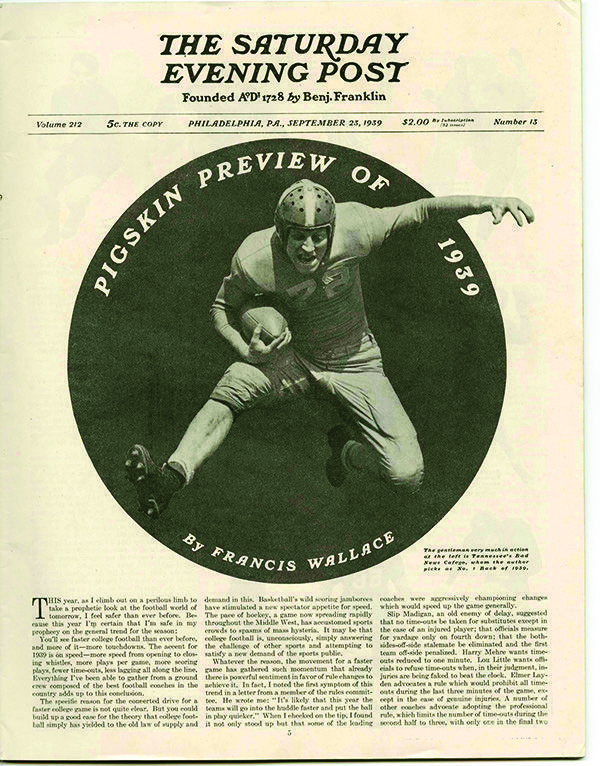

Like a child eagerly awaiting Christmas, Francis Wallace, Class of 1923 and the father of college football’s annual “Pigskin Preview,” was anticipating the release of a magazine carrying his most recent installment in that series. When he saw the issue, it was not the gift he was expecting.

Wallace’s yearly college picks first ran in The Saturday Evening Post in 1937. With the exception of the World War II years of 1943-45, the preview continued to run in the Post each fall through 1948. Wallace was then lured away by Collier’s. When that periodical folded in early 1957, Wallace had to find a new publisher for his now highly anticipated preview.

After the chosen magazine hit the newsstands in autumn 1957, Wallace’s only child, John Wallace ’54, overheard a heated phone conversation between his father and the publisher. For the 1957 installment of the preview, Wallace had selected a periodical then in its fourth year. He had not seen an issue of the magazine but was told its aspirations were akin to Esquire, where notes on men’s fashion ran side-by-side with literary contributions of the highest caliber.

John overheard his father and the publisher going through successive rounds of failed negotiations. While the publisher offered more and more money, Francis wanted to bring an immediate end to his relationship with the magazine, which he felt ran contrary to his Catholic convictions. No compromise was reached. Although Wallace would not write again for the magazine, Hugh Hefner’s Playboy retained the name “Pigskin Preview” and uses it to this day.

