A field Mass at the doorway in May 1941. University of Notre Dame Archives

A field Mass at the doorway in May 1941. University of Notre Dame Archives

One century ago on Memorial Day — Friday, May 30, 1924 — the campus community gathered to dedicate a permanent landmark honoring former Notre Dame students who had died in or as a result of the Great War.

The armistice had been signed and the guns silenced more than five years earlier.

Today the east entrance of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart — the familiar phrase “God, Country, Notre Dame” carved into the stone above the oaken double doors — is known as the World War I Memorial Door. At the time, it was often called the “Soldiers Memorial Transept Porch” or simply the “Memorial Porch.”

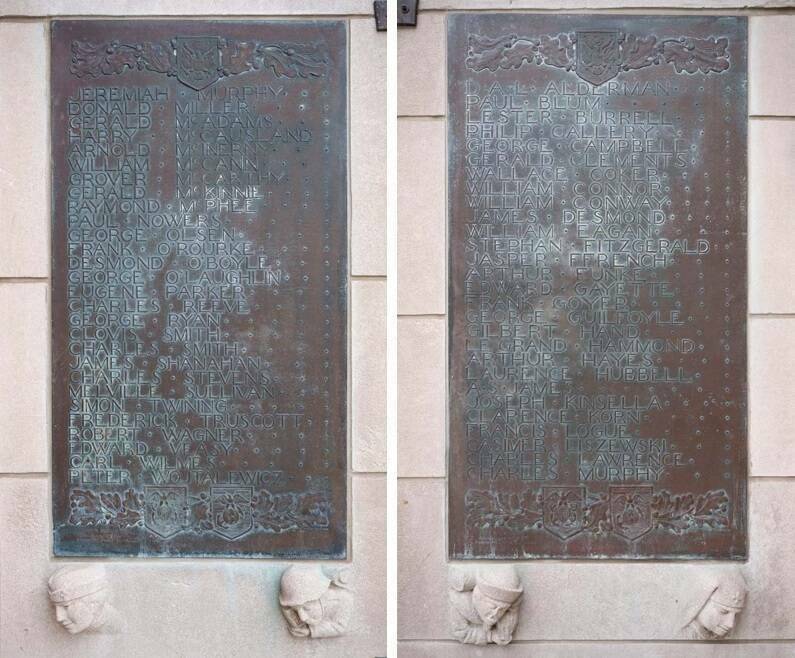

Shortly after the door’s construction, The Notre Dame Scholastic reported that some visitors were scratching the initials of former students who had died in the war into the yellow bricks on either side of the doorway. Two bronze plaques, bearing 56 names of servicemen listed as dead, were placed on the doorposts in late 1925. Those plates are now weatherworn, with a greenish white patina, but are still readable.

The list was compiled over several years based on notifications the University received of former Notre Dame men who had been killed in battle or died of other causes while serving in the military.

Of those 56 men, 13 were killed in action, two were declared missing in action and three died from noncombat accidents. The latter part of the war coincided with the global Spanish influenza pandemic, and at least 21 men listed had died of flu or pneumonia — often the last stage of the flu — in 1918 or 1919.

However, recent research indicates the century-old list of names isn’t entirely accurate or complete. Three surnames — those of Lester Burrill, William Egan, Class of 1917, and Michael Guyette — are misspelled. Nothing is known about five men who are listed with common surnames — James, Murphy, Olsen, Smith and Stevens. One former student who died in 1920 of a war-related illness isn’t listed. And five men whose names appear actually died many years later.

The new information is based on research conducted by John Hickey ’69 and Darrell Katovsich, a South Bend native who previously completed a comprehensive list and biographies of Notre Dame alumni who died during the Vietnam War.

Their research overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic. Hickey said he was surprised to learn how many of the World War I dead lost their lives to the Spanish flu.

He also was surprised to discover the names of men who lived for many years after the war. “I was gobsmacked. Record keeping around this was less than optimal,” says Hickey, whose grandfather’s South Bend construction firm was hired to build the memorial entrance.

Katovsich volunteered to help with the research. “I just thought it was the right thing to do,” he says. He doesn’t want men who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country to be forgotten.

After the United States entered the war in April 1917, some 350 members of that year’s graduating class enlisted. In total, about 2,500 Notre Dame men — students, faculty, alumni and priests — entered military service during World War I.

Private Frank J. Goyer, 19, believed to be the first Notre Dame man to have given his life in the war, died April 10, 1917. He had joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force, was mortally wounded at the Battle of Vimy Ridge and was buried in France. Born in Alpena, Michigan, he had attended Notre Dame from 1913 to 1915. He “was an exceptional student, possessing the qualities of a future scientist,” the Scholastic reported when announcing his death.

Captain George A. Campbell worked as a military instructor at Notre Dame from 1911 to 1917. He had served for more than 30 years in the U.S. Army in the Indian Wars, China, the Spanish-American War and elsewhere before volunteering again in Europe.

