We met at the tail end of a most epic of Boston winters. The hopefulness that those March winds carried buoyed my steps across the parking lot. “Spring is around the corner,” I told myself optimistically. “All will be well.”

I checked in with the front desk and showed myself to the elevator. Knowing that I probably would be standing during our meeting, I left my briefcase in the car and carried only a small file. As it had been a busy day, I used the elevator ride to glance at the basic contact information of my client: date of birth, weight, name of treating physician. I made a mental note to inquire of my client’s first name, as none had been listed. The elevator doors opened.

“He’s right over there,” the receptionist directed after buzzing me into the neonatal intensive care unit. Other than that familiar hospital soundtrack of persistent beeping, the unit was quiet as I walked toward my client’s incubator. I passed mothers and fathers holding on to the smallest of hands — concern draping their soft caresses. I saw others nodding off in chairs as their young ones slept nearby. Nurses and doctors traded banter as they deftly cared for their tiny patients.

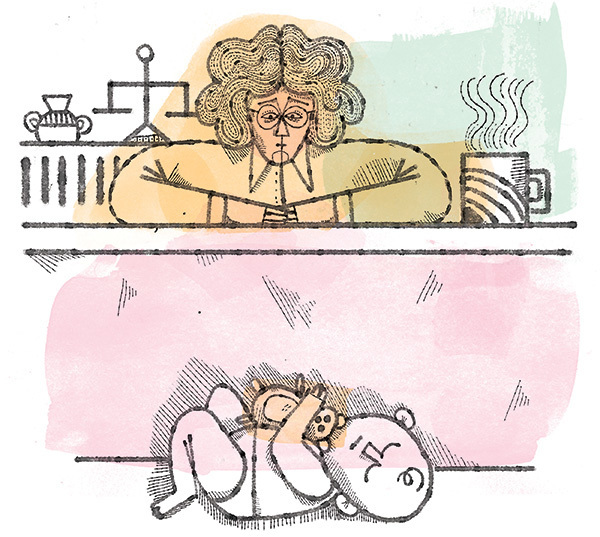

“Hi, I’m your lawyer,” I said softly as I peeked at my 15-day-old client.

“Here, I’ll pick him up so that you can get a better look at him,” came a cheerful voice. Soon, my little guy was cradled in the arms of his nurse, all 5 pounds of him practically disappearing into the folds of her colorful scrubs.

“His doctor will be here any minute, and we can talk,” the nurse offered.

“That would be great,” I said. “Oh, and what’s his name?”

“He doesn’t have one,” she replied. “His mother refused to fill out the birth certificate.”

“Are you serious?” I asked.

“I’m serious,” the nurse answered. “She hasn’t been back.”

The treating physician soon greeted us. “The worst that I have ever seen,” the doctor said, referring to my client’s withdrawal symptoms. “Horrendous,” he stressed. We stood close, sentinels joined by an unspoken union. “Throwing up, shaking uncontrollably, crying incessantly, rubbing his chin, a worrisome temp . . .”

I wrote everything on my legal pad as the doctor tutored me in the relentless scourge of withdrawal. We discussed morphine, phenobarbital, setbacks and progress as we unconsciously touched his cheek, stroked his little leg or held his hand.

I left armed with sufficient information to represent my client in the next day’s temporary custody hearing. I reviewed the irrefutable facts as I walked back to my car: heroin use 24 hours prior to birth, no prenatal care, 37 weeks gestation, high neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) score, GI work-up ordered. As I drove toward the hospital’s exit, my thoughts were interrupted by one most salient of facts: He has no name. Soon I was crying. Really crying. Though all too familiar with these cases in my many years as an attorney, the stark absence of a name was unbearable.

I thought about him in his little crib, oblivious to the glaring emptiness of his new life. Conversely, I was acutely aware of all that was missing. Sure, he was surviving right now because of the attentive care of his medical team. But I wanted him to thrive. We had just met, and still I wanted him to be cherished, to be claimed. I had a stake in this, after all.

I knew the temporary custody hearing would be a slam-dunk. If the parents appeared and there were a hearing, they would most certainly lose at this stage of the process. The facts were stacked against them: They had long histories of substance abuse, and they had a baby boy currently hospitalized. Significantly, they had lost custody of two other children, who were now free for adoption. They were also homeless. The Massachusetts Department of Children and Families (DCF) would need to establish a mere preponderance of the evidence — in other words, to show it is more likely than not that my client would be at risk for abuse and neglect should he return to his parents. The parents, however, could waive their right to the temporary custody hearing and agree to work closely with the DCF, with the goal of one day regaining custody.

Fueled by my experience at the hospital and by the knowledge that my client is one of more than 2,000 substance-exposed newborns reported to the Massachusetts DCF in the last year alone, I entered the courtroom equipped. The case was called as “The Babyboy M” matter. Surprisingly, the parents showed up. They sat in the back of the courtroom, standing only when the judge addressed them. Their attorneys informed the court that they would be waiving their right to the hearing. The parents promised to get into treatment and work with the DCF. The social worker urged them to return to the hospital and fill out the birth certificate. The DCF attorney and I argued for pretrial and trial dates within an atypically short time frame. As we exited the courtroom, I observed the mother laughing.

Days came and went without the parents returning to the hospital to name their son, sign the birth certificate or make any contact with the social worker. Many weeks later, with the baby still on phenobarbital, the social worker called to tell me my little client was finally ready for discharge. “He is being placed in the pre-adoptive home of his brother and sister. You are going to love this family,” she assured me.

By late spring, I was sitting at the kitchen table with Kate, the foster mother. This time I got to hold my 3-month-old client, his bright blue eyes peeking at me beneath little tufts of auburn hair. Dressed in a colorful onesie and sleeping comfortably in my arms, he was clearly “home.” Replacing the hospital soundtrack were the giggles and squeals of two toddlers and a preschooler playing. Two other children were on their way out the door with their grandmother on an adventure. I exhaled gratefully as I took in the scene.

“He is 9 pounds, 2 ounces,” Kate said proudly. Her broad smile masked any hints of fatigue as she added, “He’s up every two hours. He’s still tense, continues to spit up and have tremors.”She glowed as she spoke of his weight gain, his smile, his sweet disposition. She shared the emptiness she feels every time she is at the doctor’s office with him and the receptionist calls out, “Babyboy M!”

Kate told me that she is a nurse and her husband is trained as an emergency medical technician. Together they wanted to open their home to children in need. After welcoming their only biological child, a daughter, the two have gone on to foster and adopt five children. My client’s biological 4-year-old brother has been in the home since he was 18 months old. His 2-year-old sister has been in the home since her own hospital discharge. Both were born drug-addicted. They have finally been cleared for adoption. I asked Kate if she and her husband planned to adopt my client once he is free. “Absolutely,” she said without hesitation. “He is part of this family.”

Theirs is an educated and fierce commitment. Well-versed in the needs of substance-exposed newborns and how those needs follow children throughout their development, Kate and Tim have already teamed up with specialists at Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital. They have enlisted the state’s early intervention services to stay alert to my client’s milestones. They have no doubt that Babyboy M’s journey to their home is a “miracle.” They want to ensure that his life with them will be joyful. They look forward to naming him.

Tara Begley Wegener lives in Quincy, Massachusetts, with her husband, Bob Wegener ’80. She is the mother of three grown children. The names of the foster parents have been changed.