I didn’t set out to learn about Thomas P. Bulla. Rather, my search was inspired by The Underground Railroad, Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, which tells the story of teenage Cora and her bold escape from slavery. Detailed and brutal in its depiction of plantation life, Whitehead’s novel turns to fancy as it forges a literal subterranean locomotive connecting stops along Cora’s route north from Georgia. A gruesome Gulliver’s Travels, the foreboding narrative offers different possibilities for the future of black-white relationships in America at each stop of her journey, slave-catchers in vicious pursuit. Near the book’s ambiguous conclusion, the reader comes up for air as Cora spends time in a black utopian farming community in Indiana.

In the following days, when I was still living with the characters and imagining their lives continuing beyond the edges of the novel’s final pages, I began researching the history of the Underground Railroad. Historian Eric Foner estimates that the loosely woven network of blacks, whites and Native Americans, from all levels of society, aided more than 1,000 freedom-seeking slaves per year between 1830 and 1860. It was focusing on Indiana, then South Bend and, finally, Notre Dame that I came upon Bulla, whose obituary in the December 1, 1886, South Bend Tribune lauded him as one who “did, perhaps, more than any other one man in the earlier history of the county to advance its interests and prosperity.” Bulla, a friendly neighbor to Father Edward Sorin and the priest’s frontier school, was a pioneer, farmer, schoolteacher, surveyor and “earnest abolitionist.” And he may well have been an Underground Railroad stationmaster.

