George Rugg can tell you practically anything you want to know about Notre Dame’s Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, and its growth since he arrived in 1994 to curate the incomparable Joyce Sports Research Collection.

It’s all going up. The number of classes he and his colleagues teach; the research consultations with faculty, students and outside patrons; the sheer number of emailed queries and publishing requests they field from all over the planet; the endowments and budget allocations for new acquisitions, especially unique, unpublished texts and collections of personal papers. The pace in this bibliophile’s heaven is quickening as digitization makes the department’s holdings — more than 175,000 bound volumes, along with 8,000 linear feet of pamphlets, posters, newspapers, letters, private papers, coins, stamps, you name it — ever more accessible.

One statistic eludes him. “I can’t tell you how many students come in here and say, ‘I’m a senior and I’ve never been in here, but it’s really neat and I wish I had.’ We hear that all the time,” he says.

Unfortunately, many more students somehow pass four years at Notre Dame without getting even that far. So, in case you missed it and you’re not sure where Rare Books is, imagine a curling, yellowed map of campus — not unlike the beauties you can find in the Butler and McGrath collections of maps and sea charts of Ireland, or the Scanlan maps of the Great Lakes. Picture galleons plying Saint Mary’s Lake and “Here be dragons” scrawled where Douglas Road used to be. The black ‘X’ would mark the southwestern corner of the Hesburgh Library’s main floor.

This is where the treasures are kept. Every book in the library published before 1830 lives here, but so do important literary first editions, books once owned by historical figures and volumes that come in through purchases or donations of valuable private collections. The Dante collection is well known, and it may surprise few that theology is a strength and includes a one-of-a-kind assemblage of primary source materials on the Second Vatican Council. But Irish music? Colonial currency? Records of the Inquisition? These are strengths, too. All this and more. Seek, and ye shall find even Spanish gold ingots from the 17th century.

- Related articles

- At 50, a makeover behind the mural

During Rugg’s tenure the full-time staff has grown from four to nine, their labors rounded out by subject librarians who primarily work upstairs on the general collections. The work is interactive and collaborative. Staff members create exhibits for the lobby just off the library concourse and online finding aids for the inquisitive scholar who may be connecting from Kiev — or Keenan Hall. They teach classes as guest lecturers, host local seniors and schoolkids, and, depending on their expertise, offer courses in paleography — the study of historical manuscripts. They work with faculty and graduate students to tailor new acquisitions to their needs. Always, they keep an eye on what’s available from dealers and prospective donors, performing a kind of Antiques Roadshow with judiciously exercised purchasing power on behalf of the life of the mind.

David Dressing, the library’s Latin American and Iberian Studies specialist, came two years ago from Tulane and likes to browse the special collections in his field during lunch. “It takes a while to get to know a collection,” he says, and the pastime helps him help the academic departments he serves.

The most important task is helping researchers find what they need. It’s easier than people realize. Want to spend an hour with an incunable (a pre-1501 printed book; Latin cuna = cradle, for the “cradle of printing”)? Maybe some Civil War letters? “You don’t have to come here with 10 different letters of recommendation,” notes curator David Gura, the interim department head who even tweets his “Find of the Day” to those curious about the world of letters before 1600. You just need to talk to a curator or librarian, learn how to handle the materials, and you’re off.

Which brings us back to those astonished seniors and their last-minute discovery of this intellectual treasure trove. Says Gura, “What is the point of having this stuff if no one ever gets to see it?”

