One day more than a century ago, an unsuspecting undergraduate student climbed the front steps of the Main Building only to be told that undergrads weren’t permitted on those stairs. And thus a Notre Dame tradition was born.

Students avoid those steps until their graduation day, generations of Domers have learned. The edict was strictly enforced by the Prefect of Discipline himself as far back as 1919, but before long students began enforcing it themselves, making it Notre Dame’s most enduring custom.

“I teach my classes in the Main Building, and if I go to walk down the main stairs, the students don’t. They’ll go around and meet me at the bottom. It’s a fun tradition,” says Brian Collier, a historian on the Alliance for Catholic Education faculty who teaches a course called God, Country, Notre Dame: A History of America.

Countless campus traditions have waxed, waned and transformed over time to meet the needs of a changing student body within a changing nation. What do these changes — and the firm traditions — say about the University and its culture?

Long traditions

“By the time students graduate from college, they accumulate plenty of courses but are not given enough credit for the traditions they bear,” writes the ethnologist Simon J. Bronner, author of Campus Traditions: Folklore from the Old-Time College to the Modern Mega-University. “Beneath the veil of play, student participants in campus traditions work through tough issues of their age and environment.”

Who doesn’t recall nervously waiting to meet one’s date to a hall dance? No longer held in the dorms, Notre Dame’s SYR dances, which go back to the late 1970s, remain touchstones of student life. (SYR originally stood for “Screw Your Roommate,” for the practice of roommates’ setting each other up with blind dates.)

Junior Parents Weekend, established in 1953, is still going strong, as are Bookstore Basketball (the world’s largest 5-on-5 outdoor basketball tournament, once perennially dominated by Father Monk Malloy’s powerhouse teams), the tasty grilled steak sandwiches served up by the campus Knights of Columbus on football game days, and the wacky Fisher Regatta, in which student teams race homemade boats across St. Mary’s Lake in hope of reaching shore before sinking.

Each graduating class still makes memorable first and last visits to the Grotto, and many students light candles for more special intentions than they can remember.

Campus faith traditions have changed over time, with daily Mass attendance in decline even before Vatican II and the student body becoming more religiously diverse. Still, every residence hall retains its chapel, with steady attendance at Masses on Sundays and at least one night each week. Many halls have developed their own food-related customs around these services, such as Dillon Hall’s popular Thursday night Milkshake Mass, after which the fellowship continues over homemade milkshakes.

Many students avoid stepping on the lawn on Main Quad — “God Quad” in current parlance. If you walk on the grass, legend has it, you’ll fail your freshman theology class. And if you kiss your significant other under the Lyons Hall arch, you’re fated to marry. Ditto if you hold hands and walk together counterclockwise around the campus lakes on a moonlit night.

Student high jinks

Some Notre Dame customs seem born from ordinary student high spirits and youthful ingenuity.

Case in point: Bikes in trees. Sometime a couple decades ago, an imaginative Domer picked up a bicycle that wasn’t chained to a bike rack and hung it from a tree branch. Somebody else copied the move, adorning another tree with another bike. It’s now commonplace during a stroll across campus to see a few bikes lodged in tree limbs. It’s not clear if this tradition originated at Notre Dame: Bikes in trees, we are told, are a thing at Purdue University and possibly other schools, too.

Look up in autumn, and you’ll see another mysterious custom. Somehow students manage to scale the “First Down” Moses statue next to the Hesburgh Library and impale a pumpkin on the figure’s upraised index finger.

In the past, students were subjected to “lake parties” for committing minor campus infractions — or sometimes just for having a birthday. This involved a dunking in one of the two campus lakes, a chilling prospect in the days before central heating. These “lakings” are no longer a regular thing, but the annual North vs. South quad snowball fight is another expression of cheerful student aggression that typically takes place on the evening of the first snowfall.

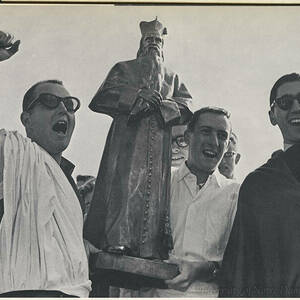

When it comes to student pranks, one can’t forget the legendary kidnappings (twice in the 1950s and again in 1962) of the Father Sorin statue from Sorin Hall. The good father returned each time, once via taxi cab and another time dangling from a helicopter. A similar heist circa 1984 swiped the Knute Rockne bust from the Rockne Memorial Gymnasium. After purportedly mailing photos and postcards from their travels, both artworks returned home. Bolted firmly in place, they haven’t strayed since, but passing students still rub Sorin’s foot and Rockne’s nose — and the bullfrog carving in Badin Hall — for luck.

Football traditions

Traditions related to football fandom remain some of Notre Dame’s oldest and most robust. The Drummers’ Circle, for instance, draws avid fans outside the Main Building at midnight before home games.

