He didn’t have to enlist.

In the spring of 1917, the 30-year-old writer and father of four (with a fifth child on the way) put down his pen to fight in what was then called the Great War. Once more, his belief in the rightness of a cause shaped his thinking for the course he followed, and he was willing to risk one of the most promising writing careers of the early 20th century to take a personal stand.

Today he’s remembered for the sacrifice he made, for his commitment to Catholic literature — and for 80 words he wrote.

At the time — shortly after the United States declared war on Germany that April — Joyce Kilmer was one of the most respected literary figures in America. Poet, critic, journalist, he’d published six books since 1911, including three collections of verse. In 1913, to reduce the precariousness of a freelancer’s life, he joined the staff of The New York Times, frequently contributing to its Sunday magazine and book section.

Illustrations by Stephanie Dalton Cowan

Illustrations by Stephanie Dalton Cowan

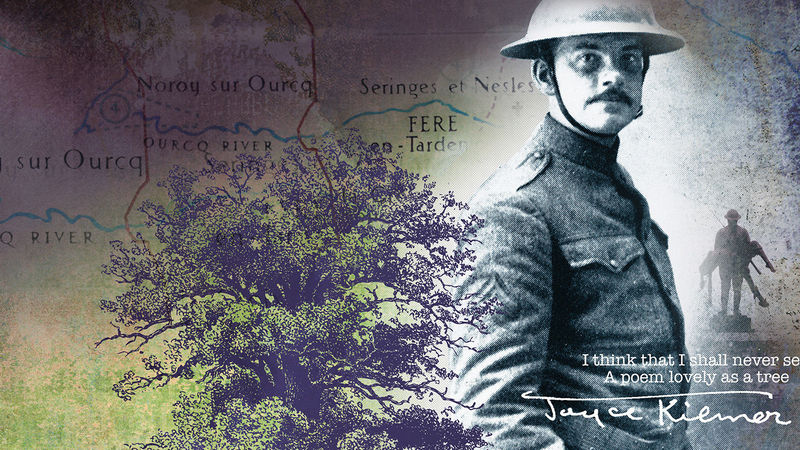

Even with a steady and applauded output, Kilmer became best known internationally for a 12-line poem that first appeared the same year he joined the Times. Simply called “Trees,” it begins:

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

The composition, with a predictable rhyme scheme and sing-songy quality, unfurls to a confessional conclusion:

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

In retrospect, what’s remarkable is that “Trees” came to public attention in the pages of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, which began publication in 1912 and featured the modernist, avant-garde work of T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and William Butler Yeats. Often reprinted or recited, especially as a classroom exercise through the first half of the 20th century, Kilmer’s arboreal alleluia became so popular that, in time, the poem overshadowed the poet — and much of his other writing.

“Trees” took root with its mass appeal the same year Kilmer converted to Catholicism. He embraced his new faith with a fervor extending beyond his spiritual life to literary endeavors. Poems and essays consistently explored religious subjects or themes, and he edited the book Dreams and Images: An Anthology of Catholic Poets.

Originally published in 1917 as Kilmer prepared to ship out to Europe, the collection has periodically been revised by other editors. As an indication of the initial editor’s stature, beginning in 1937 the title was changed to Joyce Kilmer’s Anthology of Catholic Poets.

Besides being a prolific writer in several genres, Kilmer established a reputation as a gifted speaker — either as a reader of his verse or as a lecturer about contemporary literature. He visited the Notre Dame campus in 1913 and in 1916, becoming friendly with Rev. John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, the University’s president from 1905 to 1919, and Rev. Charles L. O’Donnell, CSC, himself a noted poet, who served as president from 1928 until his death in 1934.

Kilmer’s lecture trips to campus prompted the widely circulated legend that a tree near the Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes served as the leafy exemplar for “Trees.” Actually, according to members of Kilmer’s family, the poet was gazing out the window of his home in New Jersey at a nearby woods when inspiration struck. A particular tree, much less one in northern Indiana, was never in mind.

But Notre Dame did make a definite impression on Kilmer. In the University Archives, there’s a copy of a letter he wrote that explained where he’d suggest sending “a young man” who intended to become a writer.

“If I were given a free hand in selecting a college for him, my choice would be not an Eastern college, but the University of Notre Dame, at South Bend, Indiana,” Kilmer said. “I know of no college or university in the country where English is taught so intelligently. Methods of teaching which are regarded as important innovations at Harvard and Columbia have been in use there for years.

