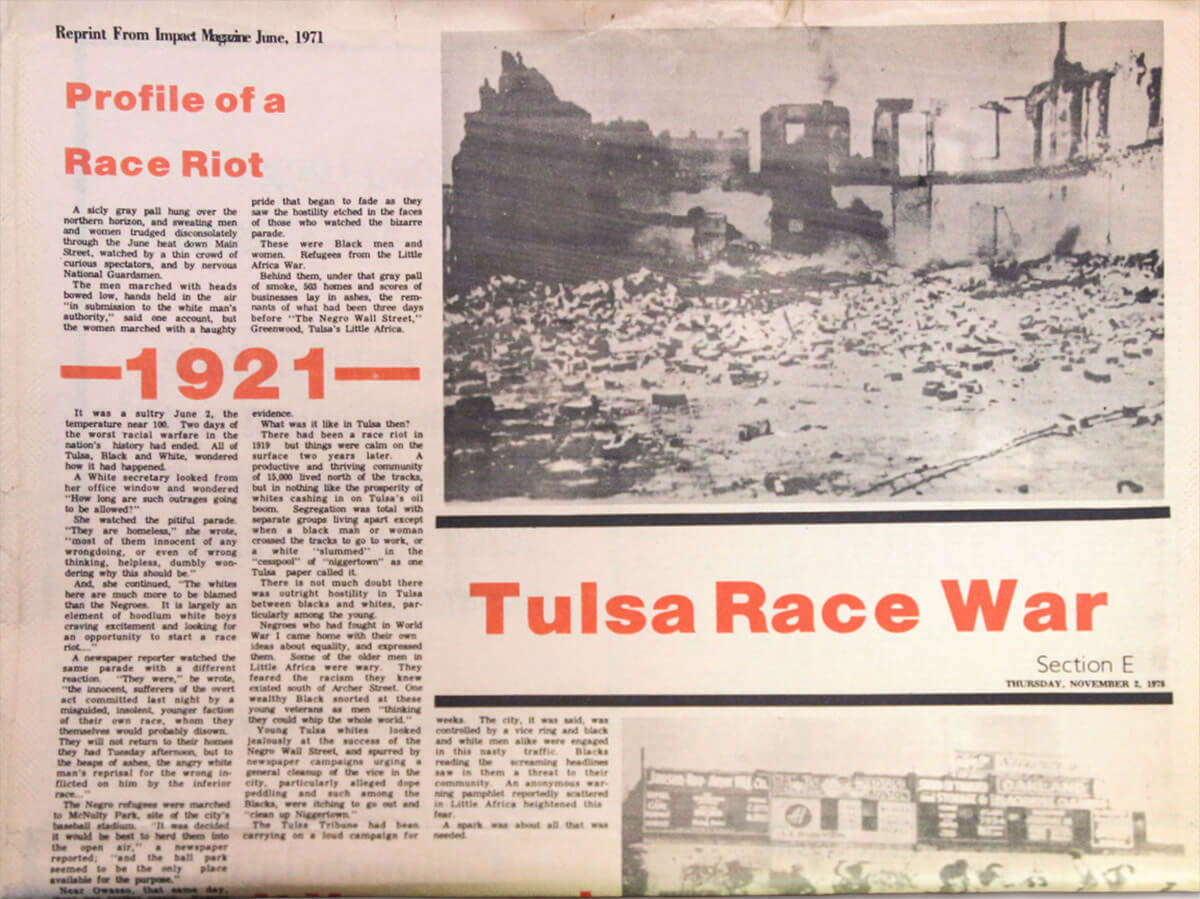

Gunfire blazed on the streets and sidewalks of the flourishing African American quarter of Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 1, 1921, as white mobs looted and burned homes, businesses and churches. The Oklahoma National Guard imposed martial law. Some Black residents were arrested, and thousands more were rounded up and interned in makeshift camps. By the time the violence ended, the city’s Greenwood District lay in ruins. More than 800 people were injured and as many as 300 people may have died.

