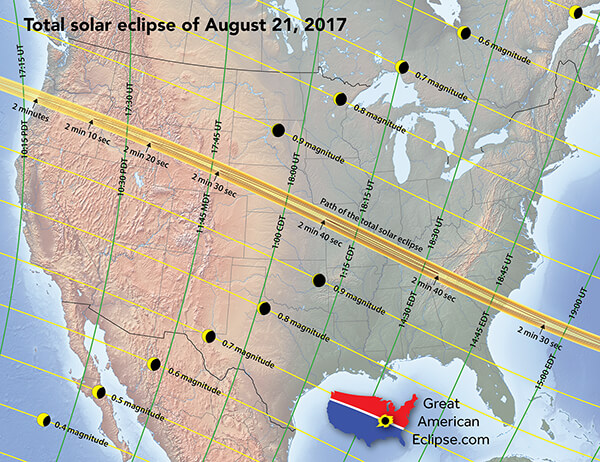

On Monday, August 21, 2017, America will witness one of nature’s grandest spectacles. The “Great American Eclipse,” as it is being called, will be the first total solar eclipse visible from the continental United States since 1979, when a massive shadow caused by the moon blocking the light of the sun passed over the Pacific Northwest. But this year’s eclipse will be the first total solar eclipse visible from coast to coast since 1918. Tens of millions of Americans are projected to make their way into the narrow path of the moon’s shadow — a seventy-mile wide swath of complete darkness stretching from Oregon to South Carolina — to watch the sun disappear completely for nearly three minutes over one section of the country after another.

Michael Zeiler, www.greatamericaneclipse.com.

Michael Zeiler, www.greatamericaneclipse.com.

As a child, I watched the 1979 eclipse while standing out on the blacktop of my elementary school. Years later, after I received my doctorate in history and philosophy of science from Notre Dame, I began researching an eclipse that occurred on July 29, 1878, over the Rocky Mountains. Tourists and astronomers flocked to that eclipse as well, braving the harsh conditions and high altitudes of the Western frontier in order to position themselves directly in the shadow path. As with the upcoming eclipse, in 1878 they would have seen the sun partially obscured from as far away as California or the eastern seaboard, but even witnessing a partial eclipse is nothing like the experience of a total solar eclipse, which can only be seen from within the track of the moon’s speeding shadow.

A total solar eclipse is a breathtaking sight. It lasts a few hours as the moon slowly crawls across the face of the sun, obscuring it bit by bit. But the most spectacular part of the eclipse is called totality: the brief period during which the sun is completely concealed by the moon. Totality lasts only a few minutes, but its effects are dramatic. The temperature plummets when the sun disappears, stars and planets become visible in the middle of the day, and on the surface of the Earth, a giant shadow up to 150 miles wide sweeps across the land at speeds approaching 2,000 miles per hour.

The effect of the onrushing shadow often fills those who see it with “primitive fear,” according to the psychologist and eclipse chaser Dr. Kate Russo, as a “wall of darkness comes creeping toward you.” In 1878, one observer, who watched the approaching shadow from the top of 14,000 foot Pikes Peak, described that wall of darkness as “pallid and ghastly . . . weird and terrible” as it devoured distant mountain ranges one by one. This year’s eclipse will speed across America in a little over 90 minutes.

Experts suggest that over 100 million Americans live within an easy day’s drive of the 2017 eclipse’s path of totality. Many hotel rooms within the path have been booked for over a year, and I’ve heard anecdotal evidence that those rooms that do remain are going for 10 times their normal rate — $750 in Wyoming and $800 in Tennessee. Thinking about camping? The National Park Service predicts tens of thousands of eclipse watchers will descend upon parks like Yellowstone and Great Smoky Mountains. State parks in the path will share the same fate. One park in eastern Oregon expects to host up to 50,000 eclipse watchers, and campsites have been auctioned off for as much as $2,000 each.

This won’t be the first time Americans traveled so far and (proportionally, at least) in such large numbers to see an eclipse. In 1878, the American West was only accessible by train. That didn’t stop eastern tourists from making the trek, arriving by the thousands in the weeks leading up to the eclipse — big numbers for the sparsely-populated West.

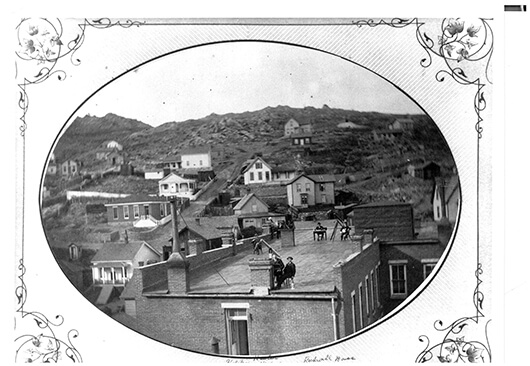

Astronomers prepare to observe the eclipse from the roof of the Teller House hotel in Central City, Colorado, courtesy U.S. Naval Observatory Library.