“The students learn more than the theory of composition, they learn how to write — how to compose short stories, essays and poems. I know of no educational institution where a young man may get better equipment for a writer’s career.”

Kilmer, a 1908 alumnus of Columbia, even recommended that the prospective student contact Father Cavanaugh directly for additional information. Known for his active involvement in all aspects of the University, Cavanaugh taught English for many years and helped bring Kilmer, Yeats and other literati to campus.

Kilmer was fond of telling people he was 'half-Irish,' and he became incensed when anyone doubted his ethnic heritage.

Kilmer’s letter is dated April 10, 1916. Later that month, the Easter Rising — a rebellion against British rule in Ireland that resulted in 485 deaths and massive destruction in Dublin — shocked the world, including millions of Irish Americans. Did the revolt, which lasted almost a week and produced enduring repercussions, signal a new front in the Great War? Could the violent outbreak involve America?

As a journalist and poet, Kilmer played one of the most visible roles among Americans responding to the rebellion. He contributed two major articles about the Easter Rising to The New York Times Magazine. One focused on the involvement of poets; the other was an in-depth interview of a woman who participated on the rebel side before escaping to the United States.

Kilmer also published two poems supporting Irish independence. The last stanza of “Easter Week” unites his admiration for Catholic Ireland with his opinion that those killed during the insurrection or later executed by the British had died for a holy cause:

Romantic Ireland is not old.

For years untold her youth will shine.

Her heart is fed on Heavenly bread,

The blood of martyrs is her wine.

Since “Easter Week” appeared in 1916, it has been quoted and reprinted in many literary reactions to the rebellion. Kilmer took a foursquare stand siding with the Irish insurgents. Why?

His conversion to Catholicism no doubt played a part, and he relied on religious imagery to heighten his expression. But his own perplexing identity probably also contributed to his support of the rebel-martyrs.

Kilmer was fond of telling people he was “half-Irish,” and he became incensed when anyone doubted his ethnic heritage. In a letter to his wife, Aline, also a poet, he defended his putative Irish blood, instructing her: “And don’t let anyone publish a statement contradictory to this.”

There was just one problem. No family members and no friends have ever been able to find a Kilmer ancestor of Irish descent among all the Anglo-Saxons in the family tree. One granddaughter concluded her genealogical search by saying, “His passionate love for Ireland and the Irish is obvious, so we may say he was Irish by adoption.” His literary executor, the editor and essayist Robert Cortes Holliday, gently challenged the “half-Irish” claim of his confidante by remarking that Kilmer’s “birth was not exactly eloquent of this fact.”

To a certain extent, Kilmer became a self-made person — but not in the sense of the Horatio Alger myth of the late 19th century, promoting the belief that nose-to-grindstone effort at one’s work, along with ingenuity, would lead to material success.

Kilmer was different. Intentionally and with specific reasons, he made decisions about central characteristics of his life that he then presented to the public as the man he wanted to be.

Born Alfred Joyce Kilmer, he dropped his first name and went by “Joyce,” thus confusing more than a few readers about the gender of the poet they were reading.

Then, at the age of 26, he left the Episcopal Church and converted to Catholicism, a life choice with profound significance for him. In addition, during his 20s, he became — in the words of his son, Kenton — “enamored of Irish history, Irish legend and literature, and Irish and Irish-American poetry,” which probably explains his avowed, if adopted, Irish ethnicity.

In short, after personal deliberation Joyce Kilmer made a series of private decisions that shaped his public life and legacy. Being Catholic proved paramount to his identity, and championing an ethnic heritage with deep Catholic roots — as well as a fighting spirit — completed his self-portrait.