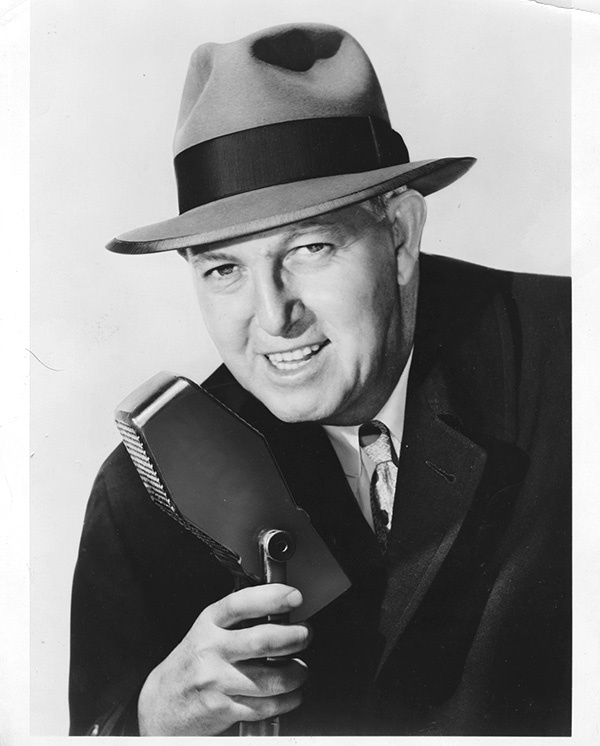

Francis Wallace was much more than the father of the “Pigskin Preview.” He broke the story detailing Knute Rockne’s “Win one for the Gipper” speech; begrudgingly made the nickname “Fighting Irish” stick amongst the press in the Northeast; wrote 17 books as well as screenplays for eight movies based upon his works; and served as a commentator for the CBS television and ABC radio networks. He also was an early voice for reform in college football, and he ran as a Republican candidate for the House of Representatives from his home district in Ohio — he lost but claimed to have received the “intelligent vote.”

John, who now lives in Savannah, Georgia, says his father was not a shy man, and he was comfortable in any setting from New York City to Beverly Hills, California. A large measure of what drove that comfort was Francis’ belief that the stories defining people were tied to the places they lived. Everyone has a story, he thought, and that story could not be separated from a place called home.

While Francis occupied a front row seat at many of the greatest sporting events of his time, John says he most enjoyed talking with people in his own hometown of Bellaire, Ohio. In particular, he liked sitting outside the police station and engaging in “bull sessions” with officers serving a community defined by the rhythms of coalmining and steel production. The officers loved hearing the latest tales from one of the greatest sportswriters, says his son, and Francis loved hearing about the routine events of their day.

In a strange twist of how history is recorded, Wallace’s legacy is now almost forgotten. At the time of this writing, not even a Wikipedia page — one arbiter of acclaim — bore his name. But a look back at one of Our Lady’s most loyal sons offers some eye-opening views on past and present issues of college football.

John Francis Wallace (1894-1977) was the son of Irish immigrants John Simon Wallace (1848-1917) and Mary Griffin Wallace (1856-1932), who claimed Bellaire as home in 1871. Just across the river from Wheeling, West Virginia, Bellaire nurtured a wealth of industries including “coal, steel, glass, enamel, railroads and electric power.” Describing his hometown, Wallace noted, “You can see the town from the circling hills — on a clear day. But that’s pay-dirt, brother. When Bellaire is clean it doesn’t eat.”

Perhaps only football fostered a deeper love among the people of Bellaire than the industries that put food on their tables. Young Wallace went to St. John Central, which had its days, along with Bellaire High School, as a football power. As he says in his 1951 book Dementia Pigskin, the Ohio community of approximately 15,000 turned out “more than one hundred players and twenty coaches for fifty colleges” from the mid-1920s through the early 1950s. Wallace was born into this culture of coal, steel and football. As an adult, beyond taking up residence for short seasons in New York and California, Wallace and his wife, Mary Heath Wallace (a teacher and principal at St. John’s Grade School), proudly immersed themselves in that culture almost all of their days.

After high school, Francis worked in the mill for the Wheeling Steel Corporation. But his seven siblings conferred behind his back and, says his son, concluded, “This guy is pretty smart — let’s get him a boost.” They pooled their resources in an effort to financially support their brother as he headed off in 1919 to Notre Dame, a campus revered by his mother and father.

That October, freshman Wallace was waiting with some other first-year ND students for the Hill Street trolley when coach Knute Rockne, known in the community to pick up hitchhikers, offered a ride to the young men. As Wallace wrote in his 1960 book Knute Rockne, football practice apparently had not gone well that day, and the boys sat rigidly in the back seat, “feeling the explosive power of the man up front, ready to roar at the first spark.”

Wallace and Rockne would not meet again until the following September. Wallace, now having exhausted his financial resources, “brashly” came to the University president, Rev. James A. Burns, CSC, to plead his case. That same day, Rockne came to plead a case for his star player, George Gipp, who, Wallace later wrote, “had bet he could absent himself from more than the permissible number of classes in the law school. He had lost, been declared ineligible for athletics.”

Father Burns met both Wallace’s and Rockne’s pleas. Gipp was to be reinstated, but only if he could pass “an oral examination now without a chance for cramming — and let his performance decide.” Of course, “Gipp, always at his best under fire, came through.” Then, according to Wallace, Burns “practically created a job that was to put me in the newspaper business.” Within three months, he says, “I would be writing the story of George Gipp’s funeral; and within six months would be working for Rockne.” His career as Rockne’s press intern and as a writer was launched.

