The bell tower of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart isn’t on the standard Notre Dame campus tour for good reason. It’s kind of a dangerous place. The wooden stairs are narrow and steeply pitched, and the first flight alone is sufficiently dusty and Hitchcockian as to discourage anyone but the most determined and cautious visitor. If you’re up there for a quarter hour or more, earplugs are a must. But the reward is an up-close view of St. Anthony of Padua, the church’s 6½-ton bourdon bell, as well as what is widely thought to be the oldest carillon in North America. And if you line up with a sunbeam and cock your head just right, you discover that the 23 carillon bells named for Mary speak for themselves: “I was blessed by the Rev. E. Sorin . . .” one inscription reads.

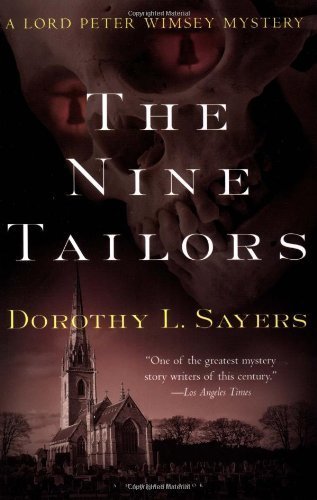

I was prepared to meet bells that have names and personalities thanks to The Nine Tailors, generally considered the best of the 11 detective novels Dorothy L. Sayers published in the 1920s and 30s. The tailors of the title don’t make garments. They are the bells of the fictional Fenchurch St. Paul, “tellers” of time and death for this lonely hamlet situated in the watery coastal lowlands northeast of London. Their names and inscriptions read like tombstones. “Abbot Thomas set me here and bade me ring both loud and clear,” says the second largest but oldest and most ominous of the bells. Cast in 1380, Batty Thomas is thought by locals to have struck one of Oliver Cromwell’s soldiers dead and later to have hanged an inexperienced bellringer in its ropes.

But it is a third, modern death in Fenchurch St. Paul that draws Sayers’ charming detective, Lord Peter Wimsey, back to the town where he had found himself helping to ring the bells for eight hours one New Year’s Eve. When the spring thaw comes, an unidentifiable body turns up buried in the gravesite of a local aristocratic family to which the corpse does not belong.

What the bells know about it, they aren’t telling. In the baffling investigation that follows — a Faulkernian telling and retelling of what might have happened, as mesmerizing as the sequential peals of the bells themselves — the same names keep turning up over and over again as either potential murderer or possible victim.

Wimsey’s devotion to the town, its people and the unfolding of the crime opens unexpected windows onto an English culture flailing to right itself after the lingering disruptions caused by the First World War. A friend warned me I might find the novel “a little dated” when she gave me her copy this summer. It was anything but. This is literary mystery perfect for the dialogue-devotees of Downton Abbey and Gosford Park. Sayers’ smart descriptions of peculiar English customs like change-ringing, and of the arcane engineering marvels that for centuries kept her East Anglia from drowning in annual spring floods, sparkle every bit as much as the affectionate portraits she paints of her characters, even those with minor roles.

There is no condescension toward the rural or low-born here. Nor for Sayers’ readers. The plot, complex even by the standards of the genre, requires attentive reading. But then The Nine Tailors is the first novel in years I’ve allowed myself to read until 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning, when the world is just quiet enough to carry the voices of Sacred Heart’s bells from Sorin’s ancient tower to my bedroom window.

John Nagy is an associate editor of Notre Dame Magazine.