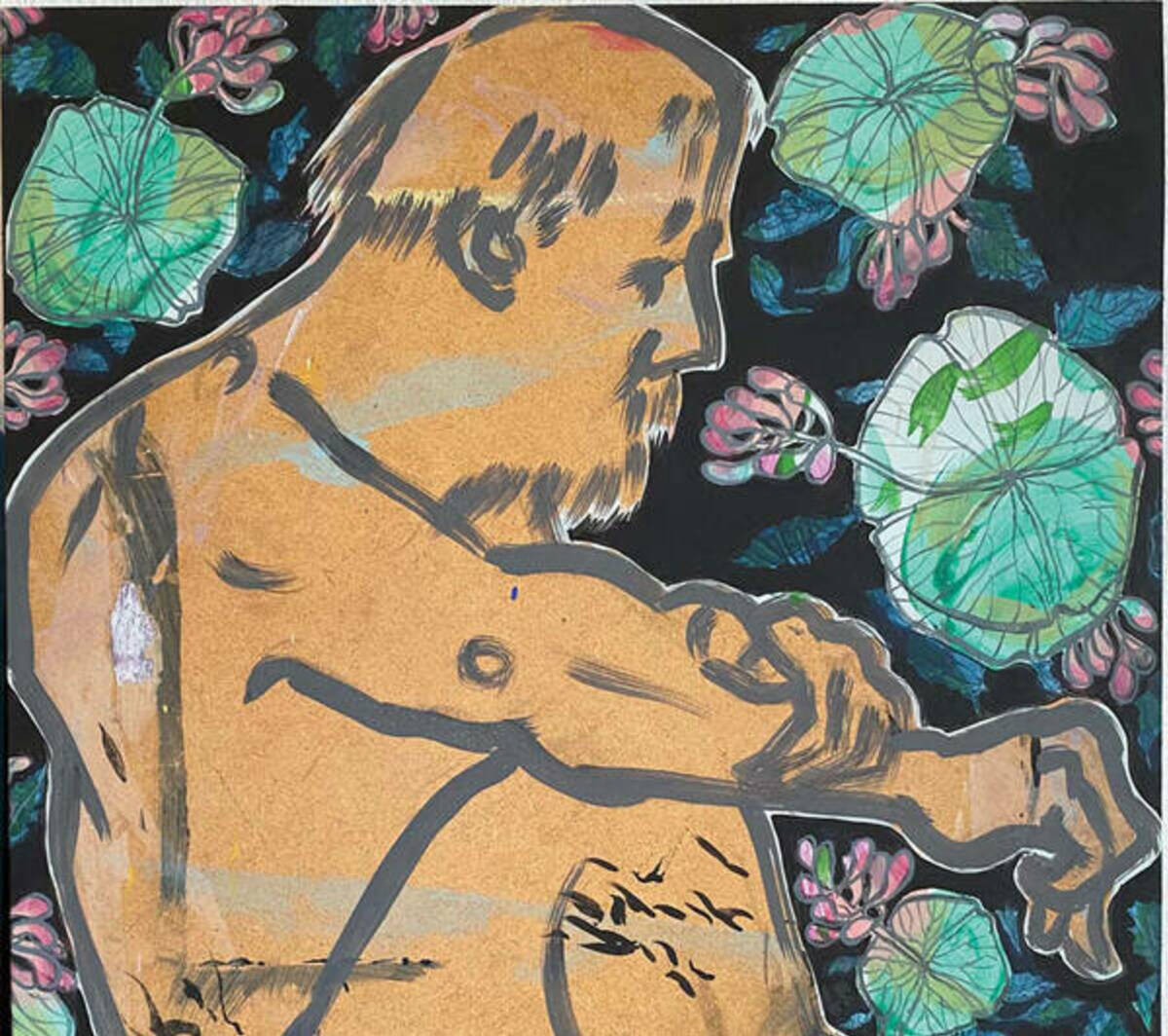

Illustrations by Birdie Thaler

Illustrations by Birdie Thaler

Although a year has passed since a woman has caressed me, longing isn’t why the sunshine of early spring feels to me like affection. Even when I was young and happily married and would stretch supine for long periods on my pond dock, careless about burn, surrounded by newly melted ice and tentative birdsong, I imagined that the sun caressed me. What has changed is that now I might notice how rapidly a sole cloud is sweeping the sky, and I will feel anxious and soon decide to go inside to check phone messages or clean the kitchen or perform some other task absent of seasons, and I stand and pull on my shirt, frightening and scattering bluegills that were sunning near the face of the water. Suddenly I am irritated, wondering why I am moving or what is moving me away from sunshine that I believed I could smell and taste and hold.