“I did not then realize that I was to be a camera in the tail of the Rockne comet that would blaze gloriously through the national sky for the next decade,” Wallace wrote in his biography of Rockne. The student’s job at Notre Dame was to work with Rockne on identifying critical details for public consumption concerning the team, prepping those details and channeling them to the proper media outlets.

Perhaps more important than the experience that came with learning to package stories and getting them to the right people was an attitude Wallace and the other student sportswriters absorbed in the presence of their mentor. As Wallace wrote, Rockne “either recognized budding talent, or infected us, as he did his players, with that feverish desire to be best.”

Before taking that desire to New York City in the summer of 1923, thus making the Irish a regular presence in that city’s dailies, Wallace also had earned the acclaim of his peers for his efforts. Under his yearbook photo in the 1923 edition of The Dome are the words: “No other journalist at Notre Dame has had more bylines in the newspapers and magazines than Frank, Sports Writer and Columnist. . . . Frank has handled Notre Dame sports for the nation.”

It was a calling he continued to follow throughout his professional life. In a few short weeks Wallace went from serving as the student publicity director for Rockne to being the night city editor for the Associated Press, but his talent and interests soon led him to where he truly belonged — covering sports for the New York Post and then for the New York Daily News.

On Monday, November 12, 1928, five years after Wallace left South Bend, the Daily News published the story for which he may be most remembered: “Gipp’s Ghost Beats Army.” The previous Saturday, the Irish had played against a heavily favored Army team before a sell-out crowd at Yankee Stadium. When the series was launched 15 years earlier with a game highlighting the passing exploits of Gus Dorais and Knute Rockne, the teams played on the West Point campus at Cullum Hall Field. No admission was charged and “the knock-down circus-seat bleachers were almost completely filled by 3,000 spectators, a number that exceeded all expectations for the occasion.”

Most Irish fans likely know the outcome of the 1928 game. Although the Cadets wound up on the losing end, even Stuart Miller, a “fourth-generation Brooklynite” and writer for the Sporting News, included it as the 28th greatest day in his 100 Greatest Days in New York Sports (no doubt a less-biased writer would at least place it in the top 10). After being tied 0-0 at halftime, Notre Dame willed its way to a 12-6 victory.

According to Wallace, Rockne pulled out a speech at halftime that he had saved for eight years, honoring George Gipp’s supposed deathbed wish to implore the team at some point “to go in there with all they’ve got and win just one for the Gipper.” For a host of reasons, including doubters who ask why Rockne would wait years after Gipp’s death to honor his request, that speech is much debated and will give historians ongoing fodder for decades. Regardless, the truth of a great story resides somewhere between its motivational power and its historical veracity — thus the plaque on the wall in the football locker room on campus in South Bend that bears those words to this day.

Another impact Wallace had on the lore defining his alma mater’s football program was the way he helped canonize the University’s team name of the “Fighting Irish” among sportswriters in the Northeast. In an age of discrimination against Catholics and the ethnic groups from which large numbers of the faithful were drawn, a nickname such as the “Fighting Irish” harbored connotations worthy of resistance.

In Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football, Murray Sperber says Wallace objected when his fellow sportswriters in the Northeast would refer to Notre Dame’s football team as the “Rambling Irish,” “Rockne’s Rovers,” the “Wandering Irish” or “Rockne’s Ramblers.” Wallace, writes Sperber, found these names “pejorative, implying that the Catholic school was a ‘football factory’ and that its players were always on the road, never in class.”

Wallace’s initial response was to “create an acceptable alternative — nonethnic and nonnomadic — and [he] came up with the ‘Blue Comets,’ based on the team’s blue uniforms and quick offense.” Like most artificially imposed nicknames, Sperber notes, Wallace’s efforts failed. In 1925, while working at the New York Post, Wallace apparently accepted defeat and began to consistently refer to the sons of his alma mater as the “Fighting Irish.” When Wallace moved to the New York Daily News in 1927, he continued the practice and compelled the wire services to begin doing the same. Later that year, writes Sperber, when asked by Herbert Bayard Swope of the New York World about Notre Dame’s official position on the rising popularity of its nickname, Father Matthew J. Walsh, CSC, then the University’s president, “decided to put the school’s imprimatur on ʻFighting Irish.ʼ”

Wallace’s early efforts as a sportswriter were not limited to contributions he made to his alma mater. While he covered a variety of sports for the Post and the Daily News, his study of philosophy and his Catholic faith compelled him also to focus on the broader questions surrounding collegiate athletics. To Wallace, the root challenge facing college athletics in his day — a prescient look at an issue not that different from the one facing college athletics today — was money.

