Photographs via University of Notre Dame Archives

Photographs via University of Notre Dame Archives

Editor’s Note: Rev. John Augustine Zahm, CSC, died 100 years ago. His visionary contributions to the evolution of Notre Dame into the academic institution we know today will be celebrated during this year’s Founders’ Day commemoration. This Magazine Classic from 2018 explores the legacy of Zahm, who faced criticism for his view of science and faith as complementary paths toward fulfilling the University’s ambitions.

Teddy Roosevelt lay nearly dead on the bank of an unexplored river deep in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. It was 1914, and the Bull Moose had malaria, a raging fever and a badly infected leg wound. His field cot sat in the mud, unprotected from rain or biting insects — not to mention cannibal natives — and impossibly far from hope.

Roosevelt held a lethal capsule of morphine in his hand, intending to spare his exploration party, which had already lost several canoes and one life, from the burden of hauling him through the jungle. Falling in and out of delirium, the former U.S. president kept repeating the opening line from a poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge: “In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure-dome decree.”

Roosevelt’s son Kermit knew his father well and told him he refused to leave his body in the Amazon if the elder Roosevelt died. Convinced that he’d be a greater burden dead than alive, TR rallied. But the perils of the expedition continued. Of the 22 Brazilians and Americans who had started down the infamous River of Doubt, only 19 would limp out of the jungle two months later.

The man who had launched this daring expedition was not among them. Rev. John Augustine Zahm, CSC, a friend of Roosevelt’s and a former vice president of the University of Notre Dame, had convinced the Rough Rider to travel to South America, then supervised the outfitting of the trip. But Roosevelt — at 55, the younger of the two men by seven years — later insisted on a more dangerous journey than Zahm had planned. Having reached the end of a two-month trek deep into the Brazilian jungle just to reach the known source of the uncharted river, Roosevelt deemed Zahm too old for the difficult final leg — the descent by canoe toward the Amazon River itself.

Chronicled in Candice Millard’s excellent 2005 bestseller, The River of Doubt, the tale of the ill-fated Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific Expedition is but one of many extraordinary stories involving Zahm, possibly the least known of Notre Dame’s early founding fathers. Yet in his prime, Zahm was a renowned scientist, academic and explorer, a man of broad interests and deep insight, far ahead of his time.

In 1913, Zahm wrote a book about women’s contributions to science — seven years before the United States considered women worthy of voting rights. His forays into the relationship between religion and evolution, which he did not find in conflict, culminated in a book essentially banned by the Vatican at the time, though the ideas he advocated would soon be recognized as accepted doctrine. His intrepid explorations of South America produced a trilogy of widely read travelogues.

Zahm’s contributions to Notre Dame’s transformation from a backwoods boarding school to a research institution of higher learning can hardly be overstated. He recruited the first international students, chartering special train cars to transport new pupils from as far away as Chihuahua and Mexico City. Besides pushing for separate campus buildings for science and engineering, he singlehandedly pioneered the creation of a theological seminary in Washington, D.C., that would train future generations of Holy Cross priests to become respected academics.

“Father [Edward] Sorin and the early brothers were the first founders of Notre Dame, and some have called Father [Theodore] Hesburgh the second founder,” says Father Thomas Blantz, CSC, a historian at work on a book about Notre Dame. “If so, might Father Zahm deserve some credit also? Maybe something in between — maybe a one-point-five founder of the University — for seeing Notre Dame’s potential that early, for laying some important groundwork for it and for nudging it along to the full university status that it enjoys today?”

