Illustrations by James O’Brien

Illustrations by James O’Brien

Editor’s Note: It’s back-to-school season, but there’s no summer break in the perpetual debate about the quality of education offered to American children. Our latest Magazine Classic, from 20 summers ago, considers evidence from educators and researchers suggesting that policies designed to improve outcomes for public school students miss the key point — that academic failure starts at home.

Once upon a time there was a village with a bakery famous for its delicious pumpkin pies. The villagers took pride in their bakery, and rightly so. It really was their bakery. They owned it jointly, and the surrounding farms supplied all the pumpkins that went into the pies. People came from all around to buy the pies, and the village prospered.

One year, however, the area suffered a drought and the onset of a pumpkin blight. To everyone's relief, the farms were still able to produce enough pumpkins to keep the bakery supplied. But the pies tasted different, bland. Customers noticed the difference and stopped buying as many pies. This worried the villagers. They called a town meeting to discuss the crisis.

To most, the source of the problem seemed obvious: The bakers must be incompetent. It was suggested that each baker be tested on pie-making, and anyone who didn't pass be fired. This would prove a powerful incentive for the bakers to return to making good pies.

Others argued that the problem was low wages. If the average salary for bakers were raised, they said, it would attract better bakers who could make better-tasting pies.

Another faction insisted that a system of quality control would do the trick. Station a pie taster at the end of the production line. If the bakers know their pies will be tasted at random before they leave the bakery, they'll naturally produce uniformly delicious pies.

Still others insisted that the problem was the bakery itself. The building was old and drab. The village needed a new facility, with carpeting and skylights. One person said she had visited an attractive bakery in a far-away village recently that baked great pies. She said it used convection ovens. How, she asked, can we expect to make good pies without hi-tech equipment?

These were all good ideas, everyone agreed. And so, over time, they were all tried. But the flavor of the pies did not improve, and the villagers despaired.

A year passed and then another, and the public bakery was on the brink of bankruptcy. But in the third year, the rains came and the pumpkin blight abated. Something magical happened. The pies began to regain their old flavor. Prosperity returned.

In the months and years that followed, the people of the village speculated endlessly about what had caused the turnabout. Finally they determined that all of them had been right all along. It just took a while for their reforms to take effect.

As with this imaginary village, in the United States today we're having difficulty seeing the source of a problem. Only it's not in our bakeries, it's in our public schools.

During last year's presidential campaign, candidates of all parties touted plans for fixing our "failed" public schools. The solutions sounded like those suggested in Pieville: Boost salaries to attract better teachers. Institute national standards and tests to certify teacher competency. Require that students take standardized tests to make sure they're learning all they should. Upgrade school facilities and equipment, especially computers to close the "digital divide."

Others pushed for more charter schools or issuing vouchers to help greater numbers of families send their children to religious and other private schools, which are thought by many to teach better than public schools.