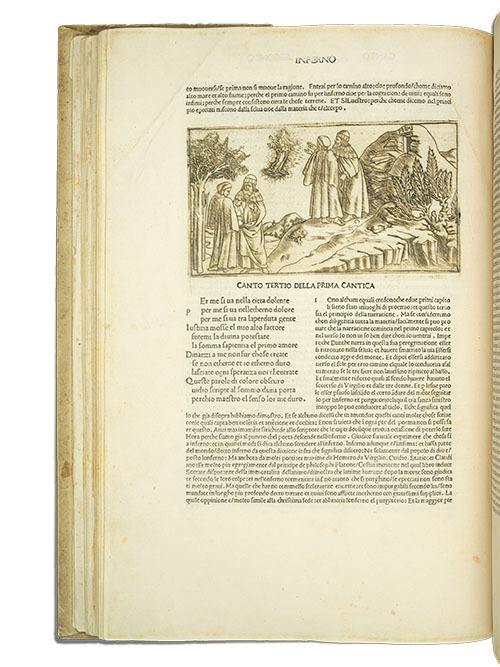

“Commentary of Cristophoro Landino, Florentine, on the Commedia of Dante Alighieri, Florentine poet,” 1481. Weighing in at 11½ pounds, this extra-large edition of Dante’s epic of the afterlife was intended to make a statement. Scholars under the patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici conspired to produce a critical volume superior to those already published in other Italian cities as a way to reclaim their hometown hero, but the product reveals the roughness of the shift from manuscripts to the printing press. The poem’s text and the commentary don’t correspond, and the scheme of paste-in illustrations conceived by the Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli was botched by the engraver and, in most copies, left incomplete. Father John Zahm, CSC, bought the book and others from the Italian bibliophile Guido Acquaticci in 1902 as the basis of a collection that would make Notre Dame a top-tier destination for Dante scholars.

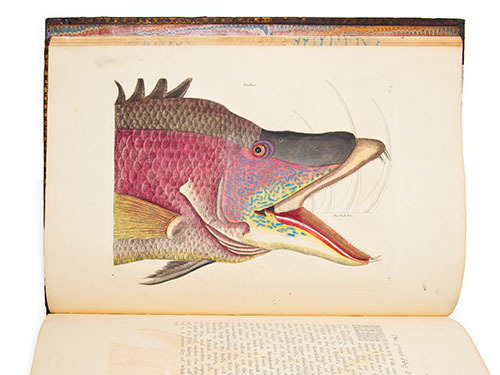

The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, 2nd edition, 1754. One hundred years before Audubon, there was Mark Catesby. An English artist and naturalist, Catesby traveled the southeastern colonies of North America collecting specimens. Over 17 years, he published in London hand-colored copies of his own copperplate engravings of the region’s flora and fauna for his subscribers, mostly wealthy science enthusiasts. Among its virtues is its record of once-plentiful species such as the Carolina parakeet and the passenger pigeon that are now extinct. Notre Dame’s copy, in excellent condition, is a favorite with the public.

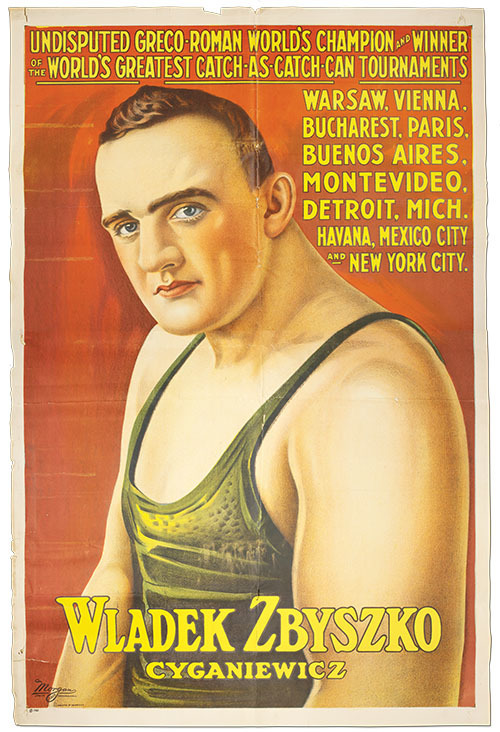

Lithograph poster of Wladek Zbysko, 1921, from the Jack Pfefer Wrestling Collection. Professional wrestling has no credibility anymore, but in the 1920s it was one of America’s most popular pastimes. Promoter Jack Pfefer was a force in wrestling’s rise as theater — and its fall as a sport. Pfefer’s collection of business records, correspondence, press clippings, photographs and promotional materials spans his 45-year career and is but one facet of Notre Dame’s eminence as a repository for sports research. The cache includes 40 posters like this one. “People write about all sorts of American popular culture,” says special collections curator George Rugg. “People do write serious books on professional wrestling. And if you’re going to do it, you have to come here, because there’s nothing like this.”