Astronomers prepare to observe the eclipse from the roof of the Teller House hotel in Central City, Colorado, courtesy U.S. Naval Observatory Library.

“Hotels are crowded with tourists,” Wyoming’s Laramie Daily Sentinel reported. As the event approached, bed capacity was soon exceeded. Some hotels set up cots and rented out any other available space. “In Denver are found such entries as these in the registers of the hotels," the newspaper continued. “J.E. Landholm, parlor; F.R.S. Wright, cot, dining room; H.B. Jenkins, billiard table.” In Colorado Springs, reported the local Gazette, “one of our popular landlords visited all the livery stables and engaged all the vacant stalls.” The hotels needed to turn no one away; if nothing else, guests were given a blanket and allowed to sleep outside.

Eye safety is important during an eclipse. Today, one can (and should, if they intend to watch the eclipse) buy a pair of inexpensive paper and polymer eclipse glasses. They cost only a buck or two, and are available online and in many brick and mortar stores. But in 1878, eclipse watchers made “smoked glass” — pieces of broken glass covered with a layer of soot collected over the open flame of a candle or oil lamp. “Smoked glass” was not nearly as effective or safe as today’s eclipse glasses; not only did smoked glass fail to block enough of the sun’s dangerous radiation, but the process of smoking glass had its own inherent dangers. In 1878, one Colorado woman, so eager to finish her smoked glass and run it outside to her husband in time, forgot to extinguish her lamp. She returned home to find her house in flames.

At the time, the transcontinental railroad was less than 10 years old, and the West was still in its “wild” stage. Only two years earlier, George Armstrong Custer and his forces had been crushed at Little Big Horn in Montana. So why did people risk so much, expend so much effort, just to see an eclipse? For astronomers, the reasons were scientific. For tourists, however, the reasons were sensational and even social: senators and shepherds, bankers and artists, all rubbed shoulders regardless of their station as they stared up into the sky. And, for many, their reasons were at least partially religious.

Back then, like now, witnessing something as glorious as a total solar eclipse could be a sacred experience. Coverage of the eclipse in the western press mingled scientific reporting and religious reflection without any hint of self-consciousness — such was the public role of faith at the time. A few days after the eclipse, the Colorado Springs Gazette invoked great English poets as it recalled the sublime spectacle of the sun’s sudden disappearance:

“The subtle influence of this scene on the observer cannot be described. We were all impressed with the thought that Jehovah lives and rules in the heavens. . . . It was not total darkness. A ‘dim religious light’ prevailed which told us of God’s glory and power. All could say with holy George Herbert: — Who hath praise enough? Nay, who hath any?”

That “dim religious light” (from John Milton’s Il Penseroso) was a reference to the solar corona, the sun’s envelope of glowing plasma only visible during a total eclipse. “Corona” is Latin for crown or wreath, and is therefore an easy celestial metaphor to transpose onto God.

The story of the 1878 eclipse — which I have come to call “America’s first Great Eclipse” — is so fascinating to me that I wrote a book about it. What strikes me in 2017 is the extent to which such religious sentiments still attach to the major scientific phenomena of our own time. A recent Washington Post article quoted astronomer and minister Hugh Ross: “I don’t think it’s an accident that God put us human beings here on Earth where we can actually see total solar eclipses. . . . I would argue that God on purpose made the universe beautiful, and one of the beauties is a solar eclipse.”

Casket vendor depicted in Colorado Springs Gazette of Aug. 3, 1878, courtesy of the author.

Casket vendor depicted in Colorado Springs Gazette of Aug. 3, 1878, courtesy of the author.

The same article also quotes those who believe the 2017 eclipse is a harbinger of the Biblical end times. The rest of us can take heart that those who expect the Rapture this August are not the first to hold such a view, and will therefore probably not be the last. In the 1870s things were no different. In Colorado, Millerites — followers of the teachings of the American Baptist preacher William Miller, who was convinced the Second Advent of Christ was imminent — believed that the 1878 eclipse signaled the end of the world. According to the Gazette, one enterprising citizen walked among the Millerites just before the eclipse, hawking wooden caskets. Tongue-in-cheek, the paper noted how the man carried a “sample coffin under his arm, and took a large number of orders at a twenty-five percent discount.”

The human capacity for wonder remains consistent across generations and centuries. More Americans will likely witness the August 21 eclipse than any in our country’s history. That so much attention is being drawn to it, and that so many of us plan on traveling to see it, reminds us that some things can still enrapture us, can draw our eyes away from our smartphone screens and give us reason to come together, be silent for a moment, and stare up at the sky — full of awe.

Steve Ruskin ’02Ph.D. is the author of America’s First Great Eclipse: How Scientists, Tourists, and the Rocky Mountain Eclipse of 1878 Changed Astronomy Forever. He lives in Colorado.