A conciliation of my wondering: Spring is here.

One morning when my wife and I rose from bed and saw the pond ice had melted, I said gloomily, despite the arrival of spring warmth, “Nothing stays solid forever.” I remember saying it because one of my uncles had died the previous day and because of Margaret’s happy reply: “Nothing is ever solid; is it?”

My winter life is much quieter than when she was alive. I seldom have anyone to talk to except my dog and myself. By choice, I have no television. Four decades ago, when Margaret and I moved into our home, it was not yet a modern house but a cramped cabin without utilities or even an electric generator. We heated with wood, illuminated with propane lights, carried our dishwater from the pond and our drinking and cooking water from a freshwater spring; and in the warm months, took baths together in the pond. Both before and after our home was connected to the grid and expanded, Margaret filled the empty spaces with her life. She was affectionate, fierce, talkative, lithe. She liked to sing along with the songs on our radio, though her singing was terrible; she also danced, and was beautiful at that.

The quiet lasts until the main bird migrations are underway. On a sunny afternoon each spring, I drive to a bog to set off in a canoe and hear the tumultuous red-winged blackbirds as they rise from and settle on tan spindles of cattails. Their screeching reminds me of Margaret’s singing, which I now miss. Their airborne undulations call to mind my maternal grandmother as she carried a red and black quilt outside in spring, and there, on the lawn between the white farmhouse and muddy pig pen, unfolded it and shook it free of coal dust, waving riddance to winter, urging the cold and short days farther into the distance. “Go outside all you can in spring,” she once advised me, “to thin your winter blood and get it flowing good again.”

In spring, bonding seems to be everywhere. In the air or on land or water, the bluebirds and robins and waterfowl couple; in sunshine, atop chilly soil, masses of garter snakes adjoin in wreathing, twisted balls of orgy. At night — in the pond and beyond in the creeks and ditches and patches of wetland and the vernal pools and the meadows and trees — so many frogs are pleading for mates that it is impossible for me to distinguish between the calls of the different amphibian species except for the toads, their cicada-like trilling rising in tone over the others. With the waters astir with life, the night air has a faintly swampy odor, and I like to suppose that toward dawn the singing will express satisfaction.

I was fishing one spring when I noticed a young beaver building a lodge. When it noticed me, it whacked its wide, flat tail on the pond and dove, making a half-somersault, and for a week, each time it spotted me, it disappeared beneath a thunderous explosion of water. Then it stopped paying me any attention at all until an afternoon when I was standing on the dock and it swam around and under me several times, head above water, submerged fur rippling, webbed back feet churning, tail a shifting rudder. In the shallows near shore, it followed me when I walked from the dock and along the bank. Margaret feared it had rabies, but I assumed it was lonely, curious or playful.

When the water had warmed and I began taking daily swims in late spring, the beaver left its lodge and traced me up and down the pond, occasionally diving when behind me and surfacing ahead — and since I swim naked, I was somewhat nervous each time it was passing beneath me. When I treaded water, so did it, nearly close enough for me to touch, and I could see its small eyes, dark and blinking, and hear its nasally breathing. Foolishly, I spoke to it in English; it knew a language no human can speak.

A day came when my friend was gone. Perhaps killed by a predator, or away seeking a mate. Consumed by or consumed with spring: In nature, is there much difference?

Last spring, I drove north to pick up a package of two dozen conifer and hardwood seedlings to plant on my property. I came to a small diner where Margaret and I occasionally ate when we were dating — or “sparking,” as her maternal grandfather had liked to put it. I drove by, changed my mind and turned around to order lunch. Nothing about the appearance of the diner had been altered: same wallpaper, flooring, tables. I kept looking toward the table where we usually sat. I could hardly believe the chairs were empty.

