In the summer of 1989, 29-year-old Norma Kreilein finished her pediatrics residency at Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center, packed up her house in Altadena and drove east with her husband, Mike, to Indiana. Norma was a country girl returning to her roots. She grew up on a family farm in a rural hamlet known as Duckville, a few miles outside of Ferdinand, a town of about 1,500 people in Dubois County, in southwestern Indiana. Her parents were third-generation German Catholic immigrants farming the same 200 acres their grandparents settled on back in the 1850s. They raised cattle and grew corn and soybeans, but the economics of the farm business were brutal, and the family of 10 struggled to make ends meet.

In her teens, Kreilein worked as one of her high school’s janitors, scrubbing toilets and sweeping floors after class, and babysat on the weekends. She dreamed of becoming a doctor, studied hard and, in her senior year, was accepted to Notre Dame. That summer she saved money for college by working at a local factory, cleaning engine rods. In the evenings, after her factory shift, she waited tables at a pizza parlor. When she headed off to South Bend in 1978, she was the first person in her family to attend college.

Kreilein graduated from Notre Dame in 1982 with a pre-med degree, and from the Indiana University School of Medicine in 1986. After moving back from L.A., she took over a family medicine office in Jasper, a city of about 15,000 people a few miles north of Ferdinand, and turned it into a dedicated pediatrics practice. Straight off, she noticed a few peculiarities. For one, the family practitioner whose patients she assumed had a surprisingly relaxed approach toward treating children. Mothers often simply called the office, asked a nurse for antibiotics or decongestants, and received prescriptions over the phone. Some sick kids were medicated five or even 10 times before ever seeing a physician. Kreilein ended this arrangement.

She also assumed care for dozens of children on allergy shots, which seemed an abnormally high number for the area’s small population. It was a puzzling phenomenon. She noticed that kids under her care who left the area on vacation often saw their allergy symptoms decline substantially while they were away. Then there were the stories of people who moved to the area and saw allergies dramatically worsen, or who developed sinus problems, or worse. Working 50- and 60-hour weeks and raising two kids, she never found the time to investigate further. “Doctors discussed it frequently,” Kreilein says. “It was just a commonly known fact that we were an allergy belt.”

Kreilein tells me about her background as we sit in an unused examination room she’s repurposed as an office in the pediatrics unit at Daviess Community Hospital, in Washington, Indiana, a small city about 40 minutes northwest of Jasper. I’ve come to interview her because not long after her 50th birthday, after more than two decades as a successful small-town physician, Kreilein took on a new and controversial role as an outspoken opponent of a major industrial project proposed for Jasper. It was a sea change in her life that surprised even her. Just a few years later, she is seen as an environmental hero by some Jasper locals and a hysterical Chicken Little by others. “I never in my life believed that I would get sucked into something like this,” she says.

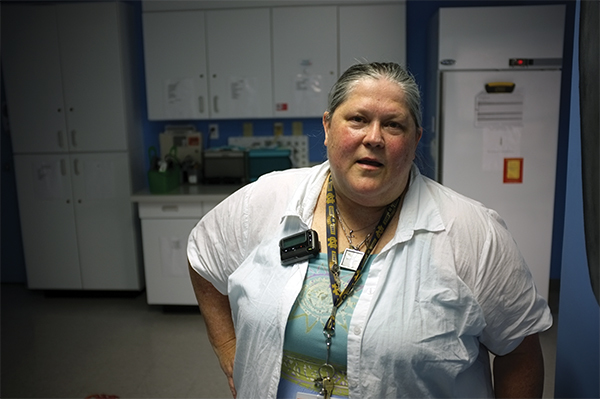

It’s a Sunday afternoon, and the pediatrics clinic is quiet and dark, but Kreilein is on call and cannot stray more than 15 minutes or so from the hospital. She wears a long, white dress shirt, like a doctor’s coat, over a simple blue and turquoise patterned dress, with a pager clipped to her lapel. Around her neck hangs a lanyard that holds her hospital ID card and a set of keys, the strap featuring the familiar blue and gold Notre Dame insignia. It’s one of many signs of alumni pride I notice throughout the day, like the Fighting Irish placard on her otherwise undecorated office wall and the “We Are ND” license plate holder on her Chevy Suburban.

