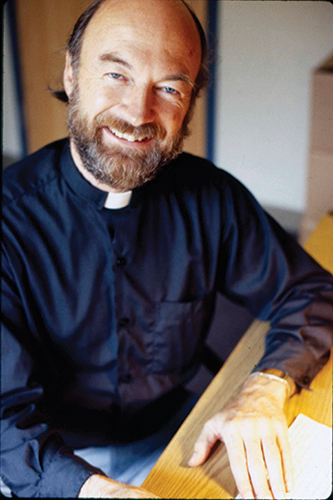

Rev. John S. Dunne, CSC, ’51, John A. O’Brien Professor of Theology, died Nov. 11, 2013, at age 83 after a struggle with complications from a head injury sustained in July. The Holy Cross priest, who joined the faculty in 1957, was one of Notre Dame’s most beloved teachers and respected theologians, the author of some 20 influential works on theology and the spiritual life. For decades his classrooms overflowed with enrapt students keen to his ideas as well as his inimitable lecture style — the pacing and pausing and spontaneous combustion of insight and revelation. Here is a reflection from one of the hundreds affected by his life.

When I went to Notre Dame in 1963 the Mass was in Latin. Four years later, when I graduated, it was in English. It was a huge shift in the life of the Catholic Church, but my encounter with the theology of Father John Dunne was a constant throughout this time. His studies revealed a depth to the meaning of Christianity that made many subsequent debates about “the Spirit of Vatican II” and “traditional Catholicism” look pretty shallow.

I had heard about John Dunne before entering Notre Dame. At a dinner that included Father Leo R. Ward, a Notre Dame professor of philosophy, one of my uncles asked Ward if John Dunne was as good as he had heard he was. “Oh, yes,” Father Ward said. “He’s the best of our young theologians and already quite bald.”

He was that, and he was a wonderful teacher. Most people I know who took his classes have read at least a few of his books and, as good as the books are, we tend to agree that his classes were much more exciting. What he communicated to me was that what he was talking about was truly a matter of life and death. It was our job as human beings to get headed in the right direction. His first book, The City of the Gods, posed the question that informed all of the rest of his work: “If I must someday die, what can I do to satisfy my desire to live?”

One of the marks of a good liberal arts education is when you encounter a moment that rings true in terms of what you were taught, when something someone said years ago illuminates what you are living. This happened to me more than once as a result of John’s teaching. He spoke, for example, of the importance of “passing over” — of entering into the experience of others, including people from very different religious traditions, in such a way that you can understand what they believe with complete empathy. Far from dissolving your own religious commitment, he held that this practice helps you see it more clearly.

I was doing an article on Mormonism, as far from my own brand of Orthodoxy as you can get. But while interviewing a Mormon historian and his wife, I came to understand what had led them to their Mormon belief and the ways it sustained them, and I remembered John.

John looked everywhere for insight — to novels (he loved a book he’d learned of from some of us, a strange novel by the critic Herbert Read called The Green Child_), to film (_The Seventh Seal and other Bergman movies), to poetry and philosophy. He was almost a magpie when it came to what he put into his books, which made him a more interesting writer than most theologians are. A professor once gave me an essay he liked on one condition, “Don’t share this with John Dunne. He’ll use it.”

When I heard about John’s death I called a friend, Bill O’Brien, who was close to John. Bill had told me that in his later years John had devoted himself more and more to musical composition and the piano, something he’d always loved. I mentioned to Bill that the obituary Notre Dame issued included a moving story about a nurse who had come into John’s room near the end, where one of John’s former students was praying. The nurse asked, “Can I stay in here for a while? I feel God here.”

Bill reminded me that John had said you can learn about God in two ways: by looking at doctrines and dogmas, and by encountering God in the friends of God. Bill also reminded me of an important distinction John made between Buddhism, a generally nontheistic religion, and Christianity’s stress on God’s being with us. Buddhism speaks, not unwisely, of living in the present. Christianity emphasizes living in the presence.

Time and Myth, one of his best books, begins with what I consider the “Call me Ishmael” of theology: “What kind of story are we in?” I’ve thought of this often when looking at how God was manifested to us in the flesh and taught through parables, stories like that of the prodigal son, the merciful father and the resentful obedient son; of the Pharisee and the publican; of Jesus’ own life, and Paul’s.

And ultimately John’s story, and all of ours. I am reminded of one of John’s classes in particular. Instead of beginning his planned presentation he said, “We talk about how God answers prayers, and he certainly does — but I can tell you, sometimes prayers are answered fantastically.” He said this with such firmness and joy that it was clear he had encountered something wonderful.

I never dared to ask him about something so personal, but it delights me to think that, now, he is in that presence.

John Garvey is a priest of the Orthodox Church in America, a columnist for Commonweal and author of Seeds of the Word: Orthodox Thinking on Other Religions and Orthodoxy for the Non-orthodox.