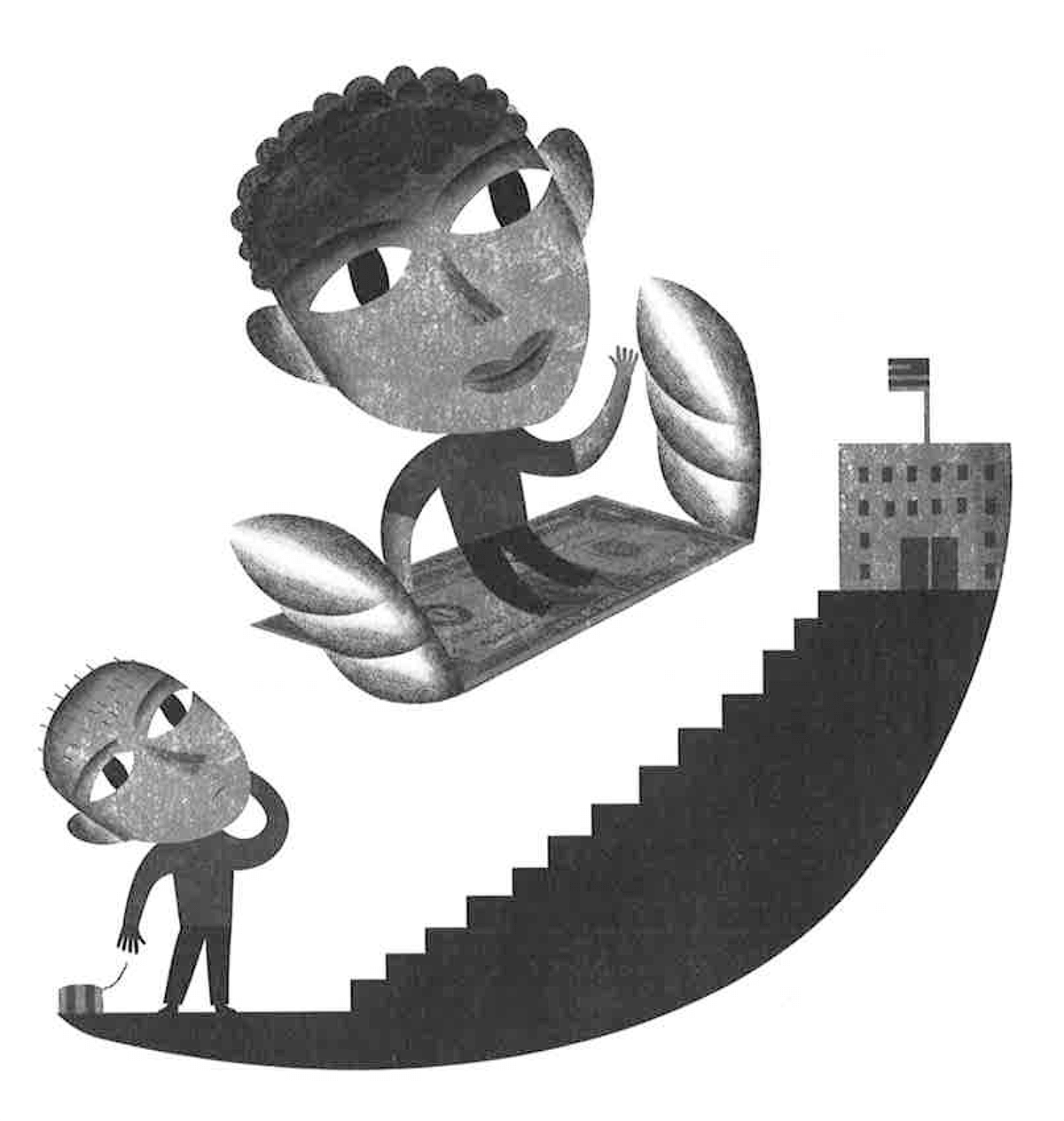

What no candidate dared suggest is that the problem isn't entirely the schools but the raw materials going into them: the students. Just as a bakery will find it difficult to make the same pie with different ingredients, schools given students of different backgrounds can see vastly different results in terms of academic achievement.

Although exceptions abound, study after study shows that children from low socioeconomic-status families generally achieve less academically than students from better-off families. A lot less. According to the federal Department of Education's 1998 Reading Report Card, the average low-income 12th grader in this country reads at the same level as the average middle-class 8th grader.

It appears to matter little how much your teacher is paid, how nicely your school is equipped, how often your state tests your competency. If your family tradition is low income and little education, you are likely to get less out of school than if you come from a middle- or upper-class background.

Education scholars have known this for years, but it's a tough reality for Americans to face — which makes it suicide for any national politician to acknowledge. The problem is that one of our most cherished national beliefs is in equality of opportunity. Most of us have no problem dealing with capitalism's inevitable unequal distribution of wealth, so long as everyone is given a fair shot at attaining that wealth. A free, quality education is supposed to be the equalizer of opportunity, the engine of social mobility.