Scientist

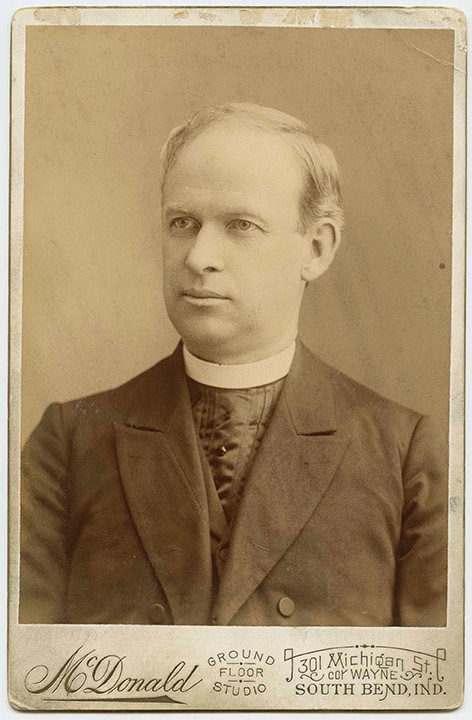

After his ordination in 1875, Zahm became a chemistry and physics teacher, an incidental academic appointment that would have an enormous impact on both Zahm and Notre Dame. His early interest and training was in Greek and Latin. The teaching appointment was a matter of the school’s need, not of Zahm’s preparation.

Born in 1851, the second of 14 children, he grew up in New Lexington, Ohio. He arrived at Notre Dame after helping his family collect the harvest in 1867, when tuition, room, board and books were $150 a year. He graduated four years later and entered the Congregation of Holy Cross.

The young priest threw himself into science with his trademark zeal. He began East Coast summer tours to buy the latest equipment, learn the latest research and build a specimen collection, using these assets to launch a popular demonstration lecture series.

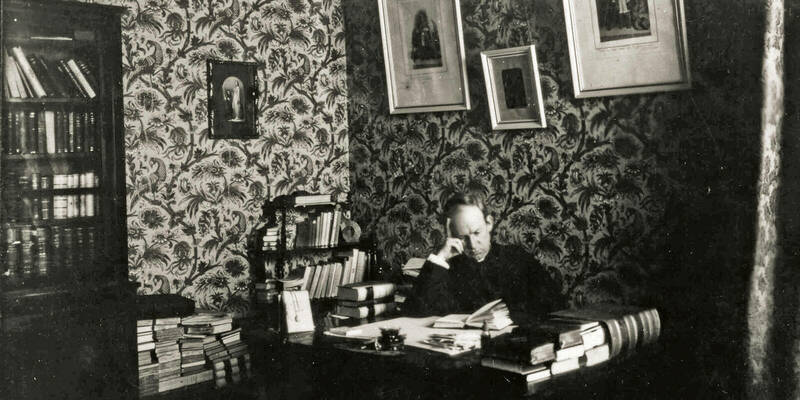

Zahm was not only a professor and explorer but he also gathered museum pieces and wrote about women in science and about evolution and faith.

Zahm was not only a professor and explorer but he also gathered museum pieces and wrote about women in science and about evolution and faith.

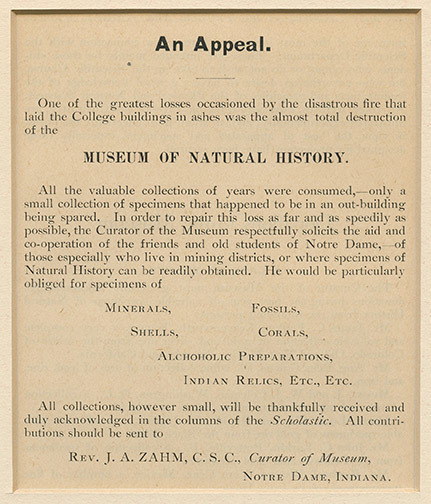

All was lost in the Great Fire of 1879 that burned down the Main Building. Zahm raced to restore what he’d lost and to lead the fundraising for a new stand-alone Science Hall, now the LaFortune Student Center.

One of Zahm’s innovative acquisitions was an electrical generator he purchased in 1881 to power a campus system of arc lights. Young cadets on campus used the curiosity to drill at night and to play football. Zahm soon used it to light Mary’s crown atop the Main Building’s new golden dome. Newspapers like the Ypsilanti Sentinel took notice, while revealing a common bias of the time: “It seems to us that the learned gentlemen at Notre Dame are making scientific advancement pretty rapidly for people who are supposed to live mainly in the mists of the middle ages.”