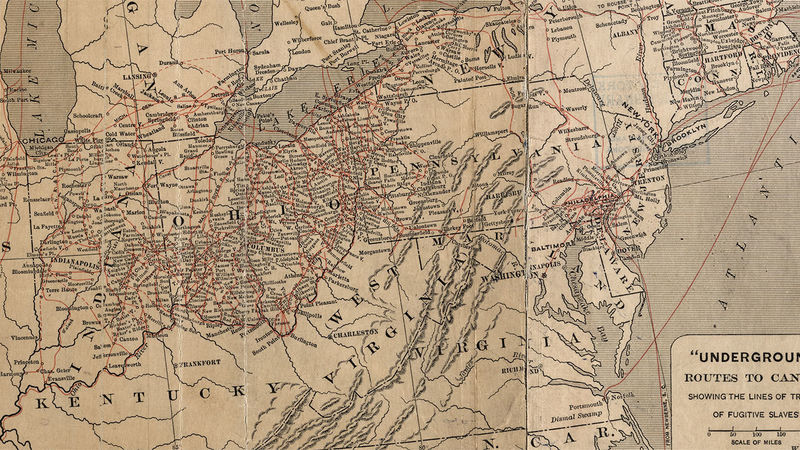

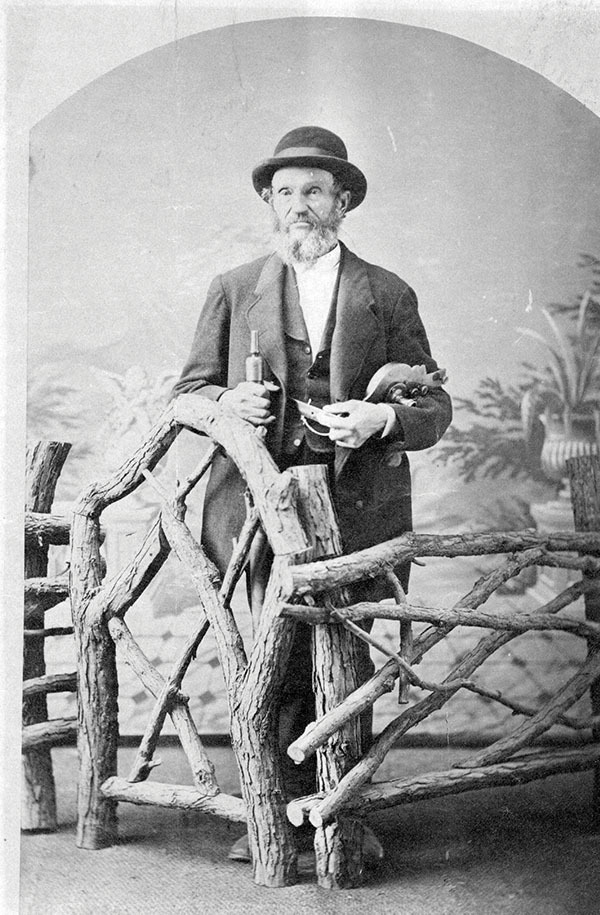

The slave trade kept abolitionists like Thomas Bulla dodging the law as they maintained the Underground Railroad, photo courtesy of The History Museum, 1898 map of routes marked in red courtesy of New York Public Library Archives.

The slave trade kept abolitionists like Thomas Bulla dodging the law as they maintained the Underground Railroad, photo courtesy of The History Museum, 1898 map of routes marked in red courtesy of New York Public Library Archives.

My own journey began — as it often does these days — with a Google search. To my surprise, “Notre Dame AND Underground Railroad” returned a series of websites — including one that offered photographs of a campus building referred to as the “Bulla Farmhouse” and described as an “Underground Railroad station.”

The edifice in the photo sure looked like a Notre Dame building — those telltale tawny bricks handmade from the marl of the campus lakes. It even looked like a building from my workday commute — now named the Wilson Commons and located at the southwest corner of the Fischer O’Hara-Grace graduate student residences.

To my untrained eye, the building looks, well, old, now out of place among the O’Hara-Grace apartments, the newer Fischer apartments and the still newer McCourtney Hall. The relative wildness of this patch of property on the edge of campus offers up the building as a playground for the moral imagination. Could this building really be an antebellum Underground Railroad site?

On a mild winter morning in December, I set out to find the answer. University archivist Peter Lysy and architect Tony Polotto from Notre Dame Facilities joined me to play This Old House on a visit to the Wilson Commons, with Fischer O’Hara-Grace rector Nathan Elliot ’99 as our host.

Walking hallways slightly too narrow and descending stairways slightly too steep, our team gathered in the musty basement of the building currently used as a community center for Notre Dame graduate students. Sliding away the ceiling tiles, Lysy used his flashlight to illuminate modern tongue-and-groove floor boards, with joists and other framing lumber planed smooth on all four sides in the modern way. Meanwhile, Polotto directed our attention to the basement walls, clearly made of concrete blocks, rather than the pargeted lime or fieldstone walls of other 19th century foundations on campus. These post-bellum construction techniques matched the steel lintels, rather than brick or stone, over the structure’s exterior windows and doors.

As we emerged from the dark basement, it was clear to our team that the Internet claims were wrong: Wilson Commons is not an Underground Railroad site. In fact, a search of the University’s registry of buildings on campus estimates its construction date as 1920. However, our inspection did not answer the question of how this building mistakenly came to be referred to as the “Bulla Farmhouse.” Who was Bulla, and why would people associate him with the Underground Railroad? If this wasn’t his farmhouse, where was it?

At the University Archives on the sixth floor of the Hesburgh Library, Lysy produced decades of plat maps and surveys showing land ownership around the University. Father Sorin’s growing vision for Notre Dame could be seen as his name appeared in more and more squares on the chess board. He bought property contiguous to Notre Dame’s campus but also properties farther afield that could be traded or sold to finance Notre Dame’s growth.

One piece of land, in particular, resisted Sorin’s strategy: the property at the northeast corner of the original campus. This parcel proudly displayed one name on the plats from 1832 all the way until the 1920s. That name was Thomas P. Bulla. Bulla family history says the property was transferred directly to Bulla by a land grant signed by President Andrew Jackson. In the earliest aerial photographs of campus, a grove of trees shades a rectangular sliver of that Bulla property — the kind of grove that would protect a farmhouse from the vicissitudes of weather on the Indiana prairie in the early 19th century, and from the invasive gaze of flying cameras in the early 20th.