Doubt begins to creep in when we see generation after generation of children who attend public schools in poor areas scoring lower on standardized tests than children in more affluent areas, or than kids going to private schools. Politicians tell us to blame the schools, that they aren't offering poor children the tools they need to lift themselves up out of poverty.

In reality, schools offer much the same curriculum whether they're next door to a Lexus dealership or a Goodwill thrift store. And differences that may have once existed are fast disappearing as educators are forced to "teach to the test" — drilling children until they can supply the requisite answers on state-mandated competency tests.

So while teacher quality may vary wildly from one classroom to another, students' exposure to the basic tools of reading, math and science may be more uniform than ever. The mystery is why students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds seem less able to master those tools.

Studies suggest that the main reasons are differences in home and neighborhood life. Some of the differences are obvious. There are neighborhoods so dangerous that children have been shot on the way to school for not knowing the right gang sign or for inadvertently wearing the wrong colors. There are families so poor they can barely afford clothing, shelter and food. Survival takes precedence over algebra homework.

Domestic violence occurs more often in families living in poverty, as does drug and alcohol abuse. Unwed teen mothers often lack prenatal care, and low birth weight is thought to affect a child's later ability to focus and learn. Pregnant women who take drugs or fall victim to violence increase the odds of their offspring having developmental problems.

"A lot of people are on drugs or alcohol and that's quite an issue," says Doris Porter, a parent and former president of the PTA at Lew Wallace High School in Gary, Indiana, near Chicago. A significant portion of the school's students come from poor families. "Sometimes these kids come out of homes where they don't see their parents but once a week and for some of them the only meals they get are in school."

No one should discount these real and immediate dangers. And obviously Internet-accessed computers and full refrigerators help children from more affluent households succeed. But something else lies behind the achievement gap: class values.

Class is a subject most Americans aren't comfortable talking about. We were all taught in social studies that in our society one's life course is not predetermined at birth. This isn't India; we don't have a caste system.

The other reason we're uncomfortable acknowledging class is that when we talk about class differences we inevitably begin to sound like we're talking about race differences. That's because class still correlates with race to a significant extent in our society. A larger share of African-American and Latino families have been poor for generations than have Caucasian or Asian families. So to suggest that families of generational poverty frequently have different values than families entrenched in the middle class — and that poor families' values don't mesh as well with school success — is to risk being called a racist.

One of the few people who's taken the risk is Ruby K. Payne. Her 1995 book Poverty: A Framework for Understanding and Working with Students and Adults from Poverty offers a forthright explanation of class value differences as they relate to education.

An educator since 1972, Payne gives dozens of talks each year to teachers and administrators. Her audiences typically are dominated by people from middle-class backgrounds who teach in schools serving poor neighborhoods. They often wonder how students can spend $30 on a Halloween costume or $400 on the prom but don't have the money to pay the book bill (an actual scenario described in promotional materials for Payne's conferences). Middle-class teachers also wonder why so many of their students from poverty lose papers, never have required signatures, don't do their homework and are physically aggressive. Are they just dumb?

Not according to Payne, whose husband grew up in poverty. In more than 25 years of marriage, she says, she has gotten to know the characters and dynamics of the old neighborhood. Payne says poor children have no less native intelligence than children from families better off financially. The difference comes from what she calls the "hidden rules" of class, the unspoken understandings of what is the preferred way to think, speak and interact.

One of the hidden rules of the middle class, she writes, is an emphasis on self-sufficiency. When middle-class people come into extra money they typically invest part of it for future security. In families of generational poverty (two generations or longer), any extra money is shared or immediately spent. The understanding is you'll never get ahead, so you might as well enjoy it now.

Payne says families in generational poverty value education as an abstract ideal; you'll often hear them say getting an education is important. But the hidden rules work against school success. Time is not seen as something to be valued or used, so being somewhere on time is not a priority. The emphasis is on current feelings, so if you don't like a boss or teacher, you just quit without thinking about the ramifications.

Perhaps the most obvious class difference is language. To succeed in school, Payne says, students have to use what's called "formal register," the standard sentence syntax and word choice of work and school. The ability to use formal register is a hidden rule of the middle class. The inability to use it can knock someone out of a job interview in two or three minutes and make college-level work impossible.