Kreilein is 54 years old, with a broad face and ruddy complexion, her iron-gray hair pulled back in an all-business ponytail. She looks tired; as she describes the past few years, I get the sense that she is weary in a deep-down, profound sort of way. Yet once she gets talking her apparent fatigue melts away, to the point that at times I can barely get a word in edgewise, fighting upstream against a torrent of facts and figures, anecdotes, rants and digressions.

In great detail she describes the consequences of her activism, which upended her life, destroyed longstanding professional relationships, and exacted a heavy financial and emotional toll. Most seriously, Kreilein quarreled so frequently with the partners in her Jasper pediatrics practice that she eventually sold her share of the business and took a new job working for the hospital in Washington. She rented a small house in town and returns to Jasper, where her husband and teenage son still live, on the weekends.

The situation that changed everything for her started in 2007 when officials in Jasper faced a dilemma over the future of the city’s coal-fired power plant. The 14.5-megawatt facility, built in 1968, is pygmy-sized compared to the privately owned behemoths in the region, and recent shifts in the Indiana electricity market, including a price spike for the special type of coal the plant used, had left it increasingly uneconomical to run.

So in 2010, Jasper’s Utility Service Board, which manages the city’s water, power and sewage, announced it was seeking proposals from the private sector to burn something other than coal in the plant. One businessman pitched them on burning “turkey litter,” a polite euphemism for excrement; Dubois County is the turkey capital of Indiana, with millions of birds raised and killed within its borders each year. Others suggested burning “municipal solid waste,” also known as garbage, or even shredded tires. These were rejected.

Then in December 2010, the utilities board heard from a Georgia company, Twisted Oak Corporation, with a proposal to burn “biomass” in the form of miscanthus, a dense Asian and African grass that can reach 12 feet in height. Miscanthus has been used in Europe as a feed stock for power plants for several decades but had yet to be used commercially anywhere in the United States.

The Twisted Oak plan also called for the construction of a natural gas turbine alongside the old plant. All told, the project would result in a private investment in the neighborhood of $100 million. City leaders believed Twisted Oak’s pitch that the shift to biomass and the addition of the gas turbine would make the power plant profitable again, and they put the project on the fast track to approval. The plant was to be renamed the Jasper Clean Energy Center.

Local opposition to the biomass project was led at first by a local minister, Chris Breedlove, whose daughter suffered from asthma. Breedlove and others argued that the air in Jasper was already polluted by heavy industry and the emissions from the biomass plant would further threaten people’s health. City leaders vehemently disagreed, contending that the anticipated emissions levels from the plant were too low to pose any major risk and that the economic benefits to the city outweighed any potential harm. The Twisted Oak Corporation, the Georgia developer behind the proposal, launched a website declaring that the project would create 200 local jobs and generate $200 million in “community impact.”

The debate over the biomass project was already well underway when Kreilein got involved. She read up on air pollution and its impact on human health, and concluded that the anticipated emissions from biomass plant did pose a risk to human health. Then she started speaking out, loudly and frequently, in a variety of forums, ultimately becoming president of Healthy Dubois County, an advocacy group that formed in opposition to the biomass plant. When the Jasper City Council voted in the summer of 2011 to enter a lease agreement with Twisted Oak for the biomass plant, Healthy Dubois County sued them in state court. The suit ultimately hinged on whether city officials violated Indiana’s open door law by negotiating with Twisted Oak in off-the-record meetings. Kreilein poured thousands of dollars of her own money on the advocacy group’s legal fees in what turned into a bitter, messy and protracted legal fight.

As the fight dragged on, Kreilein found herself questioning much more than just the biomass project. She eventually came to believe that the air in southwest Indiana — home to some of the country’s largest coal-fired power plants — was dangerously polluted by a largely invisible stew of airborne industrial particles. Her proclamations on the state of the region’s air now range between the dire and the apocalyptic. “People need to know this is a crisis,” she says. “The true amount of suffering is astronomical.”