Lysy sent me home with Father Arthur Hope’s 1943 history of the University, Notre Dame: One Hundred Years. After recounting Sorin’s arduous journey from France to New York to Vincennes to Notre Dame, the Holy Cross priest writes: “In the vicinity of the University there was a household that cared for the negro slaves making a dash for Canada and liberty (the old Bulla house, on the Eddy Street road, directly across from the present Biology Building and recently demolished), and you may be sure that Father Sorin’s long nose had, for months, detected what was going on there.”

I realized then that the owner of that demolished household — about where Flanner and Grace halls stand today — held the secrets I was after.

On a cold Saturday in March, I went looking for Bulla at the St. Joseph County Public Library and rolled through spools of microfilm and dug through dusty files of yellowing clippings. Obituaries, newspaper articles and editorials, autobiographical sketches, local histories written in the 19th century, and nearly illegible census and other handwritten records allowed me to reach back into time and uncover what had faded from view.

- God, Country, Notre Dame et cetera

- 175 and Counting

- En Route

- The Passing of Ancestral Lands

- The Stationmaster

- The Littlest Domers

- The original home-grown do-it-yourself meal plan

- Gettysburg, 1863

- Washington Hall

- Commencements through history

- Cartier Athletic Field

- The old ND&W

- As ND as football, Mother’s Day and community service

- Notre Dame vs. Army: The rivalry that shaped college football

- Bound volumes, illicit lit

- Mock political conventions

- The Collegiate Jazz Festival

- When the Irish got their fight back

- The damnedest experience we ever had

- 40291

- It takes a University Village

South Bend’s Center for History provided more pieces of the Bulla family puzzle among the photographs, family documents and personal effects archived there. My research revealed that the Bulla family had its own unique migration story, but one that was part of massive migration patterns defined by nationality, race and religion.

The Bullas were Quakers who emigrated from Ireland, taking up residence in Lancaster and Chester counties in Pennsylvania, where they were among the early settlers in a state founded by another Quaker, William Penn. Thomas Bulla’s father, William, was born in 1770 in Chester County, though the family moved to Guilford County, North Carolina, in 1791. Guilford was a strong Quaker enclave, populated by the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road that brought many Pennsylvanians to the piedmont counties of the Carolinas.

By the late 18th century, Quaker theology of the “inward light” and Christ’s presence within each and all led most members of the Religious Society of Friends to reject slavery. This light illuminated the Gospel command to “love your neighbor as yourself.” North Carolina laws severely restricting manumission — the act of an owner freeing his slaves — left many Quakers who wished to abandon the “peculiar institution” few options other than leaving the state.

William Bulla, his bride and two daughters joined this Quaker migration to the free states of the Midwest, living for a short time near Dayton, Ohio, where Thomas P. Bulla was born in 1804, before continuing on another 40 miles to Richmond, Indiana, the edge of the frontier for European Americans. Quakers referred to their new home as “the promised land.”

Though Thomas Bulla lived a spartan life on the frontier, he gained sufficient education to become a teacher himself. In the early 1820s, Bulla taught school in the same log cabin where he himself was once a student, with windows covered with oiled paper rather than glass. Bulla, who would rely upon his talents as a teacher for income later in his life in Clay Township, adjacent to South Bend, had among his pupils in Richmond the young George Washington Julian, who served six terms in Congress and was a leading opponent of slavery, a founder of the Free Soil party and later the Republican Party, and a supporter of the 13th amendment that abolished slavery in 1865.

Bulla’s community in Wayne County was deeply abolitionist. Levi Coffin, who would later be heralded as the “President of the Underground Railroad” was a prominent member of the Quaker community. Richmond, located just 50 miles from the Ohio River, which formed the border between the southern slave states and the putatively free north was a “stopping place for runaway slaves.” It was here that, according to his obituary, “the young Bulla became a very enthusiastic abolitionist.” No doubt his enthusiasm was fueled by the witness of his father, William, and the specific actions he took on behalf of neighbor and “his fealty to the principles of human liberty.”

