On the Monday morning before Thanksgiving in 1970, my father, Tony “Allatime” DePalma, pulled on his heavy, black-leather work boots, buttoned his insulated, plaid shirtjacket and walked the 7 1/2 blocks from our home straight up Third Street to the gated entrance of Pier C on the Hoboken, New Jersey, waterfront, just as he’d done nearly every working day for a quarter century.

They called him “Allatime” because it seemed he was always working, loading and unloading everything from bananas to bags of cement, from crates of fancy shoes to diesel locomotives so heavy they once snapped a steel cable that nearly tore off his leg. The waterfront was his life, as it was for thousands of broad-backed men like him in Hoboken and the other hardscrabble towns that lined the Hudson River back then. It wasn’t a glamorous job, and it didn’t pay well, but if you worked hard and kept your nose clean, the big ships and all they carried made it possible to support a family like ours.

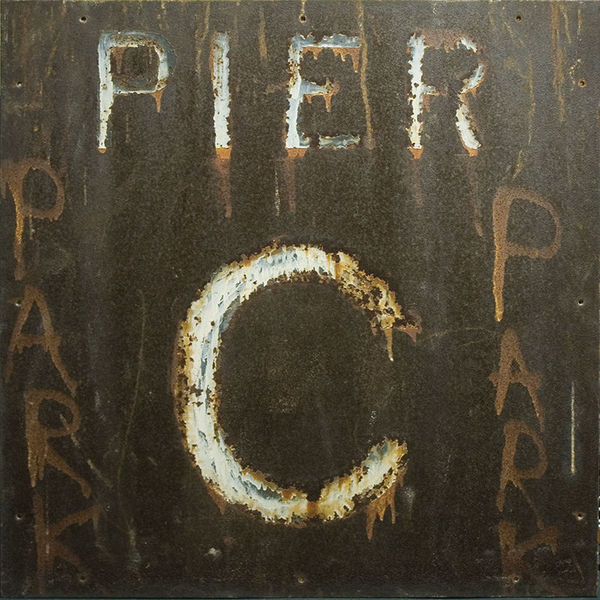

The humble routine of my father’s countless days on the docks suddenly veered into catastrophe for our family on that morning back when Nixon was in the White House and gasoline still cost 36 cents a gallon. Dad stopped at the gate separating the waterfront from the rest of the city and stood directly beneath the large, metal sign marking the entrance to Pier C. He couldn’t get in because a big padlock held the gate shut tight. We later found out that, sometime after he’d finished working the previous Friday night, the shipping company had abruptly pulled out of Hoboken and shifted operations to the piers at Red Hook in Brooklyn, where they had been offered a better deal. From that day on, no oceangoing vessel would ever anchor at Pier C or any other Hoboken pier. The hide-brown Hudson would continue lapping against the city’s ideally situated waterfront without a single longshoreman to hear it.

My father had been shocked to see that padlock, but he wasn’t surprised. All longshoremen had been expecting something like that to happen since they heard about the day in 1956 when the McLean Trucking Company lashed 58 truck trailers filled with goods onto the deck of an old cargo ship berthed at Port Newark. Six days later the Ideal X anchored at the Port of Houston, where the trailers were offloaded, hooked up to heavy trucks and driven away, without a single longshoreman laying his rough hands on the cargo. That experimental shipment would lead to the complete disruption not only of the shipping industry but of old ports like Hoboken — and the lives of old longshoremen like my dad.

The shipyard that once repaired giant ocean vessels is now cut up into expensive apartments, an upscale supermarket and the Hoboken Historical Museum, which has in its collection the Pier C sign my father passed under so many times.

The containerization revolution was just one of many such upheavals that have roiled our times. “The human race has seen more social and technological change in the past two decades than in all previous centuries combined,” Karthik Krishnan wrote last year. Krishnan is global CEO of the Britannica Group, a company that has the chops to talk about the challenge of pivoting with societal disruptions. Encyclopedias were still being sold door-to-door when Pier C was padlocked and I was a college sophomore, the first in my Italian-American family to go past high school. I saw what happened to my father that day and determined never to allow it to happen to me. Filled with self-confidence, I got my degree, entered the bright new media world, rose to the highest ranks in journalism and then, in the same way as my father, stood face to face with innovation that threatened to undermine my own career. Suddenly, Craigslist, Yahoo and Facebook were transforming the way journalism was paid for and delivered. They also were redefining news itself. Consumers could determine the shape and sound of their own news and get it on their cellphones, and in gas stations and supermarket checkouts — even in elevators and bathroom stalls — without any sort of quality control or truth test.