To Kreilein, air pollution is the most likely culprit behind what she considers a high prevalence of allergies and other respiratory problems in the area. This is essentially a doctor’s educated guess: No one has studied the area or the issue in enough depth to know one way or another. But that lack of studies — and what she sees as a lack of interest by state regulators in aggressively collecting reliable air quality data — is itself a big part of the problem, she says. Of special concern to her is Indiana’s infant mortality rate, which in 2013 was 7.7 deaths per 1,000 births — the sixth worst in the country.

Indiana’s health commissioner has decried the infant mortality rate as “horrible” but pointed at causes such as obesity and smoking. Kreilein, however, sees a link to pollution from coal-fired power plants, which generate 84 percent of Indiana’s electricity and release millions of pounds of toxic pollution into the air every year. Indiana’s reliance on coal is the fourth-highest in the country, after Kentucky, West Virginia and Wyoming.

Kreilein understands that for some people in Jasper, a deep-red town in a conservative-leaning state, environmentalism is for hippie leftists. But it’s not a love of nature that motivates her. “I’m not a tree-hugger. I’m a kid-hugger,” she says. “My problem with pollution is that it pollutes children’s bodies. The problem with mercury is that it ends up in a kid’s brain. And the problem with particulates is that it ends up in a kid’s lungs.”

Kreilein’s concerns about air pollution in Indiana reached a wide audience last year when she appeared in an in-depth investigative report by Bob Segall, a reporter for WTHR-TV Channel 13 news in Indianapolis. The investigation found 85 industrial facilities in the state — including some of Indiana’s largest coal-fired power plants — listed on the EPA’s “high priority violator” list. Inclusion on the list means that EPA data suggests the facility is in violation of the Clean Air Act. Segall also reported that enforcement actions by Indiana regulators against polluters had declined by 60 percent since 2007.

In the newscast, Keith Baugues, assistant commissioner of the Office of Air Quality, Indiana Department of Environmental Management, dismissed any notion that the state had an air quality problem or that its regulators were failing to aggressively pursue polluters. “The air quality is very good in Indiana,” he told Segall.

Baugues also said his agency was “doing a good job” in pursuing emissions violators and the number of enforcement actions had fallen because polluters “are paying attention.”

Environmental advocates quoted in the Channel 13 report scoffed at this premise. "When companies break the air regulations, they really ought to face penalties, but they usually don’t even get a slap on the wrist,” said Richard Van Frank, a retired biochemist and board member of Improving Kids’ Environment, an Indianapolis nonprofit group.

Kreilein has a vocal group of fans grateful for her activism in Jasper. Among them is Rose Hoffman, a mother of six who lived in Jasper with her husband, Dr. John Hoffman, a family physician, for 13 years before moving to Champaign, Illinois, almost two years ago. Several of Hoffman’s children developed health problems while living in Jasper; her youngest daughter had nighttime coughing fits and one of her sons suffered recurring migraines that often kept him home from school. Her husband even needed weekly allergy shots for the first time after moving to town. But most strikingly, after a lifetime of good health, Hoffman suffered a mysterious and near-fatal case of pneumonia in 2005 that left her health permanently damaged. “The left lung is totally nonfunctional,” she tells me. “The pulmonologists don’t understand it at all.”

Hoffman pulled back from the brink, but her health remained poor. Then her husband took a job in Champaign, and the family relocated. Almost immediately after moving, she began a rapid turnaround. “We were absolutely stunned by how quickly I began to improve,” she says. “My day-to-day functioning improved exponentially.”

After the move, her daughter’s coughing fits stopped, her son’s migraines nearly vanished and her husband stopped needing allergy shots. But whenever Hoffman returned to manage the sale of the family’s house in Jasper, she started wheezing again. “The air in Jasper is scary to me,” she says. “It makes it hard for me to breathe and function.”

In an email to me, her husband says, “It is my opinion that the current levels of high particulates helps explain why infants, children and adults have respiratory symptoms in southern Indiana that sometimes they do not face when they are in other parts of the country.”

Hoffman admires Kreilein for taking a stand in Jasper. “I have huge respect for Norma,” she says. “She’s just continued to advocate for the people who didn’t even know they needed advocating for.”

Then there are those who have found themselves in her crosshairs on the biomass issue, a group that includes some fellow Notre Dame alums. They see Kreilein’s advocacy as over the top and crossing the line into fearmongering. And they call her crusading, confrontational style aggravating and infuriating.

