Photography by Matt Cashore ’94

Photography by Matt Cashore ’94

Daily health checks, mandatory face masks, grab-and-go meals eaten in tents on the quads, a maximum of two people on elevators, no in-person arts events or lectures, and a prohibition on unsafe student gatherings under penalty of dismissal.

After a summer of intense preparation, Notre Dame resumed in-person classes in August, but the campus environment was much different because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Eight days into the fall semester, and with the number of COVID-19 cases on campus already at 147 out of 927 tests (a positivity rate of nearly 16 percent), the University moved entirely to online undergraduate classes for two weeks in an effort to curb the outbreak.

University President Rev. John I. Jenkins, CSC, ’76, ’78M.A., said he was inclined at that point to shut down campus for the semester but changed his mind after further consultation with local health officials. “The virus is a formidable foe,” Jenkins said. “For the past week, it has been winning.”

Off-campus students were told to stay away. On-campus students were told not to leave. Visitors were barred from residence halls. The campus mask mandate was extended to require that masks be worn at all times, even outdoors, except while eating or in one’s own dorm room.

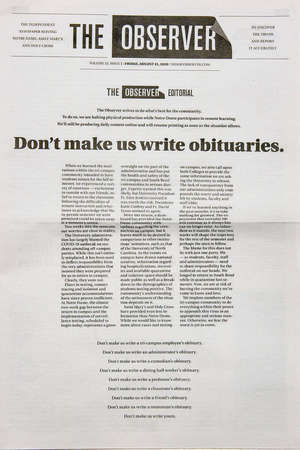

On August 21, The Observer, the student newspaper, published a front-page editorial headlined: “Don’t make us write obituaries.” The editorial took students to task for attending parties and ignoring mask-wearing and physical distancing and criticized administrators for flaws in testing, contract tracing and isolation accommodations.

Most of the early COVID-19 cases were traced to two off-campus student parties. By August 28, nearly 90 students were in process to face disciplinary hearings for violating health precautions.

The University’s approach soon showed promise. New case numbers dropped, and Notre Dame on September 2 began a gradual return to in-person classes. Many students breathed a sigh of relief, hopeful for the chance to stay through the fall semester.

A careful plan

Notre Dame had shut down campus and shifted to online classes in March as the coronavirus spread across the country. In May, plans were announced to resume in-person classes in August.

There is no playbook about how to reopen a university during a pandemic. From the start, officials said it would require careful attention, cooperation and teamwork by students and employees to succeed.