The total number of people killed has never been determined because some victims were buried in unmarked mass graves while the bodies of others, according to eyewitnesses, were removed by train or thrown into the Arkansas River. The investigation of an all-white grand jury produced few charges and no convictions for the deaths, injuries or property damage.

Many Americans have never heard of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, one of the deadliest outbreaks of white violence against a Black community in American history, but for James O. Goodwin ’61, the events that took place in his hometown nearly 20 years before he was born shaped his life. Goodwin, 81, is a lifelong Tulsa resident, practicing attorney and longtime publisher of The Oklahoma Eagle, the city’s Black newspaper. His grandparents were Greenwood residents.

At the time of the massacre, the district was known as “Black Wall Street,” reputedly the wealthiest African American community in the United States. Many residents worked as domestics or laborers for white Tulsans who made their fortunes in Oklahoma’s oil boom. In those days of strict segregation, Black citizens spent their earnings in Greenwood’s thriving stores, restaurants, theaters and jazz joints, and they patronized Black physicians and attorneys.

The shooting began on Greenwood’s streets on the night of May 31, 1921, after a 19-year-old Black shoeshiner was accused of attempting to sexually assault a 17-year-old white female elevator operator the previous day. Rumors of a plan to lynch the Black teen spread after his arrest. By the time the violence subsided two days later, at least 35 square blocks of the Greenwood District and more than 1,200 homes had been destroyed.

The brutality and breadth of the massacre were soon all but lost to history. White residents didn’t speak of it. The city’s white-owned newspapers, the Tulsa Tribune — which had helped incite mob rage with its reporting on the teen’s arrest — and the Tulsa World, covered the violence, its aftermath and the grand jury investigation, then stopped mentioning it at all soon thereafter.

It was not until 1996, as the 75th anniversary approached, that the state legislature authorized a commission to investigate the events and prepare a historical account of what happened. Last year, Oklahoma’s Department of Education created a curriculum and required schools to teach students about the massacre. And this past October, 99 years after the brutal eruption, a forensic team unearthed 11 coffins in a section of the city’s Oaklawn Cemetery, where as many as 18 victims were reportedly buried together.

The deaths and destruction were never forgotten by The Oklahoma Eagle, the weekly newspaper that the Goodwin family has owned since 1936. The paper was founded in 1922, when a businessman salvaged a printing press from the burned-out building of The Tulsa Star, the city’s first Black-owned newspaper.

Over the decades, the Eagle has regularly published articles and interviews about the massacre and urged Tulsa residents to acknowledge the horror of that chapter of the city’s history. Goodwin and his newspaper have provided a relentless voice for the voiceless.

Long before desegregation efforts began in Tulsa and across the U.S., the Black news media and churches were the primary institutions providing cohesion, direction, education and a sense of belonging to African Americans. The Eagle covered the news of Tulsa’s Black community when other media outlets did not. Each week, its pages reported on African American businesses and schools, on births, deaths and meaningful life events, offering news of hopes, achievements and disappointments. The paper took strong editorial stands to promote racial equality and justice, amplifying concerns rarely aired in the city’s wider circles.

Goodwin was born in Tulsa in 1939, the fourth of eight siblings in a prosperous African American family. His father, Edward L. Goodwin Sr., was a businessman who in his 50s earned a law degree and became a practicing attorney, and who once said he purchased the Eagle because he was tired of being maligned by the “metropolitan press.” His mother, Jeanne, worked at the Eagle as an editor and proofreader and wrote a weekly column for nearly 60 years.

Like many of their neighbors, Goodwin’s grandparents had suffered property losses during the massacre, but were unable to collect insurance reimbursements because the companies said their policies excluded riot damage. Some Black families left Tulsa, but many stayed and rebuilt. White Tulsa continued to rely on Black domestic workers, waiters, porters, laborers, truck drivers and tradespeople. Goodwin remembers the bustling Greenwood District of his childhood in the 1940s and ’50s, when it was still regarded by many residents — white and Black — as “Little Africa” and known for its jazz musicians and clubs while remaining an enclave segregated from the larger community.