In 1823, William and his fellow Quaker and father-in-law, Andrew Hoover, aided the escape of a black man living under the name of “George Shelton,” whom slave catchers accused of fleeing from his Kentucky master in 1821. Shelton had been living as a free man and working in the porous border area, where Hoosiers both for and against slavery could be found. William Bulla and Hoover reportedly helped Shelton escape from the slave catchers through a window as Bulla “caught the catcher by the back of the neck and threw him across the room.”

For that act of humane liberation, a judge ordered William Bulla to pay the slave owner more than $1,000 for the slave and associated costs. With land at $2 an acre, this was a towering sum and a potentially ruinous penalty. Quaker neighbors stood in solidarity with Bulla and raised about $200, but this still left William, his wife and 10 children deep in debt. One of those children, David, recalled their father’s witness: “And one day while my father was in abstract thought on his misfortune, a dove alighted on his head, a short time, then passed out at another door, and some regarded this as a testimonial of approval for what he had done in the rescue of one man from servile bondage.”

William’s actions, which grew out of his Quaker beliefs, led him to answer the question of “Who is my neighbor?” in a way that affected his oldest son, Thomas, for the rest of his life.

In October 1832, Thomas Bulla left Richmond and, arriving in South Bend, purchased 160 acres in Clay Township. His land adjoined the property owned by Stephen Badin, the first Catholic priest ordained in the United States, whose mission cabin Sorin would eventually inherit for his school.

Bulla had visited the area on multiple occasions before, perhaps as early as 1824. When his labor was not needed for his father’s harvest, the young Bulla’s extraordinary thirst for knowledge and experience in this “new country” led him to take work as a millwright and carpenter in Niles, Michigan; a rail splitter near Fort Wayne, Indiana; a teacher, wheat cutter and furniture maker near Peoria, Illinois; a riverboat worker in St. Louis; a road grader in Detroit. He even crossed the Detroit River into Canada so that he could say he had “been in the domain of George IV.” Bulla was resourceful and confident in his skills; he was not afraid to take risks.

By the spring of 1833, almost a decade before Sorin’s arrival, Bulla had erected the first hewn log house in Clay Township. Bulla recalls that his “neighbors regarded it as a rather aristocratic structure,” with its “hard-wood floor of matched oak, a brick chimney and pine shingle roof.” Other accounts refer to the cabin as “quite a pretentious one at the time” consisting of a large room serving as kitchen, dining room, bedroom, with a winding staircase leading to a garret. According to Bulla’s son William, the garret stored “sundry jars of preserves and other delicacies — in readiness for company and away from the poking eyes (and fingers, too) of the children.” It is revealing that William would recall this space as a “hiding place” stowing away food for visitors.

Although Bulla remained a farmer all his life, he was appointed county surveyor in 1836, a position he held for 20 years. Many of the early surveys in the county bear Bulla’s name; major developers and landowners hired Bulla to draw their holdings. So Bulla’s name was well-known in the county when 10,955 people were counted in the 1850 census, and he knew well the county’s nooks and crannies — from the hills of Potato Creek where the county’s first African-American community was formed to the northerly crossings over the St. Joseph River that led to Michigan and freedom.

Bulla’s public life is well-documented, and his strong stances on matters of moral principle — including slavery, which he called a “great national evil” — were also well known locally. In 1880, six years before his death, the 76-year-old Bulla wrote, “My sympathies ever were against oppression of every kind, physical and mental. I have lived to witness the removal of one of the darkest stains on our character as a nation.” Though Bulla describes himself as a “witness” to the fight against slavery, other documents speak of his actions.