Not long after the University replaced the arc system with Thomas Edison’s incandescent light in 1885, a trade magazine credited Notre Dame as the country’s first college with electric light. Zahm, not gregarious by nature, learned to value such publicity, writing to his brother Albert, then a Notre Dame engineering professor: “Keep yourself before the public always — if you wish the public to remember you or do anything for you.”

Albert, 11 years younger than John, was destined to become one of the founding fathers of American aviation. In those early days, the two prodigious brothers turned westward for trips to collect specimens of minerals, animals and bones. Later voyages took Father Zahm to Mexico, Alaska and Hawaii, where he wrote newspaper reports exhibiting a viewpoint unusual for his day — real empathy for the natives, as well as arguments against cultural stereotypes that led to discrimination. His legendary vigor was on display in one report from his 1887 trip to the Holy Land with Father Sorin. Zahm rode alone on an Arabian pony to visit the Dead Sea, completing a journey that usually took four days in just 30 hours.

His fame as a scholar began in 1892 with the publication of Sound and Music, a scientific study of acoustics and the physical basis for musical harmony. He demonstrated his theories in lectures at the new Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., using musical instruments and sound apparatus from Paris.

By then, Zahm had already begun writing about the most important scientific topic of the era: evolution. Over the next four years, he would become the leading scientific apologist in the U.S. for the Catholic Church, joining other science-friendly Catholics who argued that evolution theory need not be in conflict with belief in God’s creation. During that frenetic span, Zahm lectured often and wrote five books, four pamphlets and 21 articles on the subject.

He wrote Albert of his first lecture series, “Didn’t I stir up the bears?” The priest tackled such topics as the scale of the biblical flood, the true age of humankind and “The Simian Origin of Man.” He preferred to understand and incorporate new discoveries and theories, rather than oppose them and suffer an embarrassment later — as the Church had done with the Copernican revision of the solar system, in which the Earth revolves around the sun and mankind is not the center of the universe.

Zahm said that the new science had strong evidence to support it, arguing further in the matter of Charles Darwin’s theories that “there is nothing in evolution, properly understood, which is contrary to Church doctrine.” Like some other theistic evolutionists of the time, he wrote that man’s body could have descended from apes, and that would not stop his soul from being created by God. He said theologians like Saints Augustine and Thomas Aquinas hadn’t contradicted the notion of God primarily setting the process in motion.

Some newspaper reports sensationalized his lectures. Headlines questioned whether Zahm was a heretic. The Catholic World took a more thoughtful approach, describing him as just what “intelligent and inquiring Catholics need, namely, a guide who can be trusted as safe, so that they need not fear to be led astray from faith and orthodoxy.”

His most controversial book, Evolution and Dogma, published in 1896, collected his studies on evolution. He wrote one critic: “My object is not to prove that the theories discussed are true, but that they are tenable, that they are not the great bug-bear they are sometimes declared to be. I wish to show that Catholics have no cause for alarm even should certain theories by which modern scientists set such store be proved to be true.”

In one interview, he predicted, “The twentieth century will not be very old before nine out of every ten thinkers and students will be evolutionists, as opposed to believers in a special creation.”

He became famous enough that the elderly William Gladstone, who had served as Britain’s Prime Minister four times, wrote him a postcard. “Theology has been for some time under the hand of intimidation which it is time to shake off, and I rejoice to see you occupying a forward place in this healthful process,” Gladstone opined, before echoing Zahm’s view. “Evolution, as I think, tends to elevate and not to depress the Gospel.”