I never imagined it happening, but I had to accept the fact that newspapermen had become as dispensable as longshoremen.

Don’t get me wrong. I understand completely economist Joseph Schumpeter’s “gale of creative destruction,” and I appreciate the advantages of digital news delivery. I’m no Luddite about technology. I enjoy my Apple music, and I’m delighted that I can Facetime with my children and grandchildren wherever they may be. I thank God for the advances in health care that have drained the dread out of some cancers and given new life to those crippled by accidents and chronic diseases. But we now seem to be drunk on technology, with change coming so fast that it disrupts all levels of our society and culture. People, neighborhoods, whole communities, even entire societies end up suffering from the “future shock” that author Alvin Toffler predicted in 1970, the perception of going through “too much change in too short a time.”

While The New York Times and a few other large papers have adapted to the new media landscape, hundreds of smaller news organizations have succumbed to the internet onslaught, creating wastelands of misinformation that threaten the bonds of the communities they served for so long. In September 2018, Waynesville, Missouri, a town of about 5,000 residents along old Route 66, joined the more than 1,400 other American cities that, over the last 15 years, have watched their local newspapers die. The Waynesville Daily Guide suffered death by a thousand cuts, starting when the family that had owned the paper for decades sold it to a national media conglomerate, which then squeezed the life out of its pages. As the staff dwindled, the Daily Guide was published just three days a week, and who wants a daily newspaper that doesn’t come out daily? When the final issue rolled off the presses, the head of the local bank captured the impact of the paper’s death, telling the Associated Press that “losing a newspaper is like losing the heartbeat of a town.”

And when the Hoboken piers had shut down, it hadn’t been just our family that felt the loss.

“You gotta understand,” an old dock worker had told me when I reported on the demise of the Hoboken waterfront. “When a pier dies, a lot of people go under.”

Disruption has long accompanied progress. German steamship companies had attempted disruption of their own when they built the first piers on Hoboken’s waterfront in 1863, taking advantage of the city’s impressive position on the Hudson River directly west of midtown Manhattan and the lower cost of doing business near, but not in, New York City. The North German Lloyd line and other European shippers began bringing in goods and passengers to their fine, new finger docks stretching into the Hudson and did so well that by 1906 they were landing 652,000 passengers and 2.3 million tons of freight each year in Hoboken. So many of those passengers were German immigrants who decided to settle in the mile-square city that soon German was being taught in Hoboken’s public schools.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, soldiers marched up First Street and confiscated the piers and German ships docked there, including the 950-foot Vaterland, then the largest steamship in the world. When the Army was ready to send American doughboys to fight in Europe, Hoboken served as chief port of debarkation. More than a million young men shipped out under the command of Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing. Expecting a quick victory, they famously swore, “Heaven, Hell or Hoboken by Christmas!”

This history was familiar to all of us who grew up in Hoboken. And that past was part of our present. The federal government held onto the piers after the war ended, and in 1952 the U.S. Maritime Administration signed a 50-year, three-party lease with the city and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which then poured almost $20 million into a major overhaul of Piers A, B and C. It was around this time that director Elia Kazan brought a young Marlon Brando to Pier C to film On the Waterfront, a story about the violence and corruption plaguing New York Harbor.

My father was already working at Pier C by then, and he was offered a small part in the movie, but he turned it down. He didn’t need any Hollywood script to remind him of how bad things were on the waterfront. He’d known hiring bosses who needed a few bucks to help their eyesight when they were deciding who should work, and he’d lived through scenes like the one in Kazan’s movie where, in the demeaning ritual known as the “shape,” longshoremen desperate to be picked for work crowd around the boss so violently that he throws the work slips in the air, forcing the men to scramble like dogs fighting for a bone just to have a chance to do backbreaking work in the unforgiving cold for barely adequate wages.