Gerald “Bud” Hauersperger, the general manager of Jasper’s municipal utilities, graduated from Notre Dame in 1980 with a degree in electrical engineering. As a member of the Jasper utilities commission that approved the lease on the biomass plant, he has clashed repeatedly with Kreilein in a variety of forums. In his eyes, locals are wearying of her ominous proclamations, expressed at public meetings and in a “constant barrage” of letters to the editor. “I think people are just getting tired of it, and they don’t want to hear it anymore,” he tells me.

Hauersperger is also teed off by what he sees as personal attacks leveled against him and other city officials by members of Healthy County Dubois. Members of the group — including Kreilein — have portrayed him and other officials as “corrupt and evil,” he says.

“If you don’t agree with her, then you are automatically an enemy to her,” Hauersperger says.

I can understand where he’s coming from, because over the course of several long discussions with Kreilein, I’ve heard her paint those she considers to be abetting pollution in extraordinarily harsh terms. More than once she compares Jasper officials to Jerry Sandusky, the former Penn State assistant football coach now serving 30 to 60 years in prison for child rape, and the school officials who covered up his crimes. In another extended analogy, she compares Indiana regulators and political leaders to the Nazi Party, for looking the other way while the coal industry fills the air with deadly emissions.

Both analogies strike me as overblown and highly likely to offend people who might otherwise be sympathetic to her cause. Just to be absolutely clear where she stands, I ask her directly — my notebook in hand — if she honestly believes Jasper’s utility board and Indiana’s environmental regulators have sunk to the same moral plane as Sandusky and the Third Reich. “I personally think that we’ve crossed that line,” she says. “But when you throw those words around it doesn’t make people very happy.”

When I later ask Hauersperger for a response on this, he laughs bitterly. “How do you deal with that kind of comment?” he asks.

There’s a difference between reading statistics about air pollution on a computer screen and seeing (and smelling) it in the real world. So on the day I visit Kreilein in Washington, after talking a while in her office, we take a 20-minute trip to look at the Petersburg Generating Station, a coal-fired power plant. Kreilein has mentioned it a few times, and I’d like to see it with my own eyes.

We climb into her tank-like Suburban and drive through Washington and pull onto the county highway, a meandering road that winds through farmland and up and down rolling green hills. It’s not long before smokestacks appear on the horizon, pumping a billowing plume hundreds of feet into the air. From this distance — maybe five miles — the plume is flat white. The color signifies the harmless byproduct of an old technology: coal is burned to create steam, which spins turbines, generating electricity, and releasing huge clouds of water vapor.

A few minutes later we round a curve and overtake a long freight train lumbering by to our right, its cars heaped high with jet black coal. I start to notice that the white plume of the plant is not so white after all but is tinted yellow-brown. Then the smell hits me through the open window: a charred aroma, sharp and tangy, like a backyard barbecue doused with lighter fluid. A moment later we enter the outskirts of Petersburg, a town of about 2,400 people and the Pike County seat, and my throat suddenly feels raw. The smokestacks loom over down-at-the-heels single-family homes. A couple of kids play soccer in a small front yard.

Kreilein points toward the plume. “You see that brown?” she says. “That’s not water vapor.”

A few days later, I try to find out just what was in the air in Pike County. The Petersburg power plant, it turns out, is one of the largest in the state, with a capacity of 1,870 megawatts, enough to power Rhode Island on a summer day. The EPA website says that in 2013 Pike County had 18 days that were “unhealthy for sensitive groups,” like young children and the elderly, and two days that rated as “unhealthy.” According to the EPA, “unhealthy” means when “everyone may begin to experience some adverse health effects, and members of the sensitive groups may experience more serious effects.”

There is a hitch: The EPA data — which it receives from the Indiana Department of Environmental Management — is incomplete. The Petersburg monitor tracks just one pollutant, sulfur dioxide. There are five other emissions that the EPA considers “criteria” pollutants: ground-level ozone, small particulate matter, carbon monoxide, lead and nitrogen dioxide. Of these, the EPA says, particulates and ozone “pose the greatest threat to human health.”

When I dig further into the data, I notice something peculiar. Among the major sources of air pollution in southwest Indiana are five located in Warrick and Posey counties, which have no air quality monitors whatsoever. The monitors that do exist in the region, meanwhile, often seem to be located far from the sources of the pollution they are apparently designed to monitor.