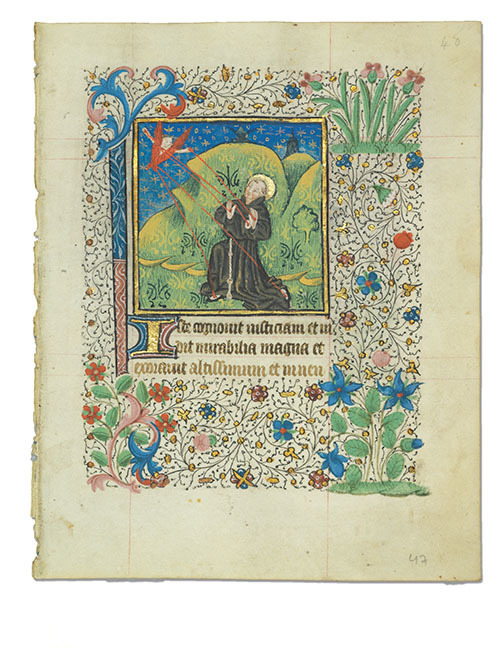

Breton Book of Hours, c. 1450. Part of an important collection of medieval manuscripts until its gentleman-scholar owner died in 2010, this illuminated prayer book, handcrafted for a well-to-do 15th century woman in northwestern France, was sold to an anonymous buyer at a Sotheby’s auction. The book was then cut apart so its pages could be sold to amateur collectors seeking pieces of “medieval art.” This is called book-breaking, a lucrative practice deemed unethical by librarians that is further enabled by the heightened anonymity and limitless market reach of legitimate Internet auction sites like eBay. David Gura, the curator of medieval and European manuscripts, is working to retrieve the scattered leaves and reassemble this rare example of devotional practice from Brittany. The saints referenced in the litanies and liturgical calendars are potent teaching tools for budding medievalists learning how to date and place such books.

Liber Chronicarum, 1493. Better known as the Nuremberg Chronicle, this account of world history from creation to the printing press features hundreds of illustrations — often one woodcut would represent more than one person or city, says Western European history librarian Julie Tanaka — making it the most illustrated of early printed books. Notre Dame has two copies, a first edition in Latin and a “pirated” German edition published in Augsburg, Germany. The image of the mythical Pope Joan, who at the time was believed to have existed during the Middle Ages, was excised or defaced in many copies, but Notre Dame also possesses this leaf from another copy showing her likeness intact.

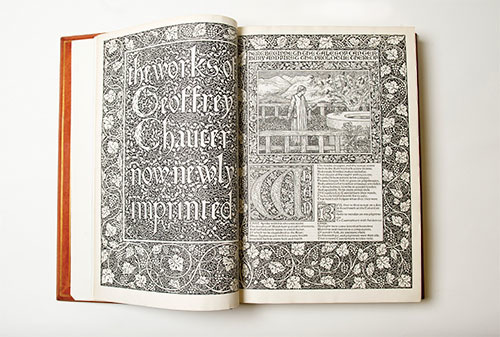

The Kelmscott Chaucer, 1896. By the Victorian era, books had gone the way of all man-made goods — cheap and machine-produced with little regard for quality. Late in his career as the father of the Arts and Crafts Movement, and horrified by the popular editions of his own writings, the English artist and social critic William Morris studied medieval bookmaking and founded the Kelmscott Press. Its edition of The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, handcrafted in every detail from paper and binding to the rich illuminations and Morris’ typeface design, is “one of the undisputed treasures in the history of printing,” according to English and French literatures librarian Laura Fuderer. Morris died soon after its production; his influence publishing endures.

