Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans

His subjects were Marilyn Monroe, Marlon Brando, Jacqueline Kennedy — and the Brillo Pad box. But Andy Warhol’s greatest impact might have been with his portraits of Campbell’s soup cans. A former advertising illustrator, Warhol’s genius was in taking an instantly recognizable consumer product and, through a coarsening process, transforming it into art. Many of his greatest works look like badly printed newspaper pictures, on purpose. He took commercial non-art imagery and used it to make a comment on our consumer culture. “It is art in the age of the Mad Men,” says George T.M. Shackelford, senior deputy director of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. “There is a kind of willful ordinariness to Warhol’s work, but it is anything but ordinary.” Instead these works, the soup cans chief among them, are infused with irony.

John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence

This painting, which hangs in the rotunda of the Capitol, is perhaps as important for the million copies that it has spawned or the high-school drama presentations it has inspired as for the value it has as a work of art. This is public art of a special kind, passed by hundreds of Americans each day as they visit the home of the government’s legislative branch. The people in the scene Trumbull set before these tourists and lawmakers are real, but Declaration is a manipulated portrait, a high-patriotism painting that is an American political version of formal art lineups, much like European portraits of the apostles. But above all, this is the classic American history painting, portraying a trademark American moment and in turn becoming a trademark American image.

Jackson Pollock, Mural

This 1943 painting, hanging at the University of Iowa but recently a big audience pleaser at the J. Paul Getty Museum, remains a radical American image even though it is almost three-quarters of a century old. Pollock himself described this painting as “a stampede . . . [of] every animal in the American West, cows and horses and antelopes and buffaloes,” adding, “Everything is charging across that goddamn surface.” That goddamn surface has been considered everything from an act of genius to something your grandchild could have done. It was donated to the university by Peggy Guggenheim, a prominent New York art dealer committed to abstract art who commissioned the piece for her home. The amount of opprobrium directed toward this painting, considered one of the most important of the last century, is a tribute to its provocative power.

Mary Cassatt, The Boating Party

This masterpiece, which hangs at the National Gallery, was likely inspired by Edouard Manet’s 1874 Boating, which now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. One part Pittsburgh, one part Paris, Cassatt was at once an international figure and America’s leading impressionist, respected by Edgar Degas and invited into the impressionists’ circle. This painting, made in 1893 and 1894, has a Japanese air to it, especially in the cropping of the boat, the oar and the sail — Cassatt had been actively imitating Japanese prints — and can be regarded as a bridge to post-impressionism. Indeed the entire canvas can be considered a metaphor: The artist, the painting and the figures portrayed are in a boat on the way to post-impressionism.

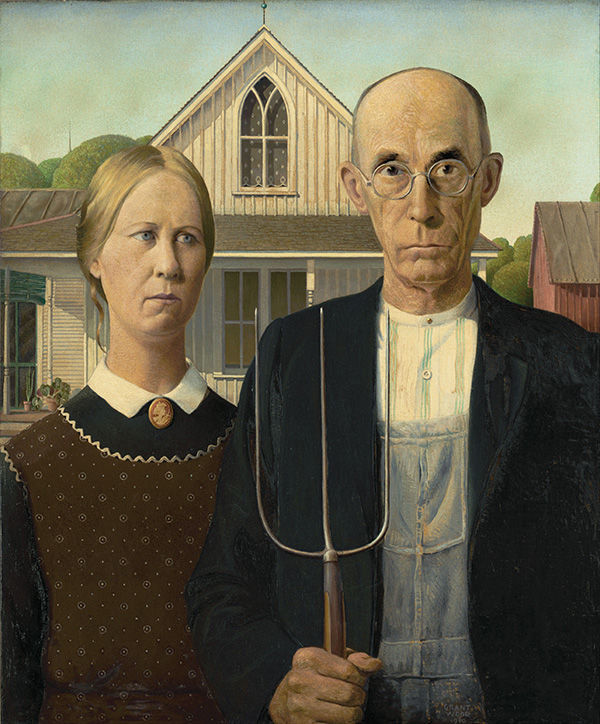

Grant Wood, American Gothic

No painting has inspired more couples’ Halloween costumes, nor more writers’ reveries, than this painting. Nor is any portrait of a U.S. dentist (for that is who the “farmer” really was) more resonant of the American spirit. As famous in America as the Mona Lisa, Wood’s 1930 work expresses the essence of Americanism: plain-spoken, simple, homespun. And yet the painting is a sophisticated work, reminiscent of portraits created by 15th century Flemish artists. Carefully and finely detailed, American Gothic seems naïve, and yet there is nothing naïve about it. In some ways it is a jab at who we think we are — at a time when America, between the wars, was coming into its own as an economic power.

