My memories of Mr. Burke point me in several directions, but there was one thing he did — a mere four words — that made a lasting difference in my life. All he said was, “I’m a quiet person.” But that has served me as a mantra for a lifetime.

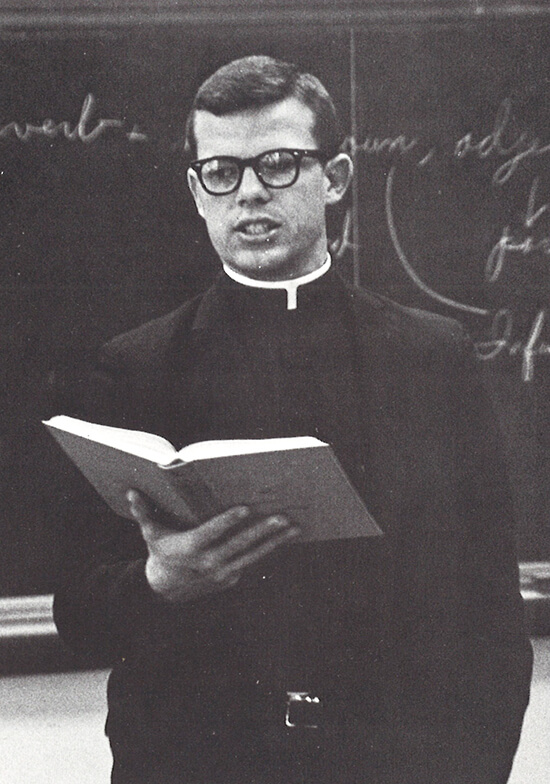

Mr. Burke was a “scholastic,” on his way to becoming a Jesuit priest. He taught at my high school in the mid-1960s, along with a half dozen other scholastics and six or eight Jesuit priests. It was an all-boys Catholic high school; Vatican II was in the air. Mr. Burke — Tom Burke — taught us English.

Part of the backstory here is that several years ago I wanted to make more of Thanksgiving than turkey and football games. I decided to thank somebody who had impacted my life, in some little way, and to express that gratitude by telling the story at this website.

My hope is that it leads others to actually thank someone at Thanksgiving, to use the holiday to extend appreciation to others for those random acts of kindness that mean a great deal.

This year I thought of Mr. Burke because of what he said to my dad while the three of us were sitting in the bleachers after a high school basketball game.

Mr. Burke was solid. He was not the most popular teacher at our high school, not the most dynamic or charismatic. But authentic, thoughtful, virile — a role model for young boys trying to find themselves in the turbulent 1960s. He was also physically solid, built thick, with a broad, tan face, strong cheek bones and pug nose that looked like it might once have been broken.

We liked it when Mr. Burke came out to football practice, working with the JV team as a middle linebacker on defense. He wore grey work pants, black Converse All-Star high-tops and a plain white T-shirt — his only equipment an old blue helmet with no face mask. And he mixed it up with us, was a rollicking, rampaging, rock’em-sock’em force on defense, smashing into the line, running down halfbacks, swatting passes away. Always with a grin on his face, having the time of his life.

I had him for freshman English, and again as a sophomore. He kept a carousel of books in the back corner of his classroom, a personal library of recommendations — the good books high school boys might read to get the real story on life, to learn the joy of real literature, to get us thinking outside our childhood perimeters.

He and I hadn’t talked, but one day between classes I was twirling the book rack, looking for something, and he came across the room, took a book off the rack and handed it to me. “I bet you’ll like this,” he said. It was The Catcher in the Rye. He knew me better than I would have suspected; the book was a life-changer for me.

I was, as the sayings go, “painfully shy,” “socially inept” and “awkwardly self-conscious,” an introvert afraid to speak, uncomfortable around others.

If that wasn’t difficult enough, I had a mother who wanted her son to exhibit the proper social graces, to display some Southern charm, to be conversant at least. But I was embarrassingly mute, despite all her proddings at social functions to tell the Johnsons, the Richardsons or the Carmodys some small story about my little life.

The divide between who I was and what she wanted me to be was simply too great a leap for my teenage self. And that was a pain and a yoke. And led to much self-incrimination.

One night after a basketball game, waiting for my teammates to emerge from the locker room post-shower, I sat near my dad who was sitting next to Mr. Burke — an awkward arrangement if ever there was one. And my dad, no great conversationalist himself, tried a few lame attempts to get some talk going, with no success.

Finally, he turned to the young scholastic and pronounced, “Mr. Burke, you’re awfully quiet tonight.” To which Mr. Burke looked at my dad and with a pleasantly serene face replied, “I’m a quiet person.”

That was it. I have never forgotten that.

It was later I fully appreciated the source of that response. Tom Burke knew who he was and was comfortable in that self-knowledge, that person, comfortable in his own skin. He made no apologies, favored no pretense.

And that gave me permission to be quiet, too, to rest in that awareness of who I am and not feel bad about it.

For years — in unfamiliar situations, surrounded by strange people, when ill at ease at meetings or stately dinners — I would say to myself, “I am a quiet person.” It was a reminder to pardon myself not only for my reserve but also for other deficiencies that make me who I am. Throughout my life, when I would feel that inner churning to perform or impress with words and social graces, I would calm those nervous trepidations by recalling Mr. Burke’s peaceful demeanor and his soothing declaration: “I’m a quiet person.” I am who I am.

And through the years I would also recall Tom Burke and those words as I tried to stay true to myself, to not lose the real me as I traveled along life’s way.

I don’t know what became of Mr. Burke. Like many religious in the wake of Vatican II, he left his community before his ordination. The rumor was that he had headed to the Canadian oil fields to be a roustabout there. But I never knew if that was true or merely wishful thinking on the part of Catholic school boys, for whom such an adventure suited Tom Burke — and our romantic notions of manliness and freedom.

Kerry Temple ’74 is editor of this magazine.