Felipe Esquivel Reed / CC BY-SA https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

Felipe Esquivel Reed / CC BY-SA https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

We all feel the new realities thrust suddenly upon us by coronavirus. Lenin’s famous statement comes to mind: “There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks when decades happen.” Still barely one quarter into 2020, everything feels different, as if an eon has passed but we don’t know what’s next. We grope for analogies, reference points, something to hang on to. Keeping our social distances, passing neighbors and strangers on the streets, we explore it all together, joking, Facetiming, Zooming, trading lists of films and TV series to watch, reading or rereading books we already own, finding ways to connect and think together. We are all in seminar.

Our seminar is global. The human species itself is working something out, thinking together. Not long after the virus was recognized for what it was, China notified the World Health Organization (December 31, 2019) and soon thereafter sequenced its genome, sharing the data worldwide. An immunologist at Scripps Research (California) began investigating its possible origins with other American scientists as well as a colleague from Sydney, Australia, and another from Scotland. They wanted to see if COVID-19 originated from a weapons lab somewhere or was “the product of natural evolution.” They concluded it was the latter, based on two unique features of the virus: its now familiar “spike protein and its distinct backbone.” A large number of labs all over the world, commercial, academic, governmental and international, currently work on possible treatment and prevention drugs and vaccines.

Public health statisticians from China, Italy, Spain — now from almost everywhere — exchange information, compare data, learn from (and teach) each other. “Flattening the curve” has become a familiar English-language phrase around the world as the global community looks at similar worst-case spiking graphs, compared to the more gradual curve that stretches out the pandemic’s peak, perhaps even diminishing the number of deaths, if the whole planet comes to understand what English speakers call “social distancing.”

In our collective efforts to find something familiar to grasp, some stabilizing reference point, Euro-Americans recall the so-called “Spanish flu,” though it is not so-named because that killer pandemic originated in the Iberian Peninsula. Rather, being neutral in World War I, Spain did not censor news of the disease already decimating armies of the warring countries, which kept it secret. Early reports therefore originated from neutral Madrid. Other historic events that changed everything in a short period of time come up: 9/11, Pearl Harbor, the Great Depression, even, in the U.S., the Civil War.

Others invoke literary work. Roger Cohen recently took time out from writing a novel to return to the opinion pages of the New York Times with a coronavirus column that invoked Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Albert Camus’ The Plague. Searching for ways to understand the enormity of 9/11, many writers recalled poet W.H. Auden’s “September 1, 1939,” a reference to Hitler’s invasion of Poland:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives.

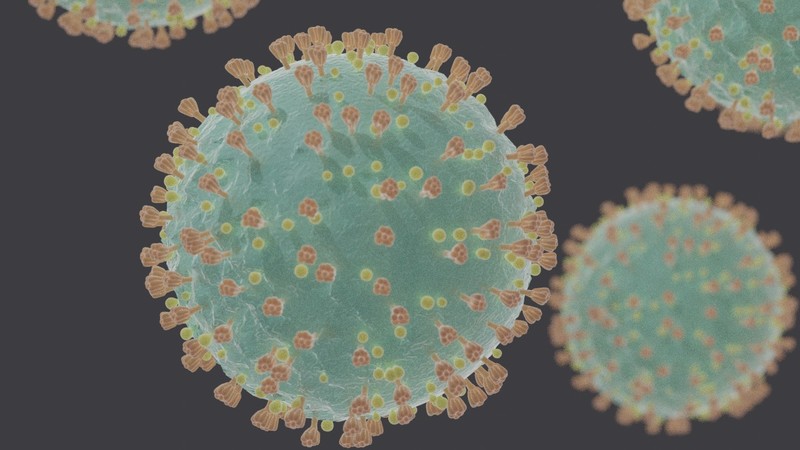

What’s obsessing my private life now, my reference point for solace in these increasingly unsettling times, is a visual one, based on a photograph — that now ubiquitous drawing of the coronavirus itself. A thousandth of the diameter of a human hair, spiky, sinister, looking like nothing so much as an underwater naval mine or a sharp-flanged medieval mace swung by a hairy, armored warrior in some fantasy comic book. It turns up everywhere: in newspapers, online platforms, cable and TV news programs, Steve Sack cartoons.

Like an earlier photograph, NASA’s famous Dec. 7, 1972 “Blue Marble” earth shot — but scaled in the opposite direction than the virus, our whole planet reduced to a dime-sized dot swimming in the vast blackness of space — that spiky virus globe provides profound perspective. It reminds me of ongoing evolution/creation. Like humans, like all forms of life, viruses too, even though not technically alive, collaborate with their host cells to adapt and change. Science, in the second half of the 20th century, significantly revised Darwinian theory with beginning understandings of bacterial evolution and more.

Darwin’s tree of life is much more complex than early schematics ever suggested, more like a web, as David Quammen calls it in The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life. A full 8 percent of the human genome, it turns out, is composed of viruses. Whatever life is, it stretches back much further than we once thought.

Someone asked me what I bow to when beginning my simple yogic exercises each morning, lessening the lower back pain from eight decades of walking upright on earth. “The Big Bang,” I answered, referring to the slang name for the event 13.7 billion years ago that seems to have begun our collective journey. Sometimes I’ve thought of that Blue Marble as I make my bow, but now I’ve added the spiked globe of the coronavirus to that awareness, along with the collective efforts of humanity to understand and mitigate its effect as it appears to have joined us in our journey, still outward bound.

Just as it took countless eons and tens of thousands of people to bring our planet to a moment when it could gaze at itself (that Blue Marble), so our collective work adapting to the coronavirus will involve millions of us, one way or another, to understand its workings, adapt and continue that outward-bound journey. I bow to that these days.

James McKenzie, a University of North Dakota professor emeritus of English, now lives and writes in St. Paul, Minnesota. His previous essays for Notre Dame Magazine include “The Redeeming Grace of Manual Labor.”