It doesn't take a genius to guess why so many children from generational poverty can't use formal register: No one around them uses it. In fact, a study carried out in the early 1980s at the University of Kansas found that in families where the parents were professionals, their 3-year-olds used more extensive vocabularies in daily interactions than did mothers on welfare.

If the achievement gap comes from cultural values, the question is whether schools can do anything to overcome those values.

Many conservatives and liberals alike think schools can, but that's only because they think schools are to blame for academic failure in the first place. During last year's presidential race, George W. Bush described children from poor families who were doing poorly in school as victims of the "soft bigotry of low expectations." Bush and allies call for higher standards, national testing and holding schools "accountable," which means rewarding those where children do well and penalizing those where they don't.

One reason they believe schools can overcome class-value obstacles in poorer communities is because it has been done. A favorite example is Jaime Escalante, model for the character played by Edward James Olmos in the movie Stand and Deliver. Escalante led large numbers of Mexican immigrant youth at a poor East Los Angeles high school to passing scores on advanced placement calculus tests.

One could also make a movie about Brother Bob Smith's accomplishments in Milwaukee. Fifteen years ago, Smith, then a 27-year-old African-American Capuchin friar with no prior experience in school administration, was asked by parents to take charge of the Catholic school where he was teaching, Messmer High School in Milwaukee's inner city.

Messmer was built to serve white ethnic parishioners, but by the 1980s most of the students were black, non-Catholic youth whose parents had trouble paying tuition. Faced with mounting deficits, the diocese decided to close the school.

Today Messmer is still open and — although decertified for a time by the diocese — still Catholic. It still serves students from its tough neighborhood, where more than half of the families live below the poverty line. But its academic results look more like those of an affluent suburban school. Ninety-five percent of students graduate, and most go on to college.

Milwaukee is one of only two cities, along with Cleveland, to have experimented with publicly funded school voucher programs, and some of Messmer's students attend the school using the assistance. Not surprisingly, Brother Bob, who now serves as president of the school and concentrates more on fund-raising, is a staunch supporter of voucher programs.

Smith says the socioeconomics of a student population don't have to trump achievement. According to him, the keys to serving disadvantaged populations are having administrators with vision, leadership skills, a sense of mission and high expectations, and people who are in it "for the kids and not money."

He's probably right about that formula. Experience shows that almost any kind of school reform works when it's carried out by teachers and administrators as able and dedicated as Smith and Escalante. The question is whether enough charismatic, gifted and dedicated teachers and administrators exist to operate every public school serving a poor neighborhood. Ninety percent of U.S. children still go to public schools.

The answer is, probably not. In fact, the opposite is closer to reality.

According to studies by sociologists Linda Darling-Hammond and Laura Post of Stanford University, the least qualified teachers typically end up in high-poverty schools, where the best teachers are most desperately needed. They say teachers consider it a promotion to move from a high-poverty to a middle-class school even if the pay is no better. They know there will be fewer discipline problems, among other pluses.

Comparing achievement in public schools against those of religious and other private schools ignores important differences in their missions, says Bill Carbonaro, assistant professor of sociology at Notre Dame and a fellow in the University's Institute for Educational Initiatives. As Carbonaro points out, public schools are required by law to educate all children, even those with special needs, even those whose class values may make them more difficult to educate. But private schools can choose whom they'll admit and can much more easily expel those who fail to live up to school standards — or whose parents fail to live up to their obligations.

One of those obligations, of course, is to pay a tuition bill, and the educational benefits of parents writing checks for school is often overlooked. As one Catholic who attended Catholic schools and now sends his own children to them, puts it: "I have curiously clear memories of 'I'm paying good money to send you to a Catholic school, so you damn well better pay attention and get those grades up.' "At public schools, you'll always have a percentage of the parents who are indifferent at best about their kid's education. That's got to make a big difference."