Norman Rockwell, The Problem We All Live With

Many curators and scholars have contempt for Rockwell, seeing him as an illustrator rather than a great painter, or consigning him to a lower rank as a mere practitioner of narrative painting. But many artists, including Winslow Homer, began as illustrators, and Rockwell’s reputation suffers from his very familiarity; we are accustomed to looking at his work on magazine covers or on posters. But this 1964 painting deals with a critical American issue at a critical time in America, and there is nothing saccharine or over-sentimental about it. The tomato splat in the background is not only ugly in terms of what it represents, for it also represents blood, but it is, moreover, a kind of a joke on Pollock and the other artists who employed a drip-and-splatter technique.

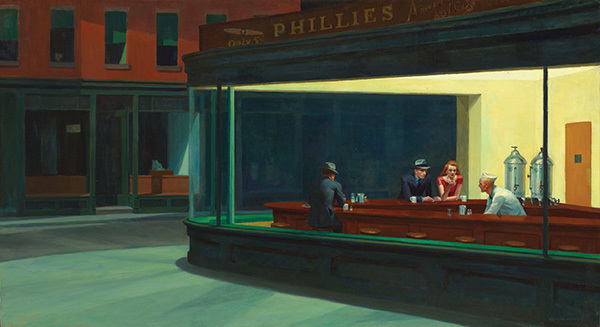

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks

Full of the atmosphere we see in film noir classics and speaking of urban alienation, modern anonymity and the social breakdown of city life, this is one of the most evocative paintings in American history. The brightly lit interior surrounded by darkness can be read as a poetic evocation of modern American lives in 1930, when the work was painted, as well as now. Hanging in the Art Institute of Chicago, this is a painting that makes us desperate to interpret it, and yet everything about it — especially our distance from the scene — thwarts interpretation. And the title Nighthawks has a menacing feeling to it, a visual representation of the world of Raymond Chandler. In his desire to make images like this one memorable, Hopper, like Rockwell, focused on common moments that might be seen anywhere in the American continent.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Cross with Stars and Blue

This painting, resting in a private collection, reflects the crosses O’Keeffe saw in the Taos backyard of Mabel Dodge Luhan’s house. “I saw the crosses so often, and often in unexpected places, like a thin dark veil of the Catholic Church spread over the New Mexico landscape,” said O’Keeffe, whose greatness was in painting the cultural as well as the physical landscape. In this work, which speaks to America’s Native American, natural and Christian heritage, O’Keeffe reclaims and preserves a landscape that by the end of the 1920s was disappearing even as it was being taken over by tourism.

Thomas Moran, Mountain of the Holy Cross

With its visual allusions to change through erosion, deposition and uplift, this painting reflects the country’s view of its manifest destiny to drive across the plains and to command the western part of the continent. The cross reflects the “divinity” implicit in this notion. “In a way this painting is propaganda, marking and confirming this idea of Manifest Destiny,” says Emily Ballew Neff, director of the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art at the University of Oklahoma and president of the Association of Art Museum Curators. “It shows how the West enters the vacuum of attention after the Civil War ends. It shows there was a spirituality and meaning — and a sense of redemption — to the Westering process.”

John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere

This is not the greatest American painting, nor even the best Copley painting, but it is surely the most iconic Copley work. Painted in 1768, before Paul Revere’s celebrated ride, it is freighted with symbolism, not least because it is a portrait of an artisan, not a member of the Massachusetts Bay merchant or political elite, as so many of Copley’s paintings were. This portrait of craftsman-in-shirtsleeves stands as a symbol not so much of the emergence of Revere but of the emergence of a democratic ideal in the 18th century. Revere himself is holding a teapot — plenty of symbolism there in the home of colonial rebellion — and the engraving tools on the counter of a painting created just after the Stamp Act make us wonder what he and his countrymen are going to engrave on this beautiful and polished vessel.

— David Shribman