When we were young, Margaret and I planted bare-root seedlings on our 40 acres, a thousand or more each spring for six years. They are tall trees now. A neighbor who has a sawmill has logged some of the Norway spruce; some of the black locust I have felled, sawed into chunks, split and stacked to dry, and have burned in my woodstove. On a cold morning late last summer, I climbed a steep hill that overlooks my land and, from the crest, saw the thick, green, serrated crowns of my tree plantation and, beyond a range of hills in the distance, high over Cuba Lake, an enormous white plume. I tried to picture in the billow of diffusing, amorphous mist the departed souls of people I had loved. I couldn’t. The trees were enough.

Each spring has an ectopic day. The land is snow covered, and a portion of my pond has refrozen, and the tinny drumming and watery plunking in sap buckets has halted in the scattered sugar bushes until a warm, bright day comes round again. Or a freeze comes later when the wooded hills are already crimson, as if blood is pulsing beneath a lumpy, translucent skin, the reddish maple buds having swelled, and the sap buckets and sap lines and evaporator pans have been washed, dried and stored away until a new sugaring season. If snow falls even later, the hawthorn and wild apple trees and the oak, hickory and beech shed frosted, wilted blossoms; and for want of fruit and mast, wildlife will suffer more than usual the next winter.

Some readers believe T.S. Eliot was alluding to the fickle weather of spring when he wrote what has become probably his most familiar line: “April is the cruelest month.” Others believe the line is haunted by the tragically broken hope of his first marriage, the dead of World War I, or what Eliot saw as the spiritual and ethical enervation of Western civilization. I’m not sure what he meant precisely, assuming that five connected words can be amputated from a long poem and still have purpose, but the line does remind me of a certain E.B. White essay about nostalgia, hope and time.

In “Once More to the Lake,” White recalls a place where his father took him on a vacation, the memory having become halcyon. White takes his own young son to the lake, hoping the visit will be as wonderful as the one he likes to recall; but he writes, “I watched him, his hard little body, skinny and bare, saw him wince slightly as he pulled up around his vitals the small, soggy, icy garment. As he buckled the swollen belt, suddenly my groin felt the chill of death.” As if in a line of falling dominos, or passing years, White’s essay reminds me in turn of an Egon Schiele sentiment: “Within, and with your essence and heart, you feel an autumnal tree even in summer — it is this melancholy that I would like to paint.”

Late at night as the winter solstice approached in 2023, the year when my wife had died on the first day of spring, a phone rang. My electric blanket was turned up high. Snow swirled over my lawn and pond. Windowpanes chattered. I picked up the receiver of the cream-colored, rotary-dial phone that had been stored in a closet for well over a decade. On the line, the voice Margaret had when healthy and young. “Hello! Mark!” Then the line went dead, and I woke.

I shouldn’t make too much of my dream. If spirits exist they shouldn’t need to communicate through dreams or mediums, let alone telephones — though I was both sad and profoundly grateful to have heard distinctly, if only in a dream, Margaret’s voice vibrant. Flowing from a spring we once knew together.

A day will arrive when wood ducklings hatch in one of the cedar boxes elevated on posts over my pond. One after another they will heed the hen’s urging from below and bravely emerge from the nest, stubby-winged and fuzzy, to plop onto the water. About a dozen will swim after her within the V of her wake as she paddles to a far end of the pond. Usually they depart my property within a day or two, waddling over the pond bank — perhaps the hen feels threatened by my dog and me — and travel overland to a different pond even though the nearest is a quarter-mile distant and the forest and waters and sky around my home are populated with hungry predators, some with young to feed: raccoons, bears, weasels, minks, fishers, foxes, coyotes, bobcats, snakes, raptors, snapping turtles and largemouth bass, far more life and death than Dorothy feared in The Wizard of Oz, and all quite real. The hen might lead her clutch back to my pond several days later and again depart and return, each time with fewer young.

Annually, only one or two have ever survived until they could fly well. I hope this spring will be better. I make myself believe it: that a dozen will hatch and a dozen will fly into the liquid solidity of being.

Mark Phillips lives in southwestern New York and is a regular contributor to this magazine. His essays have been published or are forthcoming in The American Scholar, Commonweal, The Sun, The New York Times Magazine, Salon and other journals.