In time, with a government commission keeping a closer eye on the docks, a lot of the corruption was eliminated, and the work was plentiful. Tony Allatime belonged to a regular gang of eight men, each with his own grappling hook and heavy boots. They’d empty out the insides of an entire ship, one sack, one box, one carton at a time. The method was called “break bulk” and sometimes the boxes did break, either accidentally or otherwise, and treasures spilled out deep down in the ship’s hold where it was hard to see who did what. Pilfering became so common that companies planned for it. One Italian shoe manufacturer tried to frustrate theft by shipping all of its left shoes in one load, the rights in another. The men worked hard for not a lot of money, and they considered whatever spilled from the broken boxes a rightful supplement to their meager salaries. They didn’t realize that they were quickening their own demise.

Twenty- or 40-foot-long steel containers don’t spill. They can be loaded at an offshore factory, hoisted onto a ship, taken down with a crane at a port and lashed to a truck that takes them to a warehouse without ever being opened. As the maiden voyage of the Ideal X proved so convincingly, containers could stop theft and slash labor costs. When On the Waterfront was being shot, my father was one of 30,000 longshoremen working the piers around New York Harbor. By the time Pier C was padlocked 16 years later, that number had already been drastically reduced, with no end to the bloodletting in sight.

In time, the truck-ready shipping container came to be known as the “longshoreman’s coffin.”

Besides his name, I inherited Tony Allatime’s willingness to work. Although I was still a student when Pier C was padlocked, I was eager to earn my own way. I had just turned 20 and had under my belt all of two Introduction to Journalism courses that I’d taken at Seton Hall, a diocesan university about 15 miles from Hoboken, when I wrote to the editor of our local newspaper pleading for work. The Jersey Journal was then a six-day-a-week afternoon broadsheet with a modest circulation. But it was our hometown paper, and more important, it was the only thing I ever saw my father read. I’d watched him many nights when he came home from the docks, took off those heavy boots that stained his white socks purple and, while my mother cooked, spread the Journal wide so it sprawled over half of the table. Wearing a pair of thick-framed eyeglasses, he’d read through the whole paper until it was time to eat, skimming most of the articles but never commenting on any of them.

In a place like Hoboken, at a time like that, it was more usual for the job to pick you than for you to pick your job. I was lucky. Tony Allatime never expected me or my three brothers to follow him to the water’s edge. We all went in different directions. One became a master electrician. One a Hoboken fireman. One worked in the office of a supermarket chain. I had my heart set on grappling with words and sentences, not bunches of bananas or sacks of coffee. I put the letter out of my mind until I came home one day to find a note from the editor offering me a chance to work at the Journal as a summer replacement. I started right after the Fourth of July and on my first day was assigned to cover the drowning of three Puerto Rican boys who had been playing pirate on a makeshift raft in the Hudson.

The Journal’s newsroom looked like a stage set for The Front Page, row after row of bulky metal desks each about the size of a Buick. I was assigned to one that was tucked into the back of the newsroom alongside a trio of noisy wire machines that always seemed to need reloading. I used a telephone handset that weighed as much as a dumbbell, connected to a switch box with ten toggles. I’d get there early enough in the mornings to see the old pressmen pushing wagons filled with lead type to be melted down to feed the Linotype machines that would turn my imperfect words into ink on paper that my own father would read. It was such a classic newsroom in those precomputer days that one of the nightside editors actually used a green eyeshade, one of the copy editors came in wearing a dapper three-piece suit and matching fedora, a copy of the Daily Racing Form tucked under his arm, and women were restricted to the women’s section, even farther back in the newsroom than my desk.

I worked general assignment that summer and the next, bearing witness to tectonic disturbances arising all around me. Hoboken already had shape-shifted from the city I had grown up in — a self-contained world of commerce, industry and tradition that, to my nerdy altar boy’s eyes, was near perfect. By the early 1970s it was tapped out, a forlorn urban strip where defunct businesses outnumbered operating ones, and suspicious tenement fires filled the nights with sirens.

Even Our Lady of Grace, the huge Catholic complex that stood around the corner from our house and had played such a prominent role in my life, was in sharp decline. The roof of the immense, brick church leaked, and the convent next door was almost empty. The Sisters of Charity no longer ruled the old four-story, block-long brick school building that had been erected in 1891 and then renovated in 1958 to accommodate me and the gaggle of baby boomers that filled the classrooms and most of the pews at the 9 a.m. Mass on Sundays. After eighth grade, we members of the Holy Ghost generation moved on to Catholic high schools all over Hudson County. Vatican II had just ended, and although I had no inkling of it, another great disturbance was underway. When I started at St. Joseph’s Boys High School, a few towns over, every class I took but one was taught by a La Salle Christian Brother. My Spanish teacher was the only exception, and he had trained as a brother before changing his mind.

