I’ve had 50 years to think about Mike Trombley.

William D. Moss/Wikimedia Commons

William D. Moss/Wikimedia Commons

To recall the hours we shared.

To speculate on what he would have become.

To contemplate, with ineffable sadness, what his final moments were like, thousands of miles from home, in Vietnam.

When I think of him, the first image that comes is the way he came down from the tall, tar-shingled old house at the top of the hill. Waiting at the traffic light where we began our hitchhiking effort to get to school, I would see him cross the four-lane road that separated us, then amble the last block to where I stood. Like Satchel Paige, who believed in training by rising gently up and down from the bench, Troms, which is what his friends called him, seemed never to hurry. Even on the coldest Michigan winter days, he refused to button the top button of his St. Cecilia High School letter jacket. Never wore gloves. A hat was unconceivable. It was as though he stayed warm by simply refusing to accept the environmental evidence around him. Or maybe he grasped early on that seeking comfort in life was eventually a fool’s errand.

If I could have picked an older brother, I would have selected Troms, my senior by a year. We played on baseball and football teams together, but the best of times were the shared conversations — the bull sessions. For Troms, B.S. was an art form to be honored. And practiced frequently.

Sometimes on sweltering summer days we hung out in the small, congested basement of his family’s house. There was room enough for weights and a bench press table, along with a dart board, the kind you find in a pub. Troms would have made a great pub owner.

There was also a phonograph. The jazz pianist Ramsey Lewis was his favorite. And Troms had scored a few Redd Foxx albums — this was several years before Sanford and Son made Foxx quasi-respectable. At the time, Foxx was regarded as a highly risqué stand-up comic, his records filled with sexual double-entendres. As adolescent males, we laughed boisterously, even at the parts we didn’t yet fully understand.

I recall what else he liked: Jonathan Winters. The comic strip B.C. Roger Miller. The wrestler Dick the Bruiser, whose gruff speech he could imitate with the best. Rocky and Bullwinkle. And Motown: No British Invasion for Troms. The radio was tuned to WCHB, the Detroit soul station, all the time.

I had my first beer with Troms, and a couple of his other classmates. Not just my first, but my first two or three dozen Carling Black Label lagers. Testing boundaries was another way of bonding.

He was an average student like many teenage guys, setting a low priority on classwork and homework. I suppose that is why Coach Insell appeared shocked when teammates elected him captain of the baseball team his senior season. Troms had never campaigned for anything in his life. What the guys knew was that he had the dependability of someone who lacked pretension. And in fact, his ability to satirize pretension was one of his most engaging traits.

He covered center field like a linebacker, the position he played in football — he got it done more by determination than grace. In one season’s final game, we needed to beat St. Andrew to tie them for the league championship. They had a tall, left-handed pitcher who hadn’t lost in four seasons, big-league scouts checking out his every performance. The season came down to the final inning, two outs, Troms up. He banged a solid hit up the middle to tie the game, and we ended up winning.

After the game, in the bus taking us back to our school grounds, I saw him smile.

When he graduated from high school in 1965, Vietnam was just becoming part of every evening newscast. LBJ was pouring in more U.S. troops to sustain the faltering regime in the south. Casualties were starting to rise, but the word “quagmire” was not yet in common use.

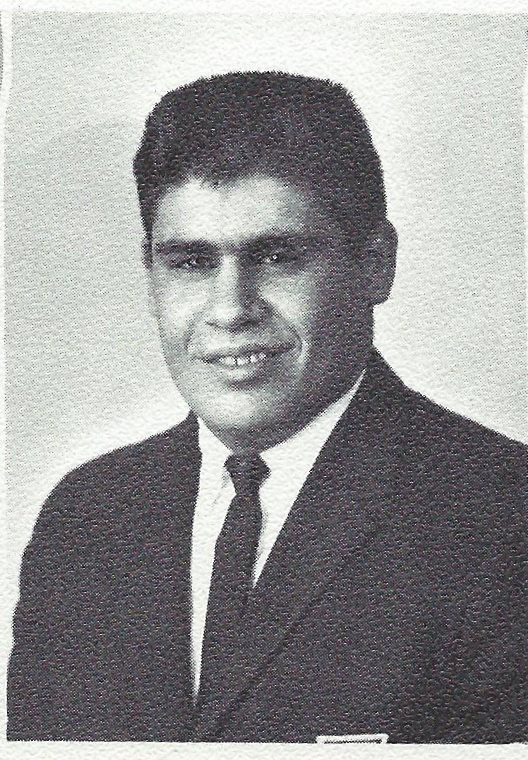

Mike Trombley as a senior in high school, 1966. Photo courtesy of the author.