One of the first articles Wallace published concerning the need for reform in college athletics ran in the November 1927 issue of Scribner’s. He wrote “The Hypocrisy of Football Reform” in response to a proposed code of ethics offered by what was called the Committee of 60. The code’s major point was that scholarships and loans should not be awarded to students on the basis of athletic skill.

Wallace contended that the only realistic and honorable course of action was to “state the principle that as long as a boy is a legitimate student it is nobody’s business how he pays his college expenses — especially as this is the exact position of the colleges in respect to all students who are not varsity athletes.” In essence, Wallace thought a moral issue was at stake. While colleges and universities were generating considerable revenue under the guise of amateur athletics, those amateur athletes were not allowed to pay for a college education with their football talent.

A quarter of a century later, in his correspondence with Walter Byers, the founding executive director of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, Wallace began a pitch for subsidies. He suggested “tying a fixed rate of pay to the time a boy spends in practicing for and playing in college athletics.” Byers, however, firmly objected to this resolution.

One can speculate as to what Wallace might think of college football today. He would likely abhor confirmed practices such as the phantom or paper classes in which athletes at the University of North Carolina were enrolled and allegations that Florida State University football players received preferential treatment from Tallahassee law enforcement officials. However, he would no doubt equally dislike how the economics of the game are structured, including who financially benefits the most and who benefits the least.

Wallace himself was one who definitely benefited from the game of college football, particularly through his newspaper work and the “Pigskin Preview.” His books were generally sports-related fiction. His first book, Huddle!, was published in 1930 — a story loosely based upon Knute Rockne and the Fighting Irish. He went on to publish a host of football-related books — O’Reilly of Notre Dame and Stadium in 1931, That’s My Boy in 1932 and Big Game in 1936. He also somewhat broke the mold in 1936 by publishing Kid Galahad, a tale of an upstart boxer. John Wallace says his father was likely most proud of Explosion — a 1943 work that reflected upon the fears plaguing people in coal-country communities such as Bellaire. Francis Wallace’s own father had labored in those mines.

Wallace converted several of those books and a number of his short stories into screenplays for motion pictures. Touchdown was released in 1931, Huddle and That’s My Boy in 1932, The Big Game and Rose Bowl in 1936, Kid Galahad in 1937 (and again in 1962) and, finally, The Wagons Roll at Night in 1941. Of equal note are the actors and actresses who found their way into films based upon Wallace’s work. For example, Huddle starred Ramon Navarro and The Wagons Roll at Night starred Humphrey Bogart. The 1937 release of Kid Galahad starred Edward G. Robinson and Bette Davis while the 1962 release featured Elvis Presley.

Perhaps no labor was of greater love for Wallace, however, than efforts he expended on behalf of his alma mater. Wallace was elected president of the Notre Dame Alumni Association in 1949 and also served on the Library Council and as the inaugural chair of the Sports and Games Collection (now the Joyce Sports Research Collection). His last three books — Knute Rockne (1960), Notre Dame: From Rockne to Parseghian (1965) and Notre Dame: Its People and Its Legends (1969) — all found their inspiration in the shadow of the Dome.

Knute Rockne was not only a touching tribute to his mentor but also Wallace’s calculated effort to right inaccuracies perpetuated by the fleet of ill-conceived biographies rushed to market after Rockne’s tragic death. Perhaps the most comprehensive way Wallace captured his love for his alma mater, however, was through the dedication of his last book to Reverend Theodore Martin Hesburgh, CSC, “Who Caught the Pass from Sorin.”

Todd C. Ream is a professor of higher education at Taylor University and a research fellow with Baylor University’s Institute for Studies of Religion. Most recently, he is the author (along with Perry L. Glanzer) of The Idea of a Christian College: A Reexamination for Today’s University. He and his family live in Greentown, Indiana.