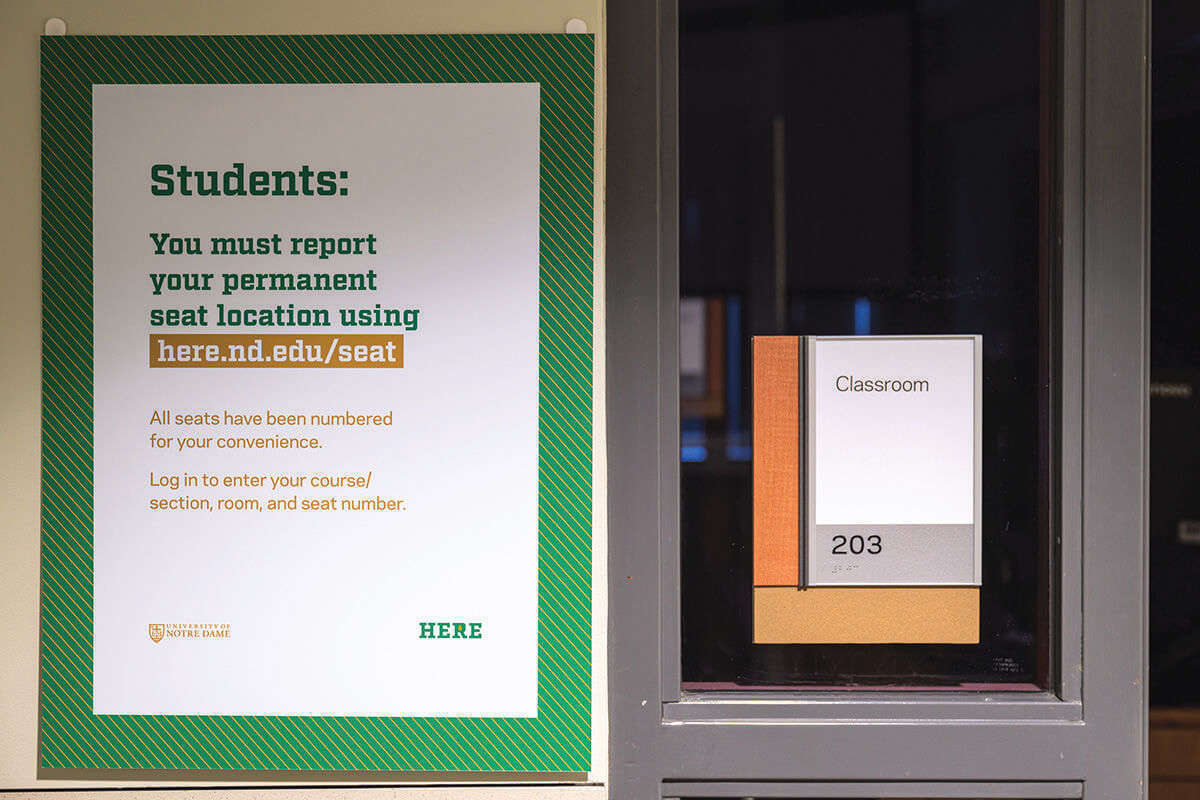

Over the summer, “HERE,” a University public relations campaign, distributed thousands of signs outdoors and in buildings across campus, reminding the community of safe practices in the age of COVID-19: “HERE we sanitize our hands.” “HERE we take the stairs when possible.” “HERE we practice physical distancing.” That sign was accompanied by an image of Touchdown Jesus demonstrating six feet of separation between his upraised hands.

More than half of the University’s employees continued to work remotely through the summer and fall. In July, the University withdrew as the host site for the September 29 U.S. presidential debate.

Meanwhile, the University set up a COVID-19 testing center at the southwest gate of Notre Dame Stadium. Leaders assured students and their parents a system would be in place from the start of the semester to test students and employees showing symptoms or exposed to the virus, as well as for contact tracing and quarantining. Rigorous safety measures were enacted to protect the health of students and employees.

The plan was designed to slow the spread of the coronavirus, which by September 15 had infected more than 29 million people and caused some 929,000 deaths worldwide.

The University required students to undergo testing before being approved to arrive on campus, partnering with a national laboratory to mail test kits to students’ homes. University Health Services received the results. A total of 11,836 prematriculation tests were conducted, identifying 33 positive cases — a rate of 0.28 percent. Students who tested positive weren’t permitted to return to campus until receiving medical clearance.

Once classes began, students and employees were required to complete a daily online health check, with only those who were symptom-free cleared to report for class or work.

Increasing cases

As the number of cases rose sharply in August, the virus taxed the University’s ability to meet the needs of those under its care. At first, some students reported delayed test results or being told they didn’t need testing, even if they had been in close contact with others who tested positive. Students in quarantine took to social media to complain about inadequate food deliveries and unanswered calls to the campus COVID hotline.

Junior Megan O’Gorman was among the first in quarantine. Suffering a sore throat and difficulty breathing, her results came back negative on a rapid antigen test, but she was told she would have to be isolated while awaiting results of the more accurate polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, test.

The University placed O’Gorman in an off-campus apartment. Her symptoms soon subsided. She said a contact tracer didn’t call until two days later, and she initially had to request food from Campus Dining because promised meal deliveries hadn’t arrived. She alerted administrators to these challenges “in the hope we could improve things,” she said.

O’Gorman never received her PCR test result, which she assumed was lost. On the eighth day, she again tested negative via the rapid test and was allowed to return to her residence hall.

The University reacted quickly to the criticism, hiring more contact tracers and addressing the glitches in food delivery. When South Bend residents reported some students leaving their quarantine units at off-campus apartment buildings and University-reserved hotel rooms, Notre Dame hired extra security guards to make sure students adhered to the policy requiring them to remain in their assigned rooms. Those who violated quarantine were told they would face sanctions, including possible dismissal.