In a cardboard box in South Bend’s Center for History, I found a handwritten biographical sketch that Bulla’s son, William, wrote in 1900 about his father. Thomas Bulla, wrote his son, “maintained the habit of reading and study throughout his whole life,” including the “speeches and writings” of noted abolitionists such as Thomas Clarkson, Elijah Parish Lovejoy, John P. Hale, Wendell Phillips and William Lloyd Garrison. He also subscribed to the anti-slavery weekly, The National Era. William Bulla recalls that, as a young boy, he would borrow his father’s copy to read the weekly installments of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was originally published serially in that national newspaper in 1851-52.

William writes that his father was so “imbued with the spirit of civil liberty and believing in the equality of all men in their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, he could not reconcile the theory of a free government in which the traffic in the bodies and souls of men was permitted and protected.” William also comments that his father and an uncle were for years, “the only voters of Clay township casting their ballots with the anti-slavery or free-soil party.”

But the biographical sketch also suggests that Bulla’s anti-slavery position moved him to action. William writes, “Particularly after the enactment of the infamous ‘fugitive slave law’ he was ever the friend of the escaping colored man who might be on his way to Canada and freedom, rendering such assistance as was in his power to do — whether in affording assistance to an escaping fugitive or refusing to play the part of a blood-hound in aiding in his capture.”

Bulla’s active resistance to the Fugitive Slave Law can also be found in the Hesburgh Library — in an essay, “The Underground Railroad in Northern Indiana,” typewritten in 1939 by Helen Hibberd Windle and based on interviews by Esse B. Dakin in 1899: “Mr. Thomas H. Bulla, son of Thomas P. Bulla, remembers distinctly an incident of the Underground Railroad which occurred about 1856. One evening in early autumn a knock came on the door as the family sat at supper in the Bulla farmhouse in Clay township and upon opening the door a man asked Mr. Bulla to step outside a moment. Young Tom, aged, eight, followed closed by his father’s side and saw a wagon standing there with the usual wagon box covered by another wagon box turned upsidedown. In this space were two negroes who were being carried northward. The man in charge had stopped for food and rest. An abundance of food was gathered by Mr. Bulla and placed in the wagon and the party proceeded on its lonely dark drive toward freedom.”

Even though Bulla’s obituary identified him as a “very enthusiastic abolitionist” and an “earnest abolitionist,” Bulla was necessarily discreet about his role with the Underground Railroad. Beyond humility, he had good reason to remain silent.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, signed into law by President George Washington, reinforced the Constitution’s requirement that escaped slaves be “delivered up” to their owners. The law imposed a $500 penalty on people like Bulla who would “obstruct” or “hinder” or “rescue” fugitive slaves — a fine that was in addition to legal liability for the cost of the liberated slave.

Personal liberty laws, the uneven application of the act in some northern states and Supreme Court decisions led to the even more draconian Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This version imposed jail time and doubled the penalties on people like Bulla, and required citizens to aid in the capture of fugitive slaves.

While Bulla and others, in theology and in practice, decided that their neighbors included blacks and that neighborliness required acts of solidarity, the State of Indiana doubled down, passing laws to exclude blacks and to punish those who assisted in their finding freedom. Though Indiana had outlawed slavery in its founding Constitution of 1816, a constitutional convention leading to the superseding constitution of 1851 revealed ugly sentiments in Indiana. Fugitive slaves and free blacks alike were referred to as “aliens and enemies” and one delegate to the convention called for “preventing our State from being overrun with these vermin.”

The resulting Indiana Constitution of 1851 went beyond the extreme federal law, declaring, “No negro or mulatto shall come into or settle in the State” and making it illegal to employ newly arriving free blacks or to encourage them to stay. Fines for breaking these provisions were to be collected for the colonization in Africa of blacks living in Indiana. In effect, Indiana sought to build a virtual wall to keep out nearly one-fifth of the country’s population. This affected lives across Indiana’s borders and revealed Indiana to be a state where freedom had a fuzzy and unstable meaning for blacks in the decades preceding the Civil War, just as Whitehead’s Cora experienced in his Underground Railroad.