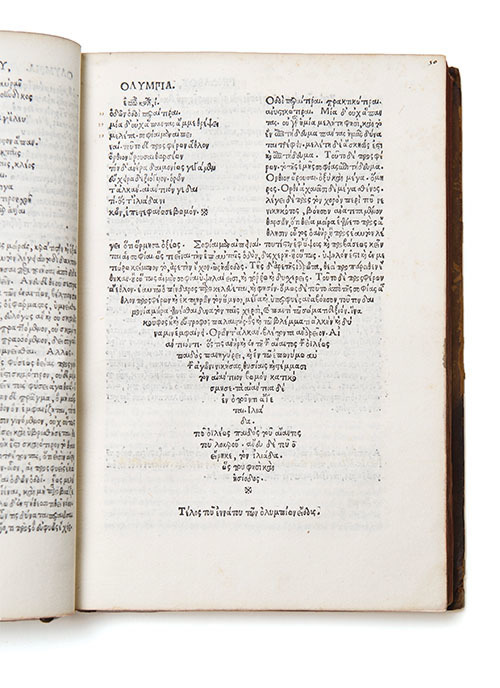

Pindar’s Odes, 1515. Renaissance Rome was a center of Greek scholarship and a magnet for talented teachers and calligraphers. Zacharias Kallierges worked for Pope Leo X and produced the first book printed in Rome entirely in Greek characters, this volume of Pindar’s victory odes with commentaries. Kallierges designed the type himself — an exacting task because of Greek’s numerous diacritical marks, which were tiny and cut separately from the letters and likely hooked onto them when setting a page. Classics and Byzantine Studies librarian David Sullivan acquired the book recently as part of his work to build Notre Dame’s collection of early modern print editions of the classics in Greek.

Introduction to the Devout Life, 1641. Saint Francis de Sales first published this classic in 1609 as the fruit of his years as a spiritual director. Addressed to the human soul, it was soon translated into every major European language and read by Catholics and Protestants alike en route to becoming a best-seller of the 17th century and of Catholic literature ever after. This edition, printed in Paris, is one of myriad editions in Notre Dame’s possession, a collection that allows scholars to study the work’s reception and use over time, and its place in Catholic thought. Generous endowments have enabled similarly comprehensive collection strategies for many Catholic titles and authors — one reason, says theology librarian Alan Krieger, that Notre Dame is the leader in Roman Catholic theology holdings in the United States.

Mystical Images of War, 1914. At 33, Natalia Goncharova was an established painter and leader of the Russian avant-garde when the First World War began. She soon produced this cycle of lithographs, a neo-Primitivist meditation on religion, mythology and destruction that stands prominently among the first artistic responses to a war that would leave 37 million people dead or wounded. Fewer than 200 books were printed. Russian Studies librarian Natasha Lyandres says Notre Dame’s copy enhances a growing accumulation of resources documenting 20th century Russia, especially the rise and fall of the Soviet Union.

Pine tree shillings, c. 1652; New York note, 1709; Massachusetts “soldier note,” 1775. When the Smithsonian and other museums prepare exhibits on money in colonial America, they come to Notre Dame. Paper money and coins are useful to the study of economic and political history, says associate University librarian Louis Jordan, the former head of Rare Books and Special Collections. Notre Dame’s collection was greatly enhanced when Robert Gore ’31 donated his personal collection and funding to keep building it. Along with the Joyce Sports Collection, the coins attract by far the most requests for image publication rights. The shillings were among the first British coins minted in the New World. The New York note is the first paper currency printed in the future global financial capital. And the Massachusetts? Jordan says it was printed by Paul Revere and was probably in a soldier’s pocket at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

The Holy Bible, 1805. Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton’s personal Bible is a piece of Catholic Americana — her underlining and notations affirm what rare book librarians call its associative value and make it a relic, too. The book itself is important. Printed by Irish émigré Mathew Carey, it’s a copy of only the second edition of the Douay-Rheims translation of the Latin Bible into English published in the United States. Catholic Studies librarian Jean McManus says Carey worked for Benjamin Franklin in Paris and set up his Philadelphia shop with a gift from the Marquis de Lafayette, producing this Bible when there were still few Catholics in the new nation.