Random surveillance testing of students and employees started August 21. University leaders closely studied the latest results, meeting daily to assess the numbers and to pivot the campus plan if necessary. The fate of the fall semester would not be an either-or decision, Provost Marie Lynn Miranda told students that day in a virtual address. A data scientist, Miranda specializes in environmental health research. The options were not simply “to keep everyone here or to send everyone home. There are a lot of places in between,” she said, such as the pause of in-person instruction that was three days underway at the time.

Through September 14, Notre Dame reported 660 positive COVID-19 cases — 615 undergraduates, 34 graduate students and 11 employees — out of 11,780 total tests since August 3, for an overall positivity rate of 5.6 percent. (Virus testing data is posted daily on the campus COVID-19 online dashboard.) The seven-day positivity rate through September 14 stood at 1.8 percent.

Notre Dame senior Justin Roy tested positive for the virus on August 17. In all, five of the 10 residents living in his off-campus house and a neighboring house tested positive.

Roy said he received his test results within 90 minutes, while he was still at the campus test site. He had no complaints about quarantine conditions. “We’re provided three meals a day and more water than we can drink. The COVID health care team calls every day to check on you,” he said from the off-campus apartment where he lived in isolation for 10 days.

He backed the University’s plan for an in-person fall semester, saying he was able to continue his classes online while in quarantine, but looked forward to returning to regular classes after the two-week hiatus. “If we can use this as a reset and get back to in-person classes, it would be beneficial to student life and to the University’s reputation,” he said.

Junior Jillian Randle lives in a house with seven other women students, all of whom contracted the virus. She tested positive August 17 and was placed in isolation. In quarantine, her symptoms — including extreme fatigue, chills, nausea and loss of smell and taste — worsened, and the University arranged a virtual appointment with a physician. “That helped me a lot,” she said. “I was hit harder by the virus than a lot of the people I know who had it.

“I feel very cared for here in isolation,” Randle said on August 24. She was released from quarantine four days later.

Over the summer, University employees had outfitted nontraditional spaces and auditoriums for classroom use to allow for physical distancing. Thousands of gallons of hand sanitizer were made available in every building, classroom and office.

Once students returned, staff teams frequently cleaned heavily trafficked areas, especially in residence halls and classrooms. Students were asked to join in the sanitizing effort. Professors were told to dismiss students by row at the end of each class in order to reduce congestion.

Trained employees, referred to as HERE ambassadors, were assigned to spots around campus to assist with the new protocols. Students were encouraged to practice the highest level of safety in all interactions, including at off-campus residences, restaurants and bars.

Renee Yaseen, a junior from Granger, Indiana, took a leave of absence this semester because of the virus. She knew she wouldn’t qualify for a medical-related waiver to take her classes online. But her father is a physician, and she didn’t want to put him and the rest of her family at added risk by catching the virus on campus.

“We’re a tight-knit family. If I were to be exposed, I wouldn’t be able to see them,” she said. “It was honestly one of the most difficult decisions I’ve made in my academic career. I miss my friends. I miss my classes. I miss campus life.”

Notre Dame’s enrollment in August was 8,857 full-time undergraduates and 3,619 full-time graduate and professional students, a 1 percent increase from the previous fall. Less than 1 percent of full-time undergrads took a leave of absence for the semester.

For new students, 2020 was an awkward introduction to college. Much of freshman orientation happened online via Zoom. Domerfest was canceled. Students were invited to Notre Dame Stadium one evening to watch Rudy on the large video board — each person in an assigned seat and sitting at least six feet away from

others.

Freshman Cece Swartz didn’t consider postponing her enrollment despite COVID-19. “If I didn’t go to college, what else was I going to do? It made sense to continue my education,” she said.

But college is different from what she anticipated. The face masks muffle conversation, making it hard to recognize people and make new friends. “I’m introverted by nature. Social distancing has made it harder,” Swartz said. Still, she hoped the temporary shift to online learning would work. “I’d be really disappointed to go home. I’m relieved we’re here and there is a chance we can stay.”