Some critics expected Pope Leo XIII, who had given him an honorary doctorate in philosophy the previous year, to discipline Zahm when he arrived in Rome as procurator general of the congregation. Instead, he was well received — at first. But when his book was translated into French and Italian, the Vatican tide turned against him, catching him up in a larger ecclesiastical dispute known as Americanism, in which some American clergy accepted the separation of church and state in a way that displeased the Vatican — then embroiled in its own battles over temporal power with Italy. Zahm acquiesced to an official prohibition of his work in 1898 while his powerful friends kept a formal decree from being published, which would have been a blow to his reputation and career. Still, the Church’s stance ended his writings on evolution.

Zahm’s position prevailed.

Remembering his mentor in The Catholic World after Zahm’s death in 1921, Father John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, a former University president, wrote, “Father Zahm had the serene satisfaction before his life closed of finding the views he so courageously and clearly defended, accepted as the commonplaces of Catholic controversy by many of the same school of apologists who hurled theological brickbats at his devoted head a quarter century ago.”

Academic

The 1898 General Chapter meeting of the Congregation of Holy Cross marked the zenith of Zahm’s arc as a builder of the future Notre Dame. His appointment as the community’s U.S. provincial was formalized in election, opening the way for him to rescue the endangered House of Studies he’d established in Washington, D.C., three years earlier and to build a permanent facility to educate the young Holy Cross priests who would lead the school’s transformation.

Zahm did not stop to celebrate. He raced to Washington to buy land near Catholic University before real estate brokers heard about the decision and raised land prices. He was able to buy 4 ½ acres for $16,000 and oversee the building’s completion within a year.

The establishment of the D.C. house as Holy Cross College settled a pivotal conflict that had begun years before with Zahm’s appointment to teach science. Though chartered as a university in 1844, Notre Dame was still more of a boarding elementary and high school with a few college students. The congregation would assign its young religious to teach based on the needs of the moment, unwilling or unable to spare them the time or expense to acquire specialized subject knowledge. Some of Zahm’s powerful contemporaries, especially Fathers William Corby, Thomas Walsh and Andrew Morrissey, Zahm’s leading rival, believed that the school should continue to train its own teachers on the job and deploy them as needed.

Zahm disagreed. He wanted Notre Dame to become the intellectual center of the West, and that required specialized knowledge and research. He told his brother Albert, a layman, to build the best engineering department in the nation. “Our intention is to not simply equal Cornell, but to eclipse it both in buildings and equipment,” he wrote.

Father Zahm was relentless in his pursuit of funds and students to make this vision possible. He often returned from specimen collection trips with new students in tow, including the University’s first international cohort, chartering train cars to bring them to South Bend. Fourteen new students traveled nearly 2,000 miles from Chihuahua in 1883. They watched the landscape go by, sang songs and ate meals on board, picking up more students in New Mexico and meeting another student train car from Denver in Illinois. A banner on the side served as a traveling advertisement for the University. Alumni and friends greeted them at stations along the route. By 1887, two years after Walsh made Zahm vice president, his western trains were providing more than 15 percent of Notre Dame’s student population.

Zahm chartered train cars to bring students from Mexico.

Zahm chartered train cars to bring students from Mexico.

Another of his triumphs during this period was Sorin Hall, the country’s first Catholic dorm with single-study bedrooms. Until its completion in 1888, students typically slept barracks-style in large rooms of the Main Building. Zahm felt private rooms encouraged excellence, but Father Walsh, the president, rejected his subordinate’s idea. So Zahm turned instead to Sorin, who as Holy Cross’ superior general sent Walsh to a conference in Europe for two months in 1888. It’s not clear whether Sorin sent Walsh away specifically to allow the project, but Zahm had the building designed during Walsh’s absence. The cornerstone was blessed two days before Walsh returned as part of the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Sorin’s ordination. At the unveiling, Sorin learned the building would be named after him, ensuring protection for its future.

“I love to see in our Notre Dame of today the promise of the potency of a Padua or a Bologna, a Bonn or a Heidelberg, an Oxford or a Cambridge, a Salamanca or a Valladolid,” Zahm said at the ceremony. “It may be that this view will be regarded as proceeding from my own enthusiasm, but it matters not. I consider it to be a compliment to be called an enthusiast. Turn over the pages of history and you will find that all those who have left a name and a fame have been enthusiasts.”