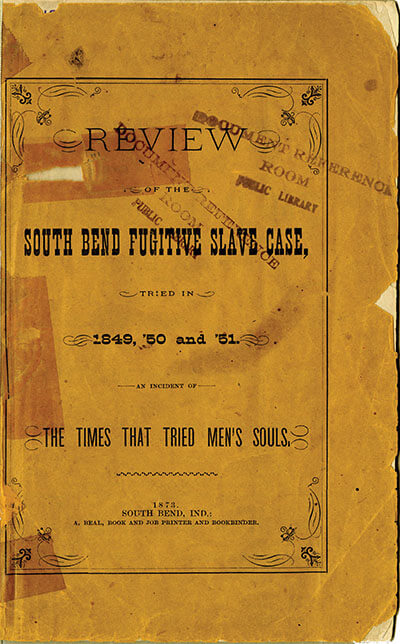

The “South Bend Fugitive Slave Case” of 1849 offers a singular perspective through which neighborliness and solidarity among abolitionists and others collide with the efforts of those enforcing both slavery and the law. The Saint Joseph Valley Register described the incident that led to the court case as an issue of “life and death” that “caused so much excitement in our usually quiet town.”

The Fugitive Slave Case became a notorious example of the conflicts between morality and legality facing South Bend and the nation.

The Fugitive Slave Case became a notorious example of the conflicts between morality and legality facing South Bend and the nation.

It began — according to a pamphlet published in 1851 at the “Anti-Slavery Office” in New York and a 1985 article by an Indiana University historian — on the night of September 27, 1849. Lucy Powell, three of her sons — George, James and Lewis — and Lewis’ wife lay in their beds near Cassopolis, Michigan, about 20 miles north of South Bend. It was harvest season; their limbs were sore and overworked — but free — as they rested after another day of picking sweet corn.

Lucy’s husband, David, and their son Samuel were out for the evening, but she was awakened by voices that she recognized — John Norris, their former master, and his band of slave catchers. The Powells had labored in bondage for Norris on his horse farm in Boone County, Kentucky, until October 1847. That is when the Powell family escaped from slavery by crossing the Ohio River into the temporary safety of Indiana, on their way to Cass County, Michigan. The area was settled largely by Quakers, some of whom, like the Bulla family, had come north to live outside of the confines of slave society. For two years the Powells lived in freedom with as many as 1,500 other free blacks and former slaves between Cassopolis and Vandalia, Michigan. Described by their neighbor as “quiet and industrious persons,” the Powells had purchased land and “were working hard to pay for it.”

Norris and his gang of eight men forcibly broke into the Powells’ home with pistols and bowie knives drawn, bound Lucy and her sons with cords, hid them in their covered wagons and set off south for Kentucky, where Norris would once again force them to live as his property.

As the wagons and their human cargo rolled south through the night, Wright Maudlin, described as a white friend and neighbor of the Powells, raced on horseback to find a lawyer to assist the Powells. The description of Maudlin as simply a neighbor of the Powell’s is not quite accurate. My research, assisted by the Underground Railroad Society of Cass County, Michigan, shows that Maudlin was actually a well-known Quaker agent on the Underground Railroad, who frequently entered Kentucky to assist fugitives on their way north to freedom. Tellingly, Maudlin was born among the Quakers of North Guilford, Carolina, where Bulla’s father was raised.

Maudlin must have known that Mr. Edwin B. Crocker, Esq. of South Bend would be receptive. By morning, Crocker petitioned the Honorable Elisha Egbert, probate judge of Saint Joseph County, for a writ of habeas corpus. Judge Egbert issued the writ, and a deputy sheriff and group of citizens from South Bend set off to serve the writ on the kidnappers and their captives, whom they found a mile south of town. Surrounded by “thirty or forty” citizens from South Bend, Norris relented, and the Powells were brought to South Bend for a determination of their legal status.

Norris was represented by Jonathan A. Liston, a prominent South Bend attorney. It is no coincidence that the slave owner would seek Liston’s services. A local history recounts Liston yelling “with bitter violence” at Almond Bugbee, a local abolitionist who spoke out in defense of other men arrested for violating the fugitive slave law: “You are a traitor, a traitor to your country.”

