I’ve been in the Maycomb, Alabama, courthouse to see Atticus Finch defend Tom Robinson and deliver his plea for justice to an unmoved jury. This journey through time and space did not happen in the pages of To Kill a Mockingbird or its Hollywood portrayal — although I’ve taken those routes numerous times. This was a live and in-person kind of thing. Bob Ewell sat spitting distance away at the witness table.

Every spring Harper Lee’s hometown of Monroeville, Alabama, stages To Kill a Mockingbird to attract literary pilgrims. The first act takes place on the courthouse lawn, the second inside for the trial. It’s a moving experience to see the story come to life where reality merged with Lee’s literary imagination.

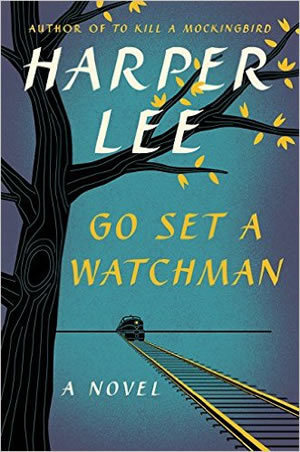

While I was in Monroeville last April, I pre-ordered Go Set a Watchman from the local bookstore. Browsing the Ol’ Curiosities & Book Shoppe, the sequel/first draft of dubious origin felt like a must-have despite my misgivings about whether it should have been published at all.

By the time it arrived, reviews already had revealed the racist recasting of Atticus Finch and established Watchman as a faint echo of its classic predecessor. Mine stayed on the shelf becoming a dusty souvenir, a must-have but not really a must-read.

I’ve since taken the trip back to Maycomb in its pages with the adult Jean Louise Finch, who’s visiting from New York and turns out to be outraged enough for everyone at her father’s ugly evolution. It’s debatable whether the reactionary attitudes of 72-year-old Atticus really represent an evolution from the hero we thought we knew, but the inevitable comparison just shows how hard it is to judge the new book on its own merits.

To the extent I can separate it, Go Set a Watchman does pale next to its predecessor. Told in the third-person, there are only infrequent flashes of Scout’s tart wit and lyrical insight that gave To Kill a Mockingbird such vivid life.

Set in 1950s Maycomb, it contains much hand-wringing and hollering about the overreaching Supreme Court and the intruding NAACP. There’s no plot to speak of, outside of a little will-they-or-won’t-they about Jean Louise and a suitor trying to win her hand in marriage.

Most of the book chronicles her revulsion at the discovery that her adored father has aligned himself with the local citizens’ council — the KKKiwanis club, so to speak. She experiences vomiting and other symptoms of the vapors.

After a spiteful fight with Atticus, who suffers her bitter recriminations with the same stoicism he did when Bob Ewell spit in his face, Jean Louise’s uncle susses out what’s gnawing at her. She’s always seen her father as a god, not a man. And there it is. So have we all.

Reading Go Set a Watchman forces a reconsideration of To Kill a Mockingbird. Not of its literary value but of the qualities that we, like Scout, projected onto Atticus beyond what his actions warranted.

Defending Tom Robinson required real strength of character in that time and place, but his true peers in town — the judge, the sheriff, Miss Maudie — expected it of him and respected him for just that quality. He couldn’t have said no.

And while Atticus protected his client from a lynch mob, he didn’t dare protest the preordained all-white jury that was, in effect, a legally sanctioned form of justice-by-noose. He might have gone above, but he did not go beyond the boundaries of a social structure he supported as a pillar.

In To Kill a Mockingbird Atticus believed Tom Robinson to be innocent and therefore deserving of acquittal, an enlightened position at the time. But he showed no signs of believing, for example, that Tom’s children should be allowed to attend Scout’s school, as the truant Ewells were welcome to do.

Considered that way, the Atticus of Go Set a Watchman seems more consistent with the man we knew — ahead of his time in the 1930s, but not nearly as far as Scout (or we) allowed ourselves to believe.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.