As provincial, Zahm’s efforts moved beyond the construction of buildings to focus on what happened inside them. He recast graduate education on the German model, in which students conduct original research as a primary learning tool rather than receiving tutorials from faculty members. He added liberally to the campus art gallery and library, amassing a 3,000-volume Dante collection that today ranks among the best in North America.

The conflict over Notre Dame’s direction came to a head in 1906, when Zahm’s position as provincial came up for renewal. He spoke against stagnation, advising the superior general, Father Gilbert Français, CSC, that “we must give continual and striking indication of progress.”

“Notre Dame shall soon, like some of the great intellectual centers of the Church’s past, be also a recognized home of saints and scholars,” Zahm wrote.

His constant activity and mounting debts spurred his critics, including Father Morrissey, who had reluctantly stepped down from the presidency the year before, and who convinced Français that he should replace Zahm as provincial. Crushed, and so exhausted that doctors said he needed two years’ rest and foreign travel, Zahm left Notre Dame, never to return.

By then, Zahm’s younger allies were emerging as serious scholars and leaders. One protégé, Father John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, had replaced Morrissey as president. Another, Father James Burns, CSC, would succeed Cavanaugh. A third, the pioneering chemist and botanist Father Julius Nieuwland, CSC, later emerged as the community’s greatest priest-scientist. Such men would lead the transformation.

Zahm may be less well known today because he never became president, as biographer Ralph Weber and other admirers have speculated. But his impact was clear to his successors.

“I regard Father Zahm as the greatest mind produced by the University in its long career, and perhaps the greatest man in all respects developed within the Congregation of the Holy Cross since its foundation,” Cavanaugh wrote in his 1922 eulogy. “Maybe Father Zahm could not have laid the foundation of Notre Dame, but undoubtedly Father Sorin could never have built upon it as Father Zahm did.”

Explorer

Zahm embarked on a year-long tour of South America in 1907. Returning to Holy Cross College in D.C., he wrote two travelogues marked by their well-researched history and trenchant cultural observations. The first, Up the Orinoco and Down the Magdalena, caught the attention of Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote an introduction for the second, Along the Andes and Down the Amazon. They were published in 1910 and 1911 under the pen name Dr. H.J. Mozans, a loose anagram of John Zahm.

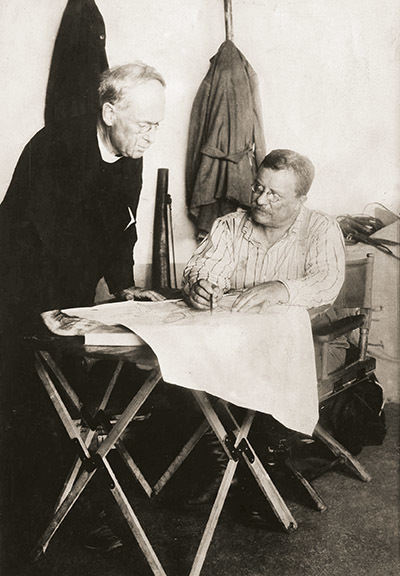

Roosevelt was a famed adventurer and a Dante fan, so the two men exchanged letters and spent time together telling stories. Zahm had asked Roosevelt in 1908 to accompany him on a return to South America after Roosevelt’s last year in office. The former president instead went on a hunting trip in Africa. But when Roosevelt lost his 1912 bid to return to the White House, he accepted the priest’s second invitation. Zahm appreciated his brush with fame, writing to Albert that he and Roosevelt were the “chummiest of chums,” and he valued the publicity the trip would gain. Roosevelt warmly described Zahm in a letter to a friend as “a funny little Catholic priest.”