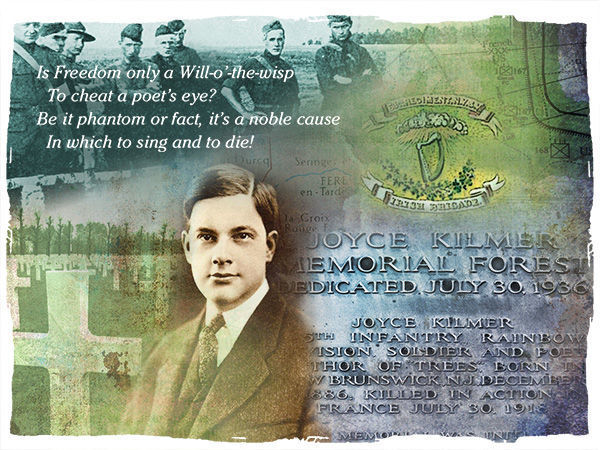

Almost immediately after the U.S. Congress declared war against the “Imperial German Government” on April 6, 1917, Kilmer joined the New York Army National Guard. Despite his support of Irish independence from the United Kingdom, having the U.S. become allies of the British in European combat made perfect sense for Kilmer, because freedom as a principle and way of life was, in his view, threatened and under assault. As he argued in a 1916 poem:

Is Freedom only a Will-o’-the-wisp

To cheat a poet’s eye?

Be it phantom or fact, it’s a noble cause

In which to sing and to die!

Not long after enlisting, Kilmer requested a transfer to the 165th Infantry Regiment. Popularly known from Civil War days by its earlier appellation as the “Fighting 69th,” this New York-based regiment was primarily made up of Irish Americans.

Kilmer felt at home in his new unit, observing in a letter before he shipped out to Europe: “The people I like best here are the wild Irish — boys of 18 or 20, who left Ireland a few years ago, some of them to escape threatened conscription, and travelled about the country in gangs, generally working on the railroads. They have delightful songs that have never been written down, but sung in vagabonds’ camps and country jails.”

Camaraderie counted to Kilmer, and, despite his age, college degree and other qualifications, he decided to stay as a sergeant in the 69th rather than become an officer in another outfit. At first a statistician, he shifted to intelligence while in combat on the Western Front.

Even with the rigors and vicissitudes of foreign warfare, Kilmer managed to write. One of his most affecting (and anthologized) essays, titled “Holy Ireland,” describes an evening that a dozen American soldiers spent with a French family after a 17-mile trek through snow on a “stormy December day.”

The acutely observed narrative quotes several Irish immigrants, now fighting for America, about their reactions to the singing of Christmas carols in Latin by their French hostess. “I tell you, Joe, it makes me think of old times to hear a woman sing them church hymns to me that way,” one says.

“It’s forty years since I heard a hymn sung in a kitchen, and it was my mother, God rest her, that sang them. I sort of realize what we’re fighting for now, and I never did before. It’s for women like that and their kids. . . . There used to be lots of women like that in the Old Country. And I think that’s why it was called ‘Holy Ireland.’”

Kilmer also sent back five new poems from the front, including “Prayer of a Soldier in France” and “The Peacemaker,” that held explicit religious — indeed, Catholic — appeal. He also wrote “When the Sixty-Ninth Comes Back,” a rousing salute to his regiment that composer Victor Herbert subsequently set to music. Near the poem’s end these lines stand out, particularly for anyone interested in tracing the nickname for Notre Dame’s athletic teams:

God rest our valiant leaders dead, whom we cannot forget;

They’ll see the Fighting Irish are the Fighting Irish yet.

The 69th did, indeed, return to the States on April 21, 1919, five months after the armistice ended the First World War. But Kilmer wasn’t with his comrades-in-arms.

During a reconnaissance mission on July 30, 1918, a German sniper shot and killed Kilmer near a farm beside the Ourcq River in the Picardy region of France about 70 miles northeast of Paris. He’s buried close by in the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery along with more than 6,000 other doughboys, most of whom perished during the war’s final months.

A simple white cross marks Kilmer’s grave, provides details about him and notes that he received the Croix de Guerre from the French government for valor. Next to Kilmer’s is an identical white cross with these words: “Here rests in honored glory an American soldier known but to God.”

It remains regimental tradition to recite 'Rouge Bouquet' at memorial services involving slain comrades.

Kilmer’s death became front-page news across America. In its dispatch, The Washington Post remarked that the slain writer was married with several children “but conceived that duty called him to the front.” The Sun reported to its New York readers that Kilmer was “the first of our well-known poets to fall since America entered the war.”

A week after the news about Kilmer appeared, The New York Times published a lengthy account by its drama critic, Alexander Woollcott, describing the battle in which Kilmer was involved and how the regiment responded.