“Everyone shows up at Notre Dame at a different point in time. Those traditions are one way that you connect to that larger history,” says Katherine Walden, an assistant teaching professor of American studies who offers a Football in America course.

Students stand throughout football games in Notre Dame Stadium, as has been customary for generations. Many go clad in The Shirt, designed anew by students every year since 1990. They move their arms in unison as the band plays the 1812 Overture before the fourth quarter, a custom dating from the Lou Holtz era. And despite the best efforts of ushers and security, seniors have — since the late 1980s — smuggled marshmallows into the stadium for a massive marshmallow-throwing melee during halftime of the season’s last home game.

The Marching Band still performs its traditional outdoor concert before each home game — although the concerts moved from the front of the Main Building to the front of Bond Hall in 1997 to accommodate the growing number of band members.

Crowds continue to gather along Library Quad before the game to watch the Fighting Irish players walk to the stadium. The team used to walk from the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, but since 2011 has started at the Guglielmino Athletics Complex, with fans excitedly cheering and snapping photos along the route.

After each home game, the players gather near the student section, raise their golden helmets and join their peers in singing “Notre Dame, Our Mother.” Former head coach Charlie Weis ’78 started that tradition in 2006.

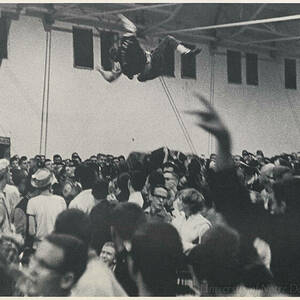

Pep rallies have changed with the times. For many years, they were raucous student-focused gatherings in the old Fieldhouse, then in Stepan Center, characterized by boisterous, stress-relieving shouts, shoving and human-pyramid building. Once they moved to the Joyce Center, they became tamer, more orchestrated affairs, aimed largely at parents and other visiting fans. Some pep rallies now occur outdoors on South Quad, and have a polished, made-for-TV feel.

Gridiron traditions help create a sense of identity and belonging for students and alumni, and serve as a means of building community, Walden says. “There’s a moment that being back on campus and seeing the sights and seeing the landscape takes you back to a place that, for many people, is surrounded in a lot of nostalgia and fond memories of a different period in your life.”

Fading away

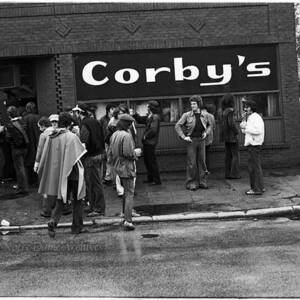

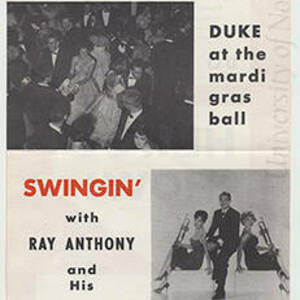

Some campus traditions have disappeared over time. Notre Dame hasn’t hosted a homecoming weekend since 1981. The annual campus Mardi Gras celebration and Alumni Hall’s Irish Wake have died. Other traditions have similarly gone by the wayside: the Senior Death March, in which seniors ceremoniously imbibed at a string of student bars on the Friday afternoon before the last home football game; the Beaux Arts Ball, a masquerade dance hosted by architecture students; and mock political conventions, earnestly conducted during every election year from 1940 until 1988.

“Quarter dogs,” the 25-cent hot dogs formerly sold late at night in The Huddle, eventually fell victim to inflation and, alas, are no more.

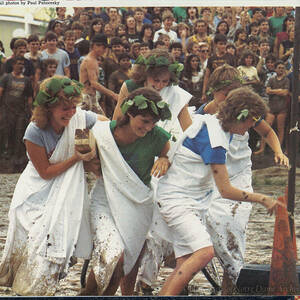

An Tóstal, the beloved, campuswide spring festival launched in 1968, and which included a kissing marathon, greased-pig chases, an interhall tug-of-war over a mud pit (Lyons Hall once hired an elephant as a ringer) and other forms of youthful mayhem, is now but a shadow of its former self. One recent iteration featured food giveaways, a Zumba class, mindfulness meditation and a zip line. “I’ve wondered why An Tóstal has faded,” Collier says, “because it was such a good thing. So many people met people outside their social circle and dorm for the first time because of the way it was set up.”

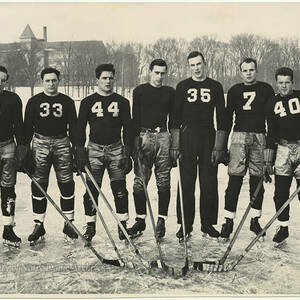

Pickup student hockey games on St. Mary’s Lake are largely a thing of the past. Many winters the lake doesn’t freeze solid enough to allow for skating. Students do still occasionally “borrow” trays from the dining halls to go sledding on Holy Cross Hill.