Dozens of newspaper clippings in Notre Dame’s archives document the Amazon trip, an expedition of evolving scale and purpose partly funded by the American Museum of Natural History to collect biological specimens. “’Twas Father Zahm Who Induced Him to Explore in South America,” read the subhead of a story in The New York Times. “The friendship between the priest . . . and the ex-President is said to be primarily due to the their liking for pioneering,” the reporter explained, “but their intimacy goes back to the time Roosevelt occupied the White House, when he and Dr. Zahm spent many an hour chuckling over what they might do to natural history if they had only the time for it.”

Zahm took charge of planning the expedition, while Roosevelt added his own schedule of speeches and receptions across the continent. Having counseled Zahm to plan with caution, he returned to form and changed Zahm’s arrangements, opting for a more challenging journey down the uncharted River of Doubt when Brazilian authorities offered him the services of the renowned Amazon explorer, Colonel Cândido Rondon. The changes caught Zahm unprepared. He had not planned the right food or equipment for this kind of trip.

During Roosevelt’s two-month speaking tour of Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile and Paraguay, the unusual pair presented themselves to South Americans as a symbol of the friendship possible between a Catholic and a Protestant. The expedition itself began on December 12, 1913. Traveling 400 miles by foot and by mule to the headwaters of the River of Doubt as provisions ran low proved difficult enough, and the 62-year-old priest struggled to keep up during the 11-week trek. TR decided to trim the exploration party before descending the river, which the expedition soon renamed in his honor, and Zahm would return to the U.S. alone and without the place he desired in the tradition of great missionary explorers. But he got another book — Through South America’s Southland — out of the adventure, presenting the history, culture and Catholicity of the continent to a U.S. audience and completing his South American trilogy.

Roosevelt published his own account of the expedition, and the two men remained friends. The Bull Moose had returned home 60 pounds lighter but triumphant over the critics who had doubted his latest adventure. But the damage to his health was permanent, and he would write to his son before his death in 1919 that his ailment stemmed from his “old Brazilian trouble.”

Plenty of mystery surrounds Zahm’s whereabouts and finances in his later years. Though he had made enemies, it’s not clear why he shielded his activities. He was known to have friends postmark letters from places far from their origin, and he instructed Albert never to betray his location. His friend Charles Schwab, a steel magnate, supported his travels.

During this time, Zahm wrote two books that reveal a respect for women’s intellect and passion for their higher education, views uncommon in that era. The first book, Woman in Science, described the struggle of women for educational opportunities from ancient Greece up to the suffragette movement, predicting its coming victory. A second book, Great Inspirers, focused on the example of Dante’s beloved Beatrice in the Divine Comedy, as well as the monastic women to whom St. Jerome dedicated his Latin translation of the Bible.

His final book was a study of the Holy Land. As usual, the work reflected thorough research into the area’s history and the relevant science, and it offered a sympathetic treatment of the Muslim faith of the Ottoman Turks who had governed the region for centuries. Traveling there to gather local color and finish the book, the 70-year-old priest developed pneumonia in Munich and died on Nov. 10, 1921. His body was returned to Notre Dame, where he is buried in Holy Cross Cemetery alongside Sorin and the other great builders of the University. The unfinished book was published posthumously as From Berlin to Baghdad and Babylon.

Zahm’s vision and enthusiasm lived on. Like most prophets, the farm boy turned priest and scholar can best be appreciated in hindsight. His 1913 letter to Father Matthew Schumacher, one of the original Holy Cross College graduates who was then serving as the University’s director of studies, laid out a blueprint for the continuing physical and intellectual expansion of the University — a new library, academic buildings and dorms, but above all the advanced training required by a modern university entering “an age of specialists.”

“His plans are so great and expansive and his energy so intense, that each improvement only opens up a prospect for another and a greater one,” Father Burns once wrote. “Father Zahm will never be understood nor his work appreciated by this generation. He is too far in advance of the men among whom he is living.”

Brendan O’Shaughnessy works in communications for Notre Dame. A former teacher and Indianapolis Star journalist, he is the co-author of three Notre Dame books for children.