Woollcott, then a correspondent for The Stars and Stripes and later a well-known contributor to The New Yorker, was accompanied on his search for Kilmer’s grave by Grantland Rice, the famous sportswriter turned Army volunteer who would coin the phrase “Four Horsemen” to describe the Notre Dame backfield of 1924. To show how Kilmer’s passing affected the newspaper’s readers, Woollcott’s article is followed by 11 poems and personal statements, honoring the writer’s life and career.

Harriet Monroe, founder of Poetry and an influential arbiter of early 20th-century literature, wrote in her magazine that Kilmer “had a singularly gracious and loyal character, and unusual personal charm. He was, as everyone knows, an enthusiastic convert to Roman Catholicism, and his best poems are enriched with deep religious devotion.”

Kilmer’s death made a strong impact at Notre Dame. Father O’Donnell, a professor of English and at the time a chaplain with the U.S. infantry in Italy, sent The Notre Dame Scholastic a memorial to his friend, “The Death Angel Speaks at Heaven’s Gate,” which presents the priest as the narrator to introduce “a sergeant” to St. Michael’s angelic cause:

. . . Michael of the Sword,

Admit him to your ranks and give command,

What bid you of valor, of virtue, of beauty, —

He has the level eyes that understand.

Students, too, reacted to Kilmer’s death, with Scholastic serving as the main forum for their responses. One senior wrote in the autumn of 1919 that Kilmer was “the greatest American poet of the last decade.” That judgment derived principally from a close reading of “Trees” and the poet’s “absolute dependence upon the Supreme Being.”

Literary fashions and aesthetic standards for poetry change — often dramatically so — over time. Today, to be blunt, “Trees” is more the object of parody than a poem judged of lasting merit.

In 1932, Ogden Nash, one of America’s foremost bards of humorous verse, composed “Song of the Open Road” without any explanatory reference. It encompassed just four lines and has been quoted almost as often as its poetic precursor:

I think that I shall never see

A billboard lovely as a tree

Indeed, unless the billboards fall

I’ll never see a tree at all.

In addition, during the past 30 years, the “Alfred Joyce Kilmer Memorial Bad Poetry Contest” has taken place at Kilmer’s alma mater, Columbia University. The evening of competitive doggerel ends with a collective recitation of — what else? — “Trees.”

A century ago, Kilmer’s writing appealed not only to respected critics but also to a wide variety of readers, serious and casual. Strikingly, late in the year when he was killed, a New York publisher came out with a two-volume, hardback collection of Kilmer’s poems, essays and letters — a total of almost 600 pages. In a letter to Father O’Donnell, the editor reported that “the first edition was sold out within three days.” Five more printings followed to meet the demand.

Today Kilmer is remembered less for what he wrote than for being someone who was someone. Many schools in the U.S. bear his name. The Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest in North Carolina was dedicated in 1936 and covers 3,800 heavily wooded acres — a living monument to the composer of “Trees.” There’s also the Joyce Kilmer Park in the Bronx, and even the Joyce Kilmer Service Area on the New Jersey Turnpike, near the writer’s birthplace of New Brunswick.

Perhaps most important, neither his writing nor his military service is forgotten in the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan. His portrait hangs on one wall, and there’s a display devoted to him.

One of the poems Kilmer wrote in France honored a platoon of “Fighting Irish” buried alive during a German artillery barrage. The deadly attack occurred at Rouge Bouquet, and Kilmer used the place for the title of his elegy. “Rouge Bouquet” was read at Kilmer’s graveside in 1918, and it remains regimental tradition to recite the poem at memorial services involving slain comrades.

The poignant lines commemorate heroism on the battlefield, but they also emphasize Kilmer’s adopted Irishness and the Catholic faith he embraced. Near the end, he invokes three of Ireland’s best-known saints and the eternity awaiting the “brave young spirits”:

And Patrick, Brigid, Columkill

Rejoice that in veins of warriors still

The Gael’s blood runs.

And up to Heaven’s doorway floats,

From the wood called Rouge Bouquet,

A delicate cloud of buglenotes

That softly say:

“Farewell!”

Though it’s what critics call an occasional poem, one that is rooted in a specific place for a particular event, the tragic timeliness of “Rouge Bouquet” doesn’t diminish its touching timelessness. Even 100 years later, the poem still resonates as a tribute to wartime sacrifice — and to its courageous, complex creator.

Robert Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Professor Emeritus of American Studies and Journalism at Notre Dame. In his book, Ireland’s Exiled Children (Oxford University Press), he considers Kilmer’s response to the Easter Rising.