Backers of vouchers often say it's unfair that more-affluent families have a choice of where to send their children while poor families are stuck with whatever public school their children are assigned to.

They may have a point. Vouchers could provide a vital escape hatch for the motivated students trapped in a school dominated by disruptive kids, or a school where standards are set low out of fear that everyone would flunk out otherwise.

But voucher theory also assumes that children of poverty who are performing predictably sub-par would see the light if they got into a school where middle-class students and culture predominated. It's conceivable this would happen. Peer pressure can be a powerful force. But improvement-by-association has been tried, and most people judge it a failure.

It's called desegregation.

In its 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court struck down the concept of separate-but-equal as inherently unequal. Later, persuaded by research suggesting desegregation could help black children overcome the stigma of inferiority conferred by segregation, the government adopted a policy of racially integrating schools. Busing was designed to end the de facto segregation of neighborhood schools that results from people grouping themselves into neighborhoods by income level and ethnicity.

Remember, socioeconomic status correlates to a great extent with race and did so even more 30 years ago, when desegregation began. So busing provided a rough test of the effectiveness of moving concentrations of students from poorer backgrounds into proximity, at least on school days, with more middle-class kids.

Has it worked?

An urban public school district like South Bend provides evidence. At Clay High School, just north of Notre Dame on Juniper Road, most of the African Americans who attend are bused from the poorer inner city. The mainly white suburban kids ride in on separate buses with their neighbors. For the most part these groups remain socially and academically separate all day long. What's more, white parents see few black parents at the school's music or drama performances or other extracurricular programs.

Warren Outlaw, who is African-American, grew up in a poor area of west South Bend. He now directs Notre Dame's Educational Talent Search program, which seeks to identify and encourage potential first-generation college goers from among low-income families in the area. He also has had children attend the South Bend city schools. He says inner-city parents aren't more active in desegregated schools like Clay because they don't feel the schools belong to them. Not only are they physically separate from their neighborhood, but most of the children attending the schools aren't their neighbors.

Researchers say desegregation has helped close the achievement gap some between black and white children in urban areas. But the reduction has been so small that parents on both sides don't think the gain has been worth the disruption.

Carmel, Indiana, is an affluent suburb of Indianapolis. Driving south on U.S. 31, which bisects Indiana from top to bottom, you know you're getting close to Carmel, and money, when you pass the tasteful newer shopping centers clustered along the highway. Over the storefronts are names like Barnes and Noble, Bath & Body Works, Starbucks.

With 3,400 students, Carmel High School is the state's largest high school. It's also one of the most elaborate, with wide carpeted hallways, contemporary architecture and a multitiered media center (what used to be called a library) furnished with purple upholstered sectional seating and plants.

Carmel High School's enrollment is nearly 92 percent white with the largest minority being Asians (5 percent). Less than 2 percent of the students come from families poor enough to qualify for free lunches. Every year about 90 percent of sophomores pass both sections of the state's graduation qualifying exam, which is about 25 points better than the state average on the math portion and 20 points higher on the language arts portion.

Those figures are impressive, but are in fact no better than predicted by a formula used by the state's education department. The formula takes into account students' socioeconomic status along with cognitive skill (ability to learn), as measured by other tests.

Carmel High Principal William Duke, who previously headed a rural high school that underwent forced integration, acknowledges the importance of socioeconomic status when he says, "As much as I respect our staff, I believe they would be sufficiently challenged if we had a different population here."

Three mothers active in the Parent Teacher Organization say students at Carmel do well because parents have high expectations of their children and they stay involved. By involvement, they mean more than just helping their kids with homework. The Carmel PTO has 1,600 family members — so many that there's a waiting list to volunteer at school functions.

"I've had people call and complain that they've had their name in for three years and no one has called," says Ellen Modiano, who organizes an annual book sale at the junior high school.

Listening to Carmel's mothers, one gets the impression they believe families in generational poverty could beat the odds against their children succeeding in school if they adopted middle-class attitudes and behavior.

As elitist as that sounds, many experts and even parents from poor backgrounds agree.