The Sophomore Literary Festival, a major annual event founded in 1967, drew such luminaries as Norman Mailer, Arthur Miller, Margaret Atwood and Allen Ginsberg. In time, renamed the Notre Dame Literary Festival, it struggled to attract the celebrity authors and large crowds it once commanded before it vanished altogether about five years ago.

Class rings are no longer a must-purchase item as they were for previous generations. “I think jewelry in general with this generation is less of a thing. And because of social media, people already know where you went to college,” Collier says.

The Freshman Class Directory is no more. Decades of students flipped through the pages to choose SYR dates, but Facebook, Instagram and other social media rendered it obsolete. The last of these infamous “Dog Books” was printed in 2018.

Some behavior shifts, not always positive, came just before or shortly after the admission of undergraduate women. A few customs seen as sexist or vulgar through contemporary eyes have met their end. They include panty raids of Saint Mary’s College, conducted by Notre Dame men from the 1960s into the ’90s, and the erstwhile “Ugly Man on Campus” contest.

During the 1970s, students on North Quad occasionally dispatched a naked runner to the distant Rockne Memorial on a frigid winter night to pilfer a student-issue towel as proof and trophy. That tradition morphed into the all-male Bun Run through the Hesburgh Library and, in later years, LaFortune Student Center. That tradition was snuffed around 2015, after The Observer published a letter to the editor from a food-services manager who described how upsetting the custom was to employees on duty during the nude horde’s stampede.

While some campuswide traditions have collapsed as campus has grown, focus has shifted to the residence halls. The Keenan Revue, the annual humor show organized by that men’s dorm since 1976, has flourished in this new milieu, as have LHOP, the Lewis House of Pancakes, a late-night breakfast served to visitors who walk from section to section; Alumni Hall’s Friday afternoon outdoor dance party;

Keough’s annual chariot races and kangaroo zoo; and Siegfried’s Day of Man, when residents venture out into the February cold in T-shirts, shorts and flip-flops to raise money for a homeless shelter.

On the other hand, some newer, student-generated traditions, such as Disorientation (“Dis-O”) and PigTostal, have found their footing, along with certain Senior Week activities. Some of these are not officially sanctioned by the administration, nor are they to be encouraged by staff, as they mix typical college rowdiness with peer pressure and liberal alcohol consumption.

A few reboots

Some customs have grown, changed or reinvented themselves.

For years, watching Knute Rockne, All American in the Knights of Columbus hall was a rite of passage. “Don’t get on the plane, Rock!” students would call out at that fateful moment during the film. These days, students gather in the stadium before classes begin each August to watch Rudy, the 1993 film about the famous Fighting Irish walk-on.

Collier attends every year. Today’s students mostly socialize during the film, he says, except for one scene they find riveting. It’s the fourth time Rudy applies to Notre Dame, “and he gets his acceptance letter, and the students go nuts. It’s the only thing in that movie they can all relate to, because they all waited for an acceptance letter from Notre Dame,” he says. “I’m touched by it every time. That piece carries across the generations.”

Collier has crafted his own “Senior Bucket List” — 50 Notre Dame experiences he recommends before graduating. The suggestions include an outing with each roommate you’ve had during college, visiting every residence hall and going on an old-fashioned date.

The Bengal Bouts boxing tournament, a tradition for Notre Dame men since at least 1931, remains popular and continues to raise money for Holy Cross ministries in Bangladesh. In 1997, the women’s boxing club debuted the Baraka Bouts as a fundraiser for the congregation’s work in East Africa.

The custom of Notre Dame bachelor dons — unmarried male professors who lived in residence-hall apartments — came to an end in 1980 with the death of Paul Fenlon, the Class of 1919 alumnus who had lived in Sorin Hall for more than 60 years. In recent years, that idea got a fresh spin with the faculty-in-residence program, which introduced married professors and their spouses into a handful of dorms.

While the prohibition on walking the front steps of the Main Building remains solid, students have augmented their celebratory commencement-weekend climb by sharing champagne and cigars.

Alumni traditions

In recent years, some alumni have started leaving small offerings — perhaps a six-pack or a gift card for a coffee shop — outside their old dorm rooms as gifts for the current residents.

Of course, it’s common for alumni returning to campus to visit the Linebacker Lounge and try out their rusty moves on the crowded dance floor. While other student bars have come and gone, the ’Backer — founded in 1962 — lives on.

Since the 2015 death of longtime University President Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, some alumni (and students, too) make a pilgrimage to his gravesite in the Holy Cross Community Cemetery to smoke a cigar in his honor. (Hesburgh enjoyed a good stogie.) Visitors also sometimes leave prayer cards, rosaries or other mementos on the gravestone.

“All traditions serve a purpose, and they have to be able to organically grow or fade,” Collier says. He sometimes is troubled by efforts to market longstanding campus customs, like the pep rallies, rather than allowing them to blossom or die naturally. Students are drawn to the authentic, he says, which brings us to his challenge to the next generation of students: “What traditions will you bring to Notre Dame? What customs can you start?”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.