For instance, Duke Energy’s Gibson Station, which at 3,340 megawatts is one of the largest coal-fired power plants in the world, is located on the Wabash River, near the Illinois border, while the nearest air quality monitor is all the way over in Oakland City, 27 miles to the east. The Rockport Generating Station, a 2,600 megawatt facility, is located in the far south of Spencer County, on the Ohio River, while Spencer County’s air monitors are 22 miles to the north, in Dale. I can’t find a single monitor close to one of the region’s major polluters. What’s more, just 21 out of 92 counties in the state monitor for particulate matter. That seems odd, but it’s perfectly legal under EPA guidelines, as far as I can tell.

Kreilein has looked at the monitoring data as well, and she sees dark forces at work. As we drive back to the hospital she rails against Indiana’s environmental regulators and the Republican governors and legislators who she believes have twisted the agency into a tool of the coal industry. “There are people all over southern Indiana hurting because of these power plants, and the state’s policy of looking the other way,” she says.

It’s a view rejected by Keith Baugues, the Indiana air quality official, both in the Channel 13 investigative report and in blogs on air quality he has written for the Indiana Department of Environmental Management website since 2013. In the posts, he argues that Indiana is meeting its monitoring and enforcement responsibilities under federal law, and that a number of counties are now violating Clean Air Act standards only because of a recent tightening of EPA pollutant limits. He writes that the state’s air quality is steadily improving, just as it is throughout the rest of the country. “Air quality is the cleanest it has been since the 1970s,” he wrote this March.

In a post last September, however, Baugues did note that Indiana faced air quality challenges not faced by other states. “Indiana has an industrial economy,” he wrote. “The manufacturing businesses that operate here have to comply with tight air pollution controls. But even with well controlled sources, we will have more air pollution compared with states that have a lower percentage of industry.”

He also acknowledged that more research was needed on potential links between pollution and ailments such as asthma, cancer and autism. But challenges involving data collection and patient confidentiality made such research difficult. “My point is that there is not a lack of interest in making analyses that would help us determine whether certain chemicals are part of a health problem. . . .” he wrote. “This work just is not progressing as fast as it should.”

The last time I see Kreilein, we meet in Jasper, in a little park on the banks of the Patoka River. Jasper is a sort of archetypal small Midwestern city, full of ball fields and churches and strip malls; the historic stone courthouse has a big old clock at the top. It’s an industrious place and seems to be doing well. As I learn later, the unemployment rate in the county is 4.1 percent, the lowest in the whole state and well below the national average. There’s a bit of that industriousness in the air, which hits me when I step out of my car. That’s the smell of “turkey litter” from the thousands of turkeys that pass through and around town every day, on their way from confinement pens to the slaughterhouse.

Kreilein sits at a picnic table with several of the core members of Healthy Dubois County. There’s Rock Emmert, a high school English teacher who sports a natty, Clark Gable mustache and drives a Chevy Volt; Kris Lasher, a massage therapist and Saint Mary’s College graduate who sings in a folk group called Wild Mother; and Alec Kalla, a retiree in his 60s with a weathered face, a stern gaze and a gravelly voice that reminds me of Dirty Harry.

The most recent development on the biomass front is that Healthy Dubois County and the city of Jasper have agreed to walk away from their long, expensive court battle, with both sides paying their own legal bills. The settlement is basically a wash, as the lawsuit’s key allegation — that Jasper officials violated Indiana’s government transparency laws by holding off-the-books meetings with the Twisted Oak developer and his attorney — will forever remain unresolved.

At the very least, the lawsuit has given both sides a bruising civics lesson, one that can’t be learned in a high school or college classroom. We may celebrate our freedoms in the abstract, but when citizens attempt to exercise them in the real world the results can be messy. Kris Lasher tells me she felt mocked by the city as a loony extremist for speaking out against the biomass plant. She had never protested anything before, and the plant was going to be built within walking distance of where some of her relatives live. “We were all just concerned citizens,” she says. “Now we’re radicals.”