Campbell, 48, from Woburn, Massachusetts, was declared missing while under enemy fire on September 12, 1918, in Ardennes, France, and declared dead October 4. His body was never recovered.

“Captain Campbell was a fighting man who loved the smell of powder when war was going on and loved men and manhood in times of peace,” his Scholastic obituary stated. “He was a lovable individual that soon won a spot in the heart of every boy that attended the university or its preparatory school . . . and it was with a feeling of sorrow that he went away — but then there was fighting to be done.”

Campbell was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. In 1921, a newly formed Veterans of Foreign Wars post in South Bend was named in his honor.

Second Lieutenant Arnold “Big Mac” McInerny, 25, went missing in action while leading his command during an Allied advance south of Soissons, France. His date of death is listed as July 19, 1918. Buried in a makeshift battlefield grave, his body was never recovered.

McInerny grew up in South Bend, graduated from South Bend High School and entered law school at Notre Dame in 1914. He was a tackle on the Notre Dame football team in 1915 and 1916, and in the latter year was named right tackle on Chicago Tribune sportswriter Walter Eckersall’s All-Western team. “M’Inerny died a hero,” declared a South Bend Tribune headline above a story announcing his death.

Some of the dead were soldiers in training. Three were still attending the University and active in the Student Army Training Corps, a precursor to the ROTC. All three died of illness in October 1918, during the height of the influenza pandemic. The youngest was Private Lester Burrill, 18, who died in South Bend after contracting influenza and then pneumonia.

The name of Robert J. Thomas is not on the plaques. It’s likely no one at the University knew about his death. From Richmond, Indiana, Thomas attended Earlham College in 1916-17, then enrolled in the Army medical corps and served in France. He was wounded twice. After the war, he briefly attended Notre Dame in 1919 but died in July 1920 in a hospital in Evansville, Indiana, where he had been taken for a respiratory illness related to the gassing he suffered on a battlefield in France. It is possible that other Notre Dame men died as a result of the war without the news reaching the University.

How the names of men who were still alive at the time were included on the plaques remains a mystery.

“D.A.L. Alderman,” the first name listed, is Private Dallas G. “Dal” Alderman, of Goshen, Indiana, who attended Notre Dame in 1903-04. He served in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War I but lived a long life and earned a living in automobile equipment sales in Nebraska. He died at age 69 in an Omaha hospital in 1953, according to his obituary in the Burt County Plaindealer.

William F. Connor attended Notre Dame from 1914 to 1917 and served in the Army during the war. He retired as a civil engineer for the city of Decatur, Illinois, and died in 1982 in Pinellas, Florida, according to a newspaper obituary. He was 89.

At least nine of the men listed earned Notre Dame degrees. Another, Henry McCausland, was an engineering professor who graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and was considering entering the priesthood. The other veterans had attended Notre Dame as minims (grade school boys), prep students or college students who didn’t complete their degrees before entering military service.

Hickey and Katovsich provide a written account of their research and an index to their biographies of the World War I dead on the Notre Dame Class of 1969 Blog. The information is available at magazine.nd.edu/WWI.

Planning for a campus memorial had started soon after the armistice, an effort led by the newly formed campus VFW post and University administrators. The doorway was designed by Notre Dame architecture professors Francis Kervick and Vincent Fagan, Class of 1920. Funds were raised for the project through concerts, dances and alumni appeals.

The words “Our Fallen Dead” are carved into the stone at the top of the memorial’s facade. Statues of St. Joan of Arc and St. Michael the Archangel, added in 1944, stand in niches flanking the doorway. The phrase “In Glory Everlasting” is inscribed on the stone lintel over the doors. Above that, two carved eagles beside the University seal grasp a ribbon bearing the words, “God, Country, Notre Dame.”

At the Memorial Day ceremony, University President Rev. Matthew Walsh, CSC, Class of 1903 — who had served in Europe as one of at least eight Holy Cross priests who were military chaplains during the war — dedicated the entrance and celebrated a military Mass in front of it.

“The real purpose of a memorial, from the Catholic point of view, is to inspire a prayer for those we desire to remember. It is very proper that this memorial should be a part of the Church of Notre Dame,” Walsh said, the Notre Dame Daily reported.

“No one who knows Notre Dame need be told of the spirit of loyalty and faith that has animated this university from its beginning. We should imitate our dead in that they have shown us the lesson of patriotism,” he continued. “If only the people of America would follow their example there would be no discrimination because of race or creed. When Washington said that religion and morality are the basis of patriotism he gave us the definition to every patriotic move at Notre Dame.”

Walsh dedicated the door to veterans of World War I and the Civil War. “Let us ask God that this memorial will not only be beauty in stone, but also a reminder to pray for the men to whom it is dedicated,” he said.

For decades, an annual Memorial Day field Mass was celebrated at the doorway in memory of those who gave their lives in the Great War.

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine. Contact her at mfosmoe@nd.edu or @mfosmoe.