Patricia Montgomery, who has taught physical education for 13 years at Lew Wallace High School in Gary and for 15 years before that in urban East Chicago and Houston, says her parents were poor immigrants from Panama. They didn't speak English when they arrived in the United States, but they knew what the letters on a report card meant.

"They made sure that I was fed and dressed everyday and made sure education was the number one thing in our lives every day. It was mandatory. You were not allowed to come home with Cs or Ds, let alone Fs," the teacher, who is African-American, says. "A lot of parents [here] just drop the kids off at school and never think about it after that."

Carbonaro, the Notre Dame sociologist, says 20 percent of students' achievement levels is due to differences in schools and 80 percent to the students' characteristics. But one reason children from middle-class families learn more at school is because their parents encourage the schools to teach them more.

He's studied the effect parental involvement has on "tracking," the practice of grouping students according to their ability in subjects like reading. High tracks move faster, low tracks slower, so students put on the lower tracks cover less material.

The lower a child's socioeconomic status, Carbonaro says, the more likely the child is to end up on a low track. That's not because of some conspiracy to keep poor people down. Poor students simply show less ability to learn from the start of their schooling.

However, even among students of equal demonstrated ability, students from higher socioeconomic status families are more likely to end up on the high tracks. Why? Parent involvement. He says middle class parents fight to get their kids exposed to the most challenging material because they understand it will pay off later.

"Low (socioeconomic status) parents . . . don't really know how the system works and how to work the system in their favor," he says.

But it isn't just parents working the system that pushes middle-class children ahead of poor ones in the early grades. Susan E. Mayer of the University of Chicago's Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies and author of the book What Money Can't Buy: Family Income and Children's Life Chances, reports that by age 6, low-income children are already the equivalent of nine months behind children from more affluent families in terms of cognitive growth. Another study found that the achievement gap between children in high poverty and low poverty schools starts at 27 percentage points in the first grade and grows to 43 by eighth grade.

Carbonaro says the early emergence of the gap results from a combination of what middle-class families are doing and what poorer families aren't. Because they believe education will give their kids a competitive edge in life, middle-class parents are motivated to do things like teach their children to read before they start school. They also seek out, and can afford, quality daycare and extra years of preschooling. Carbonaro's own children, he says, have been in preschool since age 2. "They'll have three more years of schooling when they reach kindergarten."

Studies show that the children least likely to attend preschool programs are those from low-income and single-parent families and those whose parents have the least education.

It's a continuing cycle and a game rigged by class values. All parents want their children to succeed, but only some understand how to improve the odds.

Before it became standard procedure politically to blame schools wherever low test scores appeared, people wondered if society could do anything to help poor children do better in school.

In the 1960s, as part of President Johnson's Great Society plan, the federal government launched a pair of programs with that aim, Head Start and Title I. Head Start is a preschool program. Title I grants money to schools serving large numbers of poor children to use as they see fit. Most use it to hire tutors for additional one-on-one instruction, usually in reading.

The programs, which have each consumed about $100 billion during their existence with billions more budgeted for this year, make sense in theory. In practice, they've disappointed. A 1995 study found no difference between children who attended Head Start preschool and their own siblings who did not attend. Likewise, a 1997 study found no difference in growth between students who were and were not tutored under Title I.

The likely problem with Head Start and Title I is that they try to fix the symptom of poor academic performance by throwing more schooling at children. They don't try to solve the underlying cultural disadvantages.

Other ideas have been suggested that might.

Ruby Payne says school is the only place children of poverty can learn middle-class values, so schools should teach these values — "not in denigration of [poor children's] own but rather as another set of rules that can be used if they so choose."

She also suggests schools reorganize so children can stay with the same teacher for three or more years. This would eliminate the time teachers invest at the beginning of the every school year establishing relationships with students and parents.

"When students who have been in poverty and have successfully made it into middle class are asked how they made the journey," Payne writes, "the answer nine times out of ten has to do with a relationship — a teacher, counselor or coach who made a suggestion or took an interest in them as individuals."