Planning for football

Notre Dame set strict meeting and event guidelines for the fall semester. The rules forbid nonessential campus gatherings: No tailgating or banquets. No public lectures. No artistic performances or films at DeBartolo Performing Arts Center. Those few visitors allowed on campus were required to abide by all safety protocols.

As of early September, plans remained in place for the football team to play a full season, which began in a surreal atmosphere with a 27-13 win over Duke on September 12. The scheduled game against Navy in Dublin was canceled. Other games fell from the schedule as the virus led the Big Ten and PAC-12 conferences to postpone their seasons.

Notre Dame, always an independent on the gridiron, agreed to play the 2020 season as a temporary member of the Atlantic Coast Conference. Ticket arrangements announced on August 31 limited attendance at home games to no more than 20 percent of stadium capacity, which meant only about 15,525 fans per game. Students received priority to buy season tickets, with the rest offered for sale on a single-game basis to faculty and staff. That left no tickets available for the alumni or the general public — a first — though season-ticket holders could reserve their usual seats for 2021.

The changes delivered a blow to the local economy. Irish home games in a typical year draw about 660,000 visitors, contributing an estimated $185 million to the region.

Players returned to campus in June and started formal workouts in July. To protect the team through the summer, the athletes lived in the Morris Inn, which was closed to outside guests.

Coaches, players and staff received regular COVID-19 testing. Between June 18 and September 11, 14 positives resulted from those tests (a positivity rate of less than 1 percent), requiring some players to be spend time in quarantine.

Faculty response

Many faculty members expressed strong opinions about Notre Dame’s reopening plan. Professors were told in-person teaching was the standard for fall, although individuals could request accommodations based on age, underlying health conditions or other factors, with medical documentation required. The requests were handled on a case-by-case basis by the Office of Institutional Equity.

Professor Tim O’Malley ’04, ’06MTS, is teaching a theology course this semester that meets in the spacious Leighton Concert Hall when in-person classes are in session. His 250 students sit in assigned seats spread out over the 840-seat venue in DPAC.

O’Malley wasn’t worried about in-person teaching. “Classrooms are the safest place on campus,” he said, noting masks are required, hand sanitizer is available and everyone stays at least six feet apart.

“Certainly many students are happy to be back. A lot of them are really committed to helping make this work,” he said. “If the University has to close down in-person classes [for the rest of the semester], there is going to be a lot of disappointment on the part of students and myself.”

Over the summer, at least 146 faculty members signed an online letter saying that they should be allowed to make their own decisions about whether to teach in person.

In a June 13 letter to the editor of The New York Times, Eileen Hunt Botting, a political science professor, urged Father Jenkins to reconsider his intention to reopen campus, arguing that it was a moral question and the lives of community members were at stake.

“What do we lose by working from home for one more semester? Nothing but some money. What do we gain by waiting to reopen until it’s safe? The moral certainty that we did the right thing for our community,” Botting wrote.

Sarah McKibben, an associate professor of Irish language and literature, was shocked by the decision to reopen campus in the fall. “There had been no survey of faculty or staff about reopening,” she said. Outspoken on social media in her criticism of the campus reopening plan, McKibben said the administration had acted responsibly in the spring by closing campus as the virus spread, but not so in the fall. “They made this decision without consulting with any of the faculty who would be spending so much time in close proximity to the students.”

Cooperation key

Relying on the most current medical advice about the coronavirus, administrators declared themselves optimistic that Notre Dame — with the cooperation of students and employees — could keep the campus environment healthy.

“The pivotal question for us individually and as a society is not whether we should take risks, but what risks are acceptable and why,” Jenkins wrote in a May 26 op-ed in the Times. “Disagreements among us on that question are deep and vigorous, but I’d hope for wide agreement that the education of young people — the future leaders of our society — is worth risking a good deal.”

Randle, the junior who spent time in quarantine, hoped the temporary shift to online learning would work and that campus life would continue for the rest of the semester. The late-August decision to pause in-person classes “was a wakeup call to a lot of people, both on campus and off-campus. We need to take this virus seriously,” she said.

She was looking forward to going back to the classroom. “I was proud to say I went to Notre Dame when they announced the reopening plan,” she said. “They are setting a great example for the rest of the world on how to live with this virus.”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.