But by my senior year, many of the brothers already had left, and St. Joe’s began a swift and painful decline that matched the fate of my elementary school, my church and my city. At Seton Hall, there were few black robes on the faculty. Nearly all my classes were taught by a quirky collection of lay professors. One afternoon one of them stunned me with an unexpected question. “Don’t you live in Hoboken?” she was curious to know. “We’re thinking of buying a house there.”

Really? This sophisticated philosophy professor and her brainy husband wanted to live in my exhausted hometown? The city that had lost its waterfront, where the church and school I had attended were crumbling, where my father’s 1960 Buick LeSabre had been stolen right in front of our house? I already knew that Hoboken’s fortunes had quickly gone from good to bad. What I heard from my professor was the first clue I had of how quickly a city could remake itself yet again, this time from bad to good.

I took more journalism courses and returned to The Jersey Journal for a second summer. Then one day, an academic adviser gave me some advice. “Newspapers are dying,” he told me. “The future is television.” At the end of my junior year I won a competition for an internship at a public television station working full time on a nightly news program that was broadcast from a converted bowling alley in Trenton.

TV news had its allure, but I longed for the written word. I freelanced for a number of magazines and started to write for The New York Times, getting assignments to cover, among other things, the Hoboken waterfront. Although the piers had closed, the longshoreman’s hiring hall that had replaced the “shape” remained open. My father had to report there every morning, and if there was work for him in Port Newark driving new cars off a huge ship from Japan, he’d have to take it. But if they didn’t need old-timers in Newark, all the men with seniority were guaranteed to be paid anyway, the result of a compromise between shippers and the longshoremen’s union that paved the way for containerization. He did that until he retired in 1976, but getting paid for work he didn’t do drained his spirit.

We pursued ways of life that we treasured, and that shaped and influenced the worlds we inhabited. And when both fell apart, it wasn’t just jobs and careers that were gored.The Hoboken hiring hall remained open until 1984, and on the day it closed I was there to report on the end of an era. You couldn’t say the place was filled with sadness or anxiety. It was more like resignation, an embrace of the inevitable by tough men used to doing a tough job. “Adios, Finidi,” one of them had written on the large blackboard where gang assignments were posted. “It’s all over.”

A few years later, after I was hired by the Times, I wrote an article comparing several generations of longshoremen in one family of working stevedores with my own family’s rejection of the docks. Budd Schulberg, who wrote On the Waterfront, came to our house to meet a couple of Hoboken longshoremen, including my dad, who for the first time opened up to me about working on the docks. “It was good,” he told me. “I had my time. But now it’s all gone.”

Indeed. There were only about 6,000 longshoremen left by then. But containerization had remade more than Hoboken’s workforce. Containerized shipping so dramatically lowered the cost of handling freight that it no longer was necessary, or even practical, for factories to be located near suppliers and markets. Freed from the exigencies of being close, it made economic sense for myriad consumer products to be fabricated halfway around the world and shipped to market. As containerization increased, New York’s manufacturing base collapsed.

Hoboken’s factories went belly up, too. After the piers shut down, Maxwell House’s giant coffee roasting plant was shuttered. Tootsie Roll, Levolor and countless other businesses left town. But the water’s edge was too valuable to let it sit idle for long, and the competition to redevelop the piers grew fierce. As Hoboken moved forward with plans to build on the docks, the old brick headhouse was torn down. It was on a day when a crane was ripping apart the imposing building that I interviewed Donald “Red” Barrett, who was there taking photographs. Red turned out to be a retired longshoreman from Hoboken who knew my dad. He also was an amateur photographer who had carried his camera with him while working. It was Red who told me that when a pier dies, a lot of people go under. It was also Red who let me glimpse a part of my father’s life that I had never really known. I’d always thought of working on the docks as rough, cold and disagreeably repetitive, and I never understood how my father, a man with a rugged, tattooed exterior but a gentle heart, could do it for so long.