Starting at the age of 5 or 6, James Goodwin accompanied his father to the newspaper office on Saturday mornings. His chores included cleaning ink from the rolls on the presses and sweeping up metal scraps from the Linotype machine. It was tough, dirty work for the boy, but when he was finished, he was paid 30 cents, which he spent at movie matinees, taking in the latest serials and Westerns.

When Goodwin was 7, his family moved to a farm outside the city, where they raised cows, horses, chickens, goats and other animals. Two years later, he lost his right arm in a horseback riding accident that involved a train. He didn’t let it hold him back.

Goodwin left Tulsa in 1955 after convincing his parents he wasn’t getting a thorough education at his public high school. He hungered to study the great books, so he moved to Springfield, Illinois, where he lived with his grandmother and an aunt and finished his diploma at Cathedral Boys High School.

Although baptized Catholic as an infant, Goodwin attended mostly Baptist services during his youth. At Cathedral, he reconnected with his faith and started on his lifetime journey as a Catholic. On the advice of his aunt, he applied to Notre Dame and was accepted.

Notre Dame had graduated its first Black student in 1947. A decade later, Goodwin was one of still just a few African American undergraduates. Although this was before the height of the U.S. civil rights movement, Goodwin says he didn’t encounter racism on campus. “All of us felt privileged going there. None of us felt the stigma of racism in the sense that when we were in class we were treated any differently,” he says. Goodwin’s roommate was Percy Pierre ’61, ’63M.S., who later served as president of Prairie View A&M University and as a vice president at Michigan State. Another close college friend was Ron Gregory ’61, who went on to a career in social work.

Goodwin enrolled in what is now the Program of Liberal Studies, where he continued his reading in the great works of philosophy, literature, history, theology and the sciences that had long been his passion. During his senior year he received the highest grade in his class for a paper about James Joyce’s Ulysses. His 77-page senior thesis addressed racial disparities in employment in Tulsa. Pierre, who studied engineering, recalls how Goodwin would “come back from class and want to talk, so I listened. And then I started asking questions, and I started disagreeing with Jim’s interpretation of what he’d read. But I never read the books. He educated me on a lot of topics I needed to be educated on.” He was always “committed to what he’s doing and expects to succeed.”

Vivian Palm, a childhood friend, attended Saint Mary’s College while Goodwin was at Notre Dame. A romance ensued, and the couple married in 1961 while Goodwin was attending law school at the University of Tulsa. He has specialized in civil rights and social justice, winning Brown v. Oklahoma, a free-speech case that involved a local Black Panther, in the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972. He and Vivian, who died in 2012, had five children. Their daughter, Jeanne M. Goodwin, is the current editor of the Eagle.

James Goodwin has continued to lead the paper as publisher while maintaining his law practice, serving as its guiding light. “Jim is, first of all, a visionary. He has a picture in his mind’s eye of what might be,” says his youngest brother, Robert Goodwin, a former president and CEO of the Points of Light Foundation who received an honorary degree from Notre Dame in 2000. “The sign of any successful person starts with imagination. He sees a glimpse of what should be.” And he perseveres in his commitment to the Eagle’s mission. Its motto, “We Make America Better When We Aid Our People,” has appeared below the masthead since the 1930s.

The Oklahoma Eagle has covered cases of police brutality as far back as the 1930s. During World War II, the newspaper and the Tulsa branch of the NAACP joined forces to secure training programs and integrate the DuPont company’s Oklahoma Ordnance Works in Chouteau and Douglas Aircraft in Tulsa. In 1954, the Eagle surveyed Oklahoma’s top newspapers to gauge attitudes on the integration of the state’s public schools. In 1966, an editorial criticized Black residents for not voting in local elections. “A Voteless People,” it read, “is a Hopeless People!”

The paper reached its zenith in the 1970s, when its weekly circulation was about 20,000, including out-of-state mail subscriptions. It wasn’t uncommon for its news reports and editorials to be republished in other newspapers, including white-owned papers, as far away as Atlanta.