After hurried legal proceedings in which each side had but hours to submit written pleadings and prepare oral arguments, Judge Egbert ordered the Powells to be freed. His reasoning seems to have been that Norris did not obtain a certificate for recapturing his slaves that Egbert deemed a requirement under the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act.

As the verdict was announced on Friday night, Norris and his Kentuckians seized the Powells and, weapons drawn, threatened to kill anyone who interfered. In the excitement, attorney Liston climbed on top of a table and shouted to his clients, “Gentlemen, protect your property! The first man that touches your property, blow them through!”

When Egbert regained control of the courtroom, it became clear that Norris had obtained his own writ under an 1824 Indiana law meant to help slaveholders recapture their fugitive slaves. The Powells would be held in jail for the weekend until a Monday morning hearing to determine their fate.

Over the weekend, scores if not hundreds of members of the Powells’ community — most black, but some white — arrived in South Bend to support their neighbors. Census records indicate only 39 blacks lived in all of Saint Joseph County in 1850; the sight of hundreds of free blacks in the streets of South Bend would have been alarming to the Kentucky slave owner.

Norris, seeing the growing crowds and sensing what the newspaper referred to as “the strong feeling of sympathy for the oppressed evidenced by our citizens” did not show up for his hearing on Monday morning. Instead, on Liston’s suggestion, he set a new course, pursuing suits for recompense and damages in the federal courts against the South Bend residents who impeded his kidnapping of the Powells.

The anti-slavery pamphlet, most likely written by Crocker himself, recalls the Powells’ release from jail: “The colored friends and neighbors of the captives immediately came forward, conducted them out of the court-house to a wagon, and quietly rode off with them. On the bridge adjacent to town, they halted, and made the welkin ring with their cheers for liberty. They rode off, singing the songs of freedom, rejoicing over the fortunate escape of their friends from the horrible fate of slavery. Thus ended one of the most exciting scenes ever witnessed in Northern Indiana.”

Lucy and David Powell appear in the 1850 federal census records, living with their 14-year-old son, James, in Porter Township in Cass County, Michigan. Wright Maudlin and his family of seven are listed as neighbors. By the 1860 census, however, the Powells’ names disappear. Having risked everything for freedom in a way that even their most ardent white well-wishers would never have to, perhaps the Powells sought a more secure end to their freedom journey in Canada.

Norris would successfully sue nearly a dozen residents of South Bend — including the Powells’ lawyer, the deputy sheriff and others who surrounded Norris as he passed through South Bend — for the cost of his human property and for obstructing his attempt to recover it. The defendants hardly stood a chance; both federal law and politics favored the slave owner.

The case was heard in Indianapolis by Supreme Court Justice John McLean, who was riding circuit. McLean, who at that time was considering a run for the presidency, gave highly charged instructions to the jury in the presence of the governor of Indiana and the governor of Kentucky. Insisting in the midst of growing tension between the South and the North “that every cord which binds us together should be strengthened,” McLean appealed to the concept of “neighbor.” However, the neighbor McLean had in mind was the slaveholder, not those fleeing bondage. He informed the jury that a person who actively assisted fugitives violates the law “to the injury of his neighbor” and is an “enemy to the best interests of his country.”

The abolitionists of South Bend who acted on conscience would pay a steep price for their actions; some were ruined financially. Some were able to stretch the cases out for years through transferring their property to family members to avoid collection, though many of these sales eventually were overturned. At other times, residents of South Bend stood in solidarity with the defendants by refusing to bid on their property when it was auctioned off to satisfy debts owed to Norris.