But Red’s photographs revealed the intimate beauty of men working side by side, joined in a common task, usually without direct supervision and relying on each other to get the job done. Only with men you trusted could you steel up the courage to empty countless bags of cement from a ship the length of several football fields. When I asked my father about Red’s photographs, he explained that it was the camaraderie among the men that had made the work bearable, even enjoyable.

“They were good men,” he told me. Men who, like him, were known by names not given them at baptism but worn with a certain lopsided pride. Ask for Mikey Cabbage, Guinea Joe or Jimmy the Crabs and everybody knew who you were looking for. Tony Allatime taught me that work, whether done with your back or your brain, could be noble if it is done honestly and with integrity. This knowledge helped me as a journalist, enabling me to interview presidents and prime ministers one day, barbers and butchers the next, always with respect and a healthy dose of empathy.

At the Times I was able to move up to successively more challenging assignments, eventually being made a foreign correspondent. As I prepared to move to Mexico City with my wife, Miriam, and our three children, I met with the newspaper’s senior editors, including the legendary Washington bureau chief, R.W. “Johnny” Apple, an erudite bon vivant who knew as much about fine wine as he did about the finer points of national politics. I was impressed that he had a cappuccino machine in his office, the first one I had ever seen. Over a freshly brewed cup he let me in on a secret. “Being a foreign correspondent,” Apple grandly pronounced as he sipped his own coffee, its intoxicating aroma swirling around us, “is journalism as God meant it to be.”

It was a grand adventure all right. I arrived in Mexico with a cellphone the size of a brick and a few CDs with background articles from the Times and The Wall Street Journal for research. It was exciting to file articles to New York with my Radio Shack laptop, using a telephone coupler and an open line. Just as I settled in and Mexico entered NAFTA, the Zapatista rebellion exploded in the impoverished state of Chiapas. Mexico City was rocked by explosions and kidnappings. The presumptive next president was assassinated, and by the end of 1994 the Mexican peso was devalued, leading half the world into an economic tailspin.

None of that meant very much back in Hoboken. My dad never liked talking on the phone for long. When I called home, our conversation quickly came to the same question. “What kind of lousy job do you have?” he’d ask, perplexed by the need to be so far away for so long. “When are you coming home?”

The Zapatista uprising is considered the first internet rebellion. From their jungle hideout, the rebels used the internet to send out their own message, bypassing foreign correspondents. I had to listen to my editors in faraway New York tell me that they had read online things that were happening in Chiapas before I knew about them. By the time I returned to the U.S. in 1999, having spent a few years reporting on the other end of America in Canada, the web was changing the nature of journalistic work into something I hardly recognized.

I approved of the greater access that the internet provided, but I felt alienated by the often-silly ways that information was being turned into clickbait. Hundreds of American dailies were folding, and thousands of reporters and editors were losing their jobs. Not only was technology hastening news delivery, but Facebook’s goal of building “the perfect personalized newspaper for every person in the world” was flipping the very notion of what constituted news. “Even as news organizations were pruning reporters and editors,” the writer and historian Jill Lepore explained in her sobering assessment of journalism’s shaky future for The New Yorker, “Facebook was pruning its users’ news, with the commercially appealing but ethically indefensible idea that people should see only the news they want to see.”

I thought of that padlock on Pier C and realized it was time to make sure I did not end up on the wrong side of a closed gate.

By 2008, I was ready to take the buyout that the Times was offering employees. Before leaving the paper, I accepted a position with Seton Hall as writer-in-residence, teaching courses like News Literacy to help undergraduates navigate the new media landscape, while I continued to write articles and books. My education allowed me to take advantage of opportunities in a way not available to my father, who never went past sixth grade. And that, I now realize, was the key. Confronting future shock is a learned skill, and it may be a sign of these times that it now is being taught in various ways at universities across the country. For the past decade, for instance, all undergraduate business majors at Notre Dame have had to take the Foresight in Business and Society class, where they learn techniques for dealing with the future. Professor Sam Miller, director of undergraduate studies for the innovation and entrepreneurship minor at the Mendoza College of Business, says that trying to predict what’s coming is not effective because humans generally are “horrible” about predicting.

“But if you change prediction to anticipation, that changes the kind of questions you ask,” he says, and asking the right questions enables you to “pick up signals” that something new is in the air.

“The big future hack is not to have empathy necessarily with today’s world but to build empathy with future users, to understand a world through the eyes of that user,” Miller says. The point is to put yourself in the position of looking at future needs and priorities “in a way that is not overwhelmed by the gravitational pull of the status quo.”

