It’s easy to lose sight of the fact — especially at universities where theory is a favorite pastime and ideas often remain in the abstract — that design is everywhere.

Your cherished heirloom bedstead likely began as a pencil sketch on a sawdusted workbench. The toilet down the hall took shape on computer screens. The car you drive to work represents the conceptual and practical talents of dozens, maybe hundreds, of automotive designers.

Design defines the things we wear, sure, but it’s infused into the ways we eat, sit, sleep, keep clean and keep time, too. Work and play, prayer and ritual, safety, security, shelter. All of it’s shaped for better or worse by the way our stuff’s designed.

- Related article

- Student designs

Fortunately, we have among us a few who know what they’re doing. We call them designers, inventors, craftspeople, creatives — men and women who have learned to conceive powerful ideas and express them less in words than in the work of their hands. They are hardworking, mystical fusions of artist, engineer and tinkering humanist whose labors give form, meaning and comfort to products — and to the lives of those who use them.

Designers see. “The greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something, and tell what it saw in a plain way,” Ruskin wrote as if wandering the cosmos. “Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands can think for one who can see. To see clearly is poetry, prophecy and religion — all in one.”

Back on Earth, in a Riley Hall basement office near the studio where student workbenches teem with things like ball valves, dissected kitchen appliances and the plastic prototypes of their latest visions, Professor Paul Down of Notre Dame’s industrial design program equates design with organization. “It’s just about ordering things for a particular purpose or service,” he says. “Whether you’re getting on board a jet plane or just unlocking the door to your house, it’s all about solutions that weren’t naturally growing on the trees when man arrived on the planet.”

Each year a group of Down’s industrial design students — juniors mostly — enroll in the Product Design Research Project course he teaches with the help of such colleagues as Ann-Marie Conrado and Michael Elwell and shop technician George Tisten. They learn the language of materials and mass-production manufacturing processes, identify household problems that may be most acutely experienced by children, the elderly and the disabled, and then benchmark, brainstorm, think, draw, build, test and re-test their way toward product designs that offer innovative solutions.

While their peers meet educational epiphanies in London, Rome or Uganda, product designers’ eureka moments come on field trips to places like the JMS Plastics Inc. factory, about a mile from campus, where they get their first serious exposure to processes from injection molding to profile extrusion.

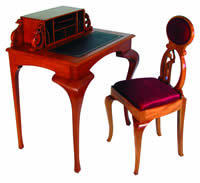

Across campus, in the similarly subterranean Bond Hall workshop of Professor Robert Brandt, furniture designers have received the same sort of illumination — sometimes even personal guidance on a project — from the staff of Cole Hardwood in Logansport or Johnson’s Workbench, a South Bend lumberyard and woodworking supply store.

For Brandt, design may lie somewhat closer to Ruskin’s artisanal predilections for hand tools and the earthier glories of wood. Students taking his four-semester Furniture Design concentration in the School of Architecture start with a “simple” table. It may be their first step from the two-dimensional drawings of their studies in classical architecture toward the work of genuine understanding that is the act of building in three-dimensions. They explore precedents — the Shaker style or the neoclassical American Empire and Biedermeier styles of the early-to-mid 19th century; distinctive later movements like the Arts & Crafts, Art Nouveau and Mission; or even standout contemporary designers — but Brandt reminds his students not to bind themselves up in tradition. “We don’t make antiques in here, so it’s got to be an original design.”

Each student presents Brandt with three to five ideas, and soon they’re machining their wood and reaching for the rasps, files, saws and sanders. “Craft to me is just expressing your idea with clarity,” he says. “If you look at something that is poorly crafted, you can’t get past that. You think, well, this isn’t much. But if something is crafted well, then you’re drawn into it. You start to understand the idea, the intent, clearly.”

Process and product make for quiet drama in the days and nights of the student designer, each year germinating some of campus’ most heartfelt accomplishments. Down thinks of the grin on a former student’s face after a breakthrough led to a design for a baby stroller that could both climb a curb and support the weight of an elderly or disabled pusher. Brandt recalls one student for whom building just “didn’t come easy.” At 3 o’clock on the morning of the review, she stepped back from her first project with tears of joy streaming down her cheeks.

Down’s students emerge with process books that anchor their portfolio and, not infrequently, earn honors from the International Housewares Association’s annual Student Design Competition. Brandt’s students, most of whom pursue careers in architecture with a sharper eye for the relationship between buildings and furniture, keep their finished tables, chairs, desks, mirrors, cabinets or clocks. For fifth-year architecture student Cristina Gallo ’12, the sense of satisfaction is incomparable. “It’s great to have something you can show people and say, ‘I can do this.’”

John Nagy is an associate editor of this magazine.