Some school districts have adopted a strategy of coercing or even intimidating parents into making sure their children perform in school. In one elementary school in southern Indiana parents are required to sign contracts promising to have their children prepared for school each day. In South Bend and other cities, juvenile court justices have the authority to jail students or parents or both if young offenders don't keep up with their school assignments. Since 1993, teachers at Chicago's Harold Washington Elementary School have been issuing parent report cards, grading parents based on whether their children submit homework on time, respect authority, follow dress codes and attend classes regularly.

Probably the most promising news about the potential for schools to overcome the achievement gap comes from a study by sociologists Doris Entwisle, Karl Alexander and Linda Steffel of Johns Hopkins University. In 1982 they began tracking children through the city schools in Baltimore. Their early findings were predictable and discouraging: Students from poor families were starting out way behind those from higher up the socioeconomic scale.

But a different picture took shape when they started giving children standardized tests at both the beginning as well as at the end of the school year. They found that the poorer first-graders started out at a lower level but actually acquired knowledge during the year as fast or faster than kids from more-affluent families. Over the summer, however, the children from the better-off neighborhoods continued to gain knowledge while those from poor neighborhoods stayed the same or fell back.

The sociologists call it the "faucet" theory: When school is in session, the resource faucet is turned on for all children, and they all gain equally. When school is out, the faucet is off, and different things happen in different households. Poor children, often in homes without daily newspapers, encyclopedias, computers and other educational resources, see their learning plateau. In the resource-rich middle-class households, cognitive growth continues, though at a slower pace than during the school year, they say.

The way to keep poor children from falling back over the summer while middle-class children creep ahead, the sociologists say, is to provide poor children high-quality preschooling so they can start first grade at an equal level. Then send them to summer school before and after first grade. The summer school should concentrate on reading, they say, but should also offer organized sports and other activities like the trips, visits to parks and museums, and organized sports that benefit middle-class kids during the summer.

Such a limited early intervention would suffice, they think, because reading achievement in their study improved twice as fast in grade one as in grade three — at age 6, children's cognitive development is proceeding at probably twice the rate it does two or three years later.

The researchers say the faucet theory shows that schools "are so effective that nothing else matters when they are open." Poor kids really don't have any less native intelligence. They learn just as fast as better-off children.

Now if they could only be kept in school all the time. . . .

Lew Wallace High School and Gary is about as far from Carmel and Carmel High School as you can be and still be in Indiana.

In the northeast corner of the state, near Chicago, Gary was founded by the steel industry early in the 20th century. Large numbers of African Americans moved north to work in the mills when the industry was booming. That hasn't been the case for decades, but the city still has a large African-American population.

Lew Wallace High is located in a residential area a few blocks off of Broadway, the main avenue through town. The surrounding houses are a mix of substantial older brick houses in good repair and smaller structures in varying conditions. It's not a slum. The shops on Broadway include nameless barbecue joints and check-cashing storefronts. Early in the morning, several still have accordion-style security barricades walling off their front windows and doors. In 1997 Gary topped Money magazine's list of America's most dangerous cities largely because its property crime rate was 43 percent higher than the national average.

Hanging on a wall in the main office at Lew Wallace is a portrait of the school's namesake, a Civil War general from Indiana who later wrote Ben-Hur. While a conglomeration of newer and older sections, some dating to the 1920s, the building features many of the same amenities as Carmel High: a well-equipped, brightly lit media center, large computer lab, a gymnasium, an auditorium, even a swimming pool. The school does have one thing Carmel doesn't: a pair of imposing metal detectors at the building's lone entrance.

Lew Wallace's enrollment is much smaller than Carmel, fewer than 1,200 students this year. The enrollment is almost entirely black but not entirely poor. Only about 35 percent of students qualify for free lunches.

As students arrive on a chilly Wednesday in January, Principal Clausell Harding and other staff are coordinating a field trip into Chicago for more than 100 students to see the play The Other Cinderella, an African-American take on the fairy tale. Later, in his office, Harding, who is in his seventh year as principal, explains that the trip is part of his administration's strategy of exposing students to experiences more typical of life in suburban households. The school also takes groups to visit college campuses.