Clearly, newspaper publishers and editors who ignored or misjudged the impact of social media kept thinking that the good times would never end, and they suffered because of that. During the decade after I filed my last article as a Times employee, newspapers shed nearly half of their remaining jobs, leaving just 38,000 people working in the most resilient papers. My old Jersey Journal has managed to survive, reduced from a proud broadsheet to a sickly tabloid. Even at newspapers that hang on, robots now do some of the reporter’s work and artificial intelligence undoubtedly will do more in the future.

If my father were alive, he would be genuinely shocked by Hoboken’s transformation from workingman’s town to high-priced Manhattan suburb. The old mill across the street from our house is now carved up into expensive condos, and just try to get into the no-name bar on the corner that is now a super-popular Mexican restaurant. The old Our Lady of Grace school building is now home to a nondenominational K-8 learning community that charges $23,900 for tuition. The shipyard that once repaired giant ocean vessels is now cut up into expensive apartments, an upscale supermarket and the Hoboken Historical Museum, which has in its collection the Pier C sign my father passed under so many times.

The relentless refashioning of our lives makes even sweeter whatever few strands of constancy we can hold onto. I still love going to the restaurant on Grand Street in Hoboken called Leo’s Grandevous that has Sinatra on the jukebox and the same tasty bar pies I remember as a kid. St. Joe’s is gone, but I remain close to Brother David, the vice principal, and see him regularly. And although my digital skills are quite good, I insist on reading dead-tree newspapers, sometimes spreading a broadsheet over the kitchen table, maybe just to prove a point.

But such points of fixity are becoming increasingly rare. We are now fully immersed in what one futurecaster has called “permanent volatility.” Uber undid taxi and limousine services, but how long will it be before self-driving cars undo Uber? My latest books are as challenging as ever to write, but the way they are printed, sold and read has been totally rearranged by Audible, Amazon and Kindle. In my short time teaching I quickly became aware of the major challenges facing higher education, and the potential of online courses to undermine brick and mortar campuses. And I’m not the only one. “Education from preschool to senior citizens is one of the greatest landscapes for disruptive innovation that we’ve ever seen,” Professor Miller told me, “but it still freaks me out.”

For Tony Allatime, being a longshoreman was a job; for me, journalism has been a profession. For him, cargo docks were work. For me, the printed word is a passion. Yet as different as our lives were, we both, Tony Allatime and me, “Allatime’s kid,” were so immersed in what we were doing that we sometimes lost sight of the rest of the world, leaving both of us vulnerable to those “gales of creative destruction” blowing around us. We pursued ways of life that we treasured, and that shaped and influenced the worlds we inhabited. And when both fell apart, it wasn’t just jobs and careers that were gored, it was the communities that the work had sustained, and the values that it had upheld, that were utterly transformed.

“What’s dangerous is not to evolve,” is what Jeff Bezos, the Amazon CEO, had emblazoned on the wall of the Washington Post newsroom when he purchased the newspaper for a song in 2013. It’s an attitude I’ve emphasized with my children, and I am committed to passing it on to their children, too. Whether for individual workers, or whole cities of them, it’s impossible to have on hand the resources to confront all possible futures. The only way to deal with creative destruction is to adapt to it, and the most important resources for doing so are resilience, flexibility and acceptance of the reality that change is inevitable.

As if to prove that point, I’ve just been invited to the 50th reunion of the departed St. Joseph’s Boys High School. It will be held in a fancy loft space that is one of the trendiest spots in the New York metro area. Located on River Street in Hoboken, it faces the corner that for over a century housed the famous Clam Broth House. It was from there that President Wilson addressed troops on their way to Europe during World War I. Where Sinatra performed and Brando became a regular while filming On the Waterfront.

And from the loft’s expansive windows I’ll be able to see three blocks away what used to be Pier C, where my father sweated and shivered and strained every muscle so many days and nights. It is now a leafy park on the water’s edge with a dazzling view of the New York skyline.

Anthony DePalma, a former visiting fellow at Notre Dame’s Kellogg Institute for International Studies, is the author of several books, including The Cubans: Ordinary Lives in Extraordinary Times, forthcoming from Viking in May. His son Aahren graduated from Notre Dame in 2004.