After chatting for a bit, we drive over to the old Jasper coal power plant, which the city all but shut down in 2010. It’s a boxy structure of green steel and concrete, with a single tall smokestack. It was built in 1968 and strikes me as a well-preserved technological relic of that era, like a vintage turntable. It also occurs to me how much the attitudes that prevailed at the time of its construction have moved on. Rows of neat suburban houses sit just a few hundred feet away; as I climb into my car to leave, a mother with a newborn baby in her arms steps out of one.

The last stop of the night is a regularly scheduled meeting of the Jasper Utility Services Board, down at city hall. Nothing of particular interest is expected to happen, Kreilein tells me; the biomass plant might not be mentioned at all. But I want to go anyway.

That’s a good call, because the April 21st meeting turns out to be the swan song of the Jasper biomass project, at least for a good long while. Halfway into the meeting, Bill Kaiser, a private attorney who represented the city all through the protracted litigation with Healthy Dubois County, reads a letter from the president of Twisted Oak. The gist of the letter is that after three years, and a million dollars spent by the city on legal fees, consultants and other costs, the company is walking away from the project because it no longer makes economic sense. Wayne Schuetter, the chairman of the utilities board, looks like he just bit into a lemon. Kreilein stands against the back wall, arms folded, trying hard not to smirk. A few minutes later she walks over and whispers in my ear. “Wow, wow, wow,” she says. “This is it. It’s dead.”

The board moves on to other business. When the meeting finally drags to a close about 45 minutes later, the room takes on a fevered atmosphere, reminiscent of the aftermath of a bitterly contested high school football game. Alec Kalla stands up and sarcastically applauds the utility board. “I salute you,” he growls. “Good work.”

The small gaggle of local reporters in the press box seems gratified that something newsworthy has happened; one headline the next day will note that the biomass lease was “terminated.” They pepper the utility board with questions for about 20 minutes. “Don’t you feel that this is a setback for you?” Candy Neal, a reporter for the Dubois County Herald, asks a grim-faced Schuetter. “I mean, you’ve worked so hard on this.”

Outside city hall, Kreilein looks elated, as does her husband, Mike. “The last three years, it’s just been major stress. It got to be a real strain,” he tells me. “I feel great. I hope she feels great. This is a lot of weight off our shoulders.”

Later, in a wide-ranging phone interview, Schuetter and Hauersperger offer a spirited defense of the biomass project and are reluctant to recognize any of the shortcomings that led to its demise. “This was going to be one of the largest outside investments in Jasper in a long time,” Schuetter says. “It was a big deal.”

After some persistent questioning, they acknowledge that the project, which envisioned trucking in and burning 500 tons of miscanthus daily, would have impacted local air quality. Hauersperger tells me the projected emissions were equivalent to 50 fireplaces burning 24 hours a day. “The city council felt like that wasn’t that bad a range,” he says.

I mention that Dubois County already has air quality issues from local manufacturing and the large coal-fired power plants in surrounding counties. According to the state, the county has the highest levels of fine particle matter pollution in all of southwest Indiana. But Hauersperger says he and other city officials studied the data and found nothing troubling about adding another emissions source; they have families too, he adds.

“Our kids are growing up here,” he says. “Would we really do something that would be detrimental to their health?”

It’s a good question. Society and science do not stand still, and what was considered safe and acceptable in the past may come to be seen as dangerous and indefensible; smoking and seatbelts are good examples. The air is getting cleaner all over the United States — thanks often to impassioned citizen activism trumping the objections of industry and its allies in government. At the same time, advances in science continue to reveal the dangers of even low levels of toxic pollution. The result is a constant tension between economic interests and public health that will probably never be resolved to anyone’s satisfaction.

Norma Kreilein’s answer is that the status quo is just not good enough. So with the Jasper biomass plant dead in the water, she is now pouring her energy into the far larger and more complex issue of air quality all across Indiana. It’s a stage she will share with many other accomplished activists, some active for decades, and with considerable victories under their belts. But she is attacking it with her special fervor, writing endless emails, seeking meetings with state leaders and building a network of like-minded souls. Her major focus for now is on improving the state’s air quality monitoring network, which seems an achievable goal.

“There’s a huge problem,” she says, “and until we try to actually monitor and study it, the denial will continue.”

John Rudolf is a freelance writer based in Portland, Maine.