Bulla knew most, if not all, of the defendants in the South Bend Fugitive Slave Case; the local abolitionist community was small. An 1880 history of the county describes the intimacy of these neighbors in conscience as a “little band of nine men in South Bend, who, in those early days, braved public odium and reproach for conscience’ sake.” This band also included the spouses and family members whose secret mercies did not find print in the written histories of South Bend. While white abolitionists had access to the press and to the courts, free blacks in South Bend such as James Washington and a “Mr. Sawyer” risked life and liberty as solicitors and conductors for the Underground Railroad. Their stories, and the story of how they worked together with their white counterparts in a northern state where the constitution was even hostile to the presence of blacks is the kind of “local research by local people” that remains to be written, according to historian Eric Foner.

Thomas Bulla and Father Sorin would be neighbors throughout their lives, though the historical record reveals only glimpses of their 44-year friendship. A Bulla family history recalls the 1842 arrival of “Father Sorin and his band of brothers” to “the lands purchased by Fr. Badin” making Bulla “the nearest neighbor to the site of the proposed institution of Notre Dame.” In his log cabin schoolhouse, Bulla taught the young Alexis Coquillard, the nephew of the county’s earliest European residents. It would be Alexis, “then a gangling youth of seventeen,” who would lead Sorin from South Bend to Badin’s abandoned and more modest log cabin on the edge of Saint Mary’s Lake.

Alexis would soon become one of Notre Dame’s first students, and Bulla would leave a request in his private papers that Alexis serve as one of his pallbearers (a request with which he complied, along with other students Bulla taught in the county’s first school). A weathered and chipped chest-high marble obelisk gravestone marks Bulla’s burial site at South Bend’s City Cemetery.

Though I have found no evidence of Sorin or Bulla writing about the other directly, records suggest a cordial and more than casual relationship. Old issues of the student-run Notre Dame Scholastic magazine mention “our kind neighbor, Mr. Bulla,” pulling a 35-inch gar pike from Saint Joseph’s Lake, and the Bullas and their adult children being “well known and esteemed neighbors” who opened their home during “our great calamity” — the fire that destroyed much of the University on April 23, 1879. University records indicate financial ties between the Bullas and Notre Dame; perhaps the Bullas sold crops to the University to feed its growing student population or even Mrs. Bulla’s woven linen shirts, made from flax grown on their property, to keep the students clothed.

Another source speaks of Sorin and Bulla engaging in earnest, respectful conversations: “The friendly calls between these two men were quite frequent, in which the differences of their respective views on religious matters were freely discussed.” Bulla was not a Catholic; his own religious journey spanned a Quaker upbringing to becoming an elder of the Disciples of Christ, also known as the Christian Church. Bulla would, however, send his sons to Notre Dame — evidence of the University’s ecumenical origins. “As time passed,” it was later written of the Sorin-Bulla visits, “these calls became less frequent, though neighborly friendship existed so long as both lived.”

When Bulla died in his South Bend home on December 1, 1886, Scholastic reported the death and extended sympathy to his sons, Milton, class of 1865, and Thomas, class of 1867: “He was well known and respected as a good man and citizen, and his demise is mourned by a large circle of friends.” Sorin, 10 years younger than Bulla, lived another seven years after Bulla’s death.

On an unseasonably crisp but sunny spring morning in May, I sat and watched scores of undergrads rush past Flanner Hall, notebooks and North Dining Hall donuts in hand, as they frantically made their way to a final exam in Stepan Center. These young students flipped through their notes for last-second reassurance, with existential questions about the issues of the day and graduation and what comes next necessarily tucked away for the moment. On this very spot, 10 years before Sorin arrived at Sainte-Marie-des-Lacs, the intrepid young Thomas Bulla built his hewn log home, founded his own school and began the precarious work of eking out a life on the frontier.

It is not hard to imagine the fellow frontiersmen — Bulla and Sorin, both strong-willed and driven by faith — discussing the moral, religious and legal challenges posed by slavery, sanctuary and the question of “Who is my neighbor?” Much evidence points to Bulla’s answer.

Sean O’Brien is assistant director of Notre Dame’s Center for Civil and Human Rights and a concurrent assistant professor of law.