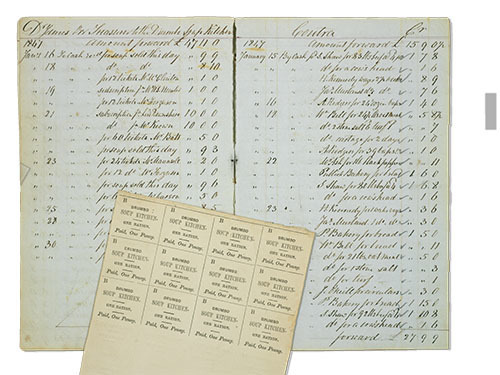

Drumbo soup kitchen account book and penny ration tickets, 1846-7. Some treasures await full discovery, like this window into microeconomics and nutrition during the Irish potato famine. Irish Studies librarian Aedin Clements says nothing is known about the Dr. James Orr who kept the accounts, and even the town is in question — is it the Drumbo in Donegal or the one near Belfast? Subscriptions to support the kitchen cost one pound, and the inventory included barley, pepper, salt, bread and, once, even a cow’s head for the low price of one shilling and sixpence. “All fair game for a student willing to do a serious bit of work on it,” Clements says.

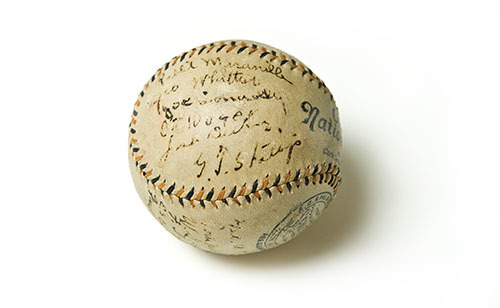

Boston Braves team-signed baseball, 1914. The Joyce Sports Research Collection includes 64 autographed baseballs, which have little value for scholarship per se but feature the signatures of scores of 20th century ballplayers from Hank Aaron to Cy Young. This 1914 Braves ball is one of the earliest examples of the team-signed ball, presented to Hall of Fame second baseman Johnny Evers near the end of the “miracle” season in which the franchise emerged from last place in July to win the World Series. The signatures on this panel include Evers’ fellow Hall of Famer Rabbit Maranville and the manager, George Stallings. The ball was donated to Notre Dame in 1977 by John J. Evers Jr.

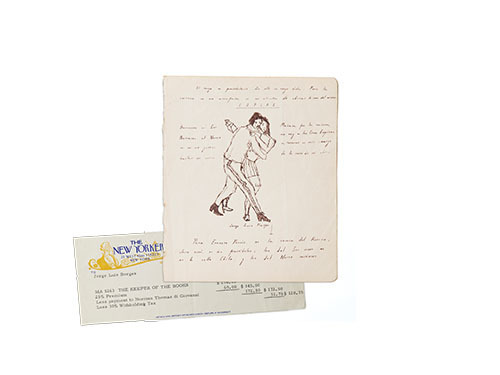

Receipt c. 1969 and undated poems and sketch by Jorge Luis Borges. Thanks largely to the patronage of Argentina-born Robert E. O’Grady ’63, who died this year, the library now has one of the most important collections from South America’s southern cone in the United States. One gem is this undated manuscript page, a pair of short poems and sketch of a couple dancing the tango by Jorge Luis Borges, among the most influential writers of the 20th century. Borges loved the tango: the dance; its music and poetry; the story behind it. Notre Dame’s Professor María Rosa Olivera-Williams used the unique image in recent lectures about the tango.