Mike Trombley as a senior in high school, 1966. Photo courtesy of the author.

Uncle Sam sent greetings in early 1966. Troms figured if he was going to be drafted, he would join the Marines, like two of his older brothers. The oldest, Duane, had died during World War II on Iwo Jima, a few years before Troms was born. I tried to imagine how that might have affected family dynamics as he grew up.

The night before he was to report for induction, we talked at length in his basement. He joked about spending the next Christmas in exotic Southeast Asia.

As I prepared to begin my freshman year at Notre Dame, his first letter arrived from Camp Pendleton. The Marine experience had put a fine edge on his deadpan humor. He relayed how he and his fellow recruits were cut off from the outside world. “Now I know why they closed up Alcatraz, they don’t need it. We don’t even listen to the radio.”

A few weeks later, he related: “We were taught how to rip out a guy’s throat, break his nose and then drive it into his brain, rip out his spine, shatter his eardrums, and pop out one eye and then put it in front of his other eye so he can see what we did to him. Next class we’ll learn how to kill somebody.” He further observed, “They teach you to hate Charlie so you won’t have any qualms about killing him.”

He also implored me not to enclose anything extra in my letters. One of our beer-drinking buddies had sent him a picture of Miss April. As a result, the drill instructor required Troms to wear the photo on his chest, walk to the next platoon, perform an exhausting number of calisthenics, and then tear the photo into half-inch pieces. “Whatever you do, don’t send me anything but B.S.,” he wrote.

He came home from Camp Pendleton in the summer of 1966. More troops were on their way to Vietnam, and more people were raising questions about the wisdom and morality of the policy. One afternoon, over burgers, I asked Troms if boot camp had included any discussion of the reasons for the war. He replied that there was a presentation on it one afternoon, but most guys were tired from the morning activities and had pretty much tuned it out.

We went to a Tigers ball game, and pitcher Earl Wilson came in as a pinch-hitter in extra innings and beat the first-place Orioles with a home run, the high fly ball nestling just over the 340-foot mark on the left field line. The moment of elation gave us a reprieve from the reality that Troms would soon be heading overseas.

He shipped out in October, destination Da Nang. News reports indicated the war was getting more intense. Soon word came back to the States that Lenny Morgan had died in Vietnam. A few months later, it was Dan O’Donnell who was killed. Both had graduated from St. Cecilia with Troms, a class with only 42 males.

The letters from Troms came less frequently now, and the notes that arrived were worrisome:

“We used to run into big V.C. units about 2 times a month. Now it’s every day . . . I’m in the 2nd platoon now; the reason for that is that they had 22 casualties when an amtrack hit a mine. The amtrack was carrying napalm . . . Would you believe that I’m one of the few guys in my platoon that ain’t got a ‘purple heart’ yet? Man, that’s one thing I don’t plan on getting.”

On a late summer day I took the dreaded phone call from his brother, Don. I hung up the phone and told my Dad, a World War II vet. I saw him shake. “That damn war,” is all he said. No three words were ever more true.

I sat alone in the back yard, with chaotic thoughts about what had been, what would never be, and what could explain the carnage. Was it maliciousness? Greed? Miscalculation? Hubris? Madness?

The sound of the wind, the sight of a few white clouds against a blue sky, the texture of the grass — each appeared more vivid to me than ever before. They were all reminders that the world would keep on turning without any of us.

The solitary thing that was clear was that I would never be the same.

The Detroit News reported the next day that Lance Corporal Michael Trombley, 20, had died near Quang Nam as the result of “fragmentation wounds from a Viet Cong boobytrap.”

The story continued: “We could accept Duane’s death in World War II,” Mrs. Trombley said, “because we felt he died fighting for America.

“But we’re pretty bitter about what happened to Mike. Vietnam is a useless, senseless war.”

A half-century later, our troops are long gone from Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh won. Coca-Cola bottles and distributes in the country. Vietnamese contractors make Nike shoes. It is reported that American tourists are warmly welcomed in the country.

In the U.S., documentary filmmaker Ken Burns’ latest work for PBS debuts. It focuses on Vietnam and is based on interviews with the people who were there during the war.

In Washington, there is a polished, black granite wall. It carries the names of 58,318 men and women who did not live to give their accounts. Yet each person remembered there left behind family and friends who could, beyond the tears, relate their own stories.

This one is mine.

Ray Serafin is a freelance speechwriter in the Detroit area and co-author, with Frank Pomarico ’74, of Ara’s Knights: Ara Parseghian and the Golden Era of Notre Dame Football.