The Eagle has also launched the careers of some prominent African Americans. Carmen Fields worked there as a high school student and went on to become a Boston Globe editor, TV producer and host. Galen Gordon, a former intern, is now a senior vice president at ABC News. Thelma Thurston Gorham, former vice president and managing editor, later founded the Department of Journalism at Florida A&M. The philosopher, social critic and political activist Cornel West grew up in Tulsa and sold the paper as an Eagle newsboy. One-time editor and columnist Don Ross later worked at the Post-Tribune in Gary, Indiana — then served as an Oklahoma legislator for 20 years, sponsoring the bill that created the Tulsa massacre commission.

One of the 10 oldest Black newspapers in the U.S., the Eagle today operates in a one-story former automotive garage. Like many U.S. newspapers, it has faced tough times in recent years. Its news coverage is provided mostly by freelancers, and the paper twice has gone through bankruptcy reorganization. At any point, Goodwin could have decided it was time to sell or fold it. “But Jim would never consider that because of his commitment to our father and what he considered to be his legacy. And because of his understanding of the importance of the institution in terms of the life of the community,” Robert Goodwin says. Aside from three churches and a funeral home, the Eagle is the last original African American entity still operating in Greenwood.

“We’re coming up with different business strategies. There’s goodwill in the community that really wants to see the paper be sustained,” says David Goodwin, one of the publisher’s sons.

In recent years, Greenwood has experienced a revitalization, attracting trendy restaurants and eclectic music clubs. “We are facing the imminent prospects of gentrification and I’m trying to hold that back as best I can,” says Goodwin, who has a vision for educating visitors about the district’s African American culture and historic significance. A new museum, Greenwood Rising, is scheduled to open in 2021. “We only have a remnant of what it used to be, but I’m trying to preserve that remnant in a way that can make it a site for the entire city to enjoy. I want Greenwood to reflect its history,” he says.

Still, the Eagle remains vigilant on issues involving civil rights and the criminal justice system. In 2020, major stories included the ongoing search for the massacre’s mass graves, the lack of outreach to area residents about early voting options and the spread of COVID-19 in the Tulsa County Jail. One recent editorial took city leaders to task for removing a Black Lives Matter mural that was painted without formal permission on Greenwood Avenue.

The death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in May prompted protests and vigils in Tulsa as in other communities across the nation. When Floyd died, Goodwin says, Americans didn’t look at him as a Black man, but as a human being who happened to be Black. “It was pain that brought the world together,” he says. “You had this outpouring of pain that people felt in the humanity that they saw before their eyes.” The national outcry by people of all races renewed Goodwin’s sense of hope. Excessive police force and needless killing in the name of law and order must stop, he says.

The paper also covered President Donald Trump’s June 20 campaign rally in Tulsa amid the coronavirus pandemic, including protests and the subsequent news that Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt had tested positive for the virus after attending the rally without wearing a mask. “We are not blind, there were those who would have wanted chaos to be their response to Trump and his supporters,” the Eagle editorialized afterwards. “They were discouraged, thwarted, and their voices of violence drowned out by those who believe the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: ‘Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.’ This was a wonder to see.”

Goodwin says the paper will continue to fight for underdogs. “I was born into an environment that had a respect for American values. The story of America really is still unfolding. It has not yet gotten right with practicing what it preaches,” he says. “What it preaches is enduring to all of us here in America. We fight in order to live and die under the belief in the importance that all men are created equal and that liberty is a hallmark of our way of life.”

He adds, “In today’s America, many people think that Black folks or Hispanics or Indians are appendages, sort of extras to our society. And that’s just not looking at life as it is.”

Despite it all, Goodwin remains a man of firm hope and faith who is optimistic about the future, race relations and the quest for equality. Regardless of skin color, he says, many Americans share an appreciation for the value of liberty in American society and a fundamental belief in God.

“I regard myself as a prisoner of hope,” Goodwin says, employing a biblical phrase. “I regard myself as a person who came from prison. My forebears were prisoners of slavery and transitioned to prisoners of hope. . . . Our faith requires us to hope. I never, never lose hope, because to do so is to just surrender to the powers of men and not to the power of God.”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.