Harding, who is black, like all but one of the senior administrators, says the school tries to be a place distinct from the rest of the inner city. When he arrived, the "gangsta rap" culture predominated. Rather than simply banning certain kinds of clothing, the school instituted a dress-up day once a month, when boys wear shirts and ties and girls wear dresses. If a student doesn't have such articles of clothing, the school supplies them.

"They used to wear the 'gangsta' clothes to get attention. All of a sudden they saw that they could get attention this way, and it's affected their grades and their general outlook on life," says the principal with pride. "They set their goals higher."

The steps being taken at Lew Wallace reflect many of the ideas of people like Payne and the Johns Hopkins sociologists. But they also point up the possible limits to how much a school can do. For all of the caring, encouragement, computers and "exposure," the performance of Lew Wallace students on the state graduation qualifying exam remains abysmal. In 1999, only 12 percent passed the math portion and 27 percent passed the language arts portion. Last fall those figures jumped remarkably to 26 and 43 percent, but they were still well below the state average and are about half of the rates at Indiana's best schools.

Lew Wallace is a long way from Carmel in another important cultural indicator too. While Carmel can't find room for all the parents who want to volunteer, at Lew Wallace only one or two show up regularly, says Doris Porter, the past PTA president who operates a Parent Resource Center open daily at the school.

Harding describes Lew Wallace's enrollment as one of the most economically diverse in the area. Some families live below the poverty line while others would be considered middle class. But with almost all of the students being black, the continuing low test scores only reinforce a troubling national phenomenon. Although the socioeconomic achievement gap cuts across races, even middle- and upper-class blacks continue to do worse on scholastic aptitude tests than socioeconomically similar whites.

In the 1998 book The Black-White Test Score Gap, editors Christopher Jencks of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and Meredith Phillips, an assistant professor of policy studies at UCLA, state that income accounts for only one point of the 17-point test-score gap seen between black and white 6-year-olds. The single largest difference they identify is middle-class parenting practices that they say are more typical of white families: reading to children, taking them on trips and using reason rather than flat edicts.

A boost in living standard doesn't instantly rewrite the hidden class rules that relate to school success. Warren Outlaw of the Educational Talent Search program, who remembers killing rats in the alleys with his friends when he was growing up, says all he ever heard when he was young was, "'Son, get an education.' It could have been from the wino or the gambler — anyone — because everybody said that."

But then as now, doing well in school wasn't cool in poor black neighborhoods, at least not among many adolescents. When he goes into high schools today searching for academic talent, he says, the black kids getting good grades are considered nerds.

"The term they use is, 'They're acting white.'"

He says part of the problem is that a substantial black middle class has existed for only a generation or two, so there aren't role models everywhere. When he was a kid, the saying was that the only black people who had made it were the teacher, the preacher and the funeral director. Even today, he says, when many African Americans meet a black person who is hospital's chief of surgery or in a similar prestigious position, "It's still a shock. The expectation is that these people shouldn't be in these jobs."

Outlaw isn't convinced that the socioeconomic achievement gap is permanent or inevitable. He says he knows of people from disastrous family situations who made it out of poverty through education, even if their own brothers and sisters didn't. If one child can get that old engine of social mobility to turn for him or her, he figures others can follow suit. He wants to know how to make it happen.

We all do, just as we all want to think schools can give everyone an equal opportunity for success. But it isn't that simple. Educational opportunities will never be perfectly equal. There will always be excellent and awful teachers, better-equipped and worse-equipped schools, the privilege of wealth to go outside the system and buy something better.

Yes, we should continue to lobby for better teacher salaries and school resources. But it's time we stopped looking at failing students and seeing only failing schools. It's time we recognized that parents are children's first and best teachers.

All is not perfect in the bakery, but it can turn out good pies. It's time we paid attention to the ingredients.

Ed Cohen was an associate editor of this magazine in 2001.