“GameDay" and other bright media spotlights have altered the landscape of college sports. Matt Cashore ’94

“GameDay" and other bright media spotlights have altered the landscape of college sports. Matt Cashore ’94

When I played football at Notre Dame in the 1960s, the NCAA allowed teams to make only one national television appearance during the season. For instance, in 1966, the late-season Notre Dame-Michigan State game, often referred to as the “Game of the Century,” was televised only regionally because Notre Dame had used its one national TV slot against Purdue.

Both No. 1-ranked Notre Dame and No. 2 Michigan State were undefeated. A controversy continues to this day over Notre Dame’s decision to run out the clock rather than risk a turnover in the final moments of the game. The final score was 10-10. The following week Notre Dame crushed 10th-ranked Southern Cal 51-0 and the players learned on the flight back to South Bend that the Associated Press and other polls had named our team the national champion.

In that era, the champion was named before the college football bowl games. Because of this, and Notre Dame’s policy of not playing in bowl games, team members were able to concentrate on school work and prepare for final exams.

College football in my era had its share of corruption, but NCAA policies were in place that made it very clear that being a student was a priority. There was no freshman eligibility, we practiced 20 hours a week during our 10-game season and, after spring practice, there was no reason to make contact with a coach until preseason practice in late August. Most players worked out on their own during the summer.

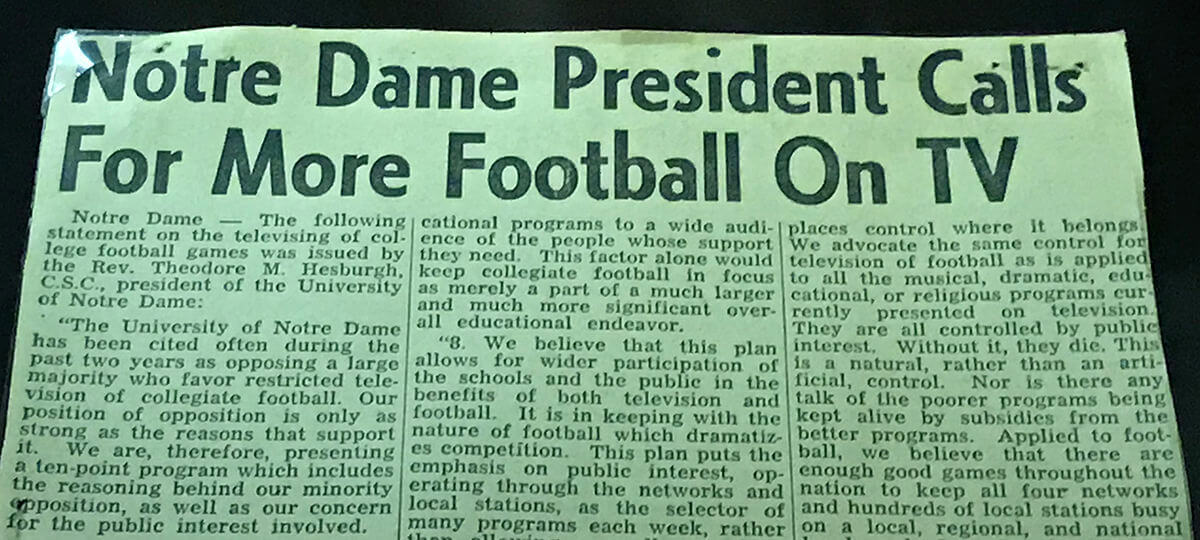

When I played in college, I never focused on which of our games would be televised. Notre Dame president Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, however, passionately believed that each school, and not the NCAA, should be in control of how many of its games could be televised. In 1976, 61 football powers formed the College Football Association (CFA) to lobby the NCAA to give them a bigger share of television revenue. The NCAA gave in a little, but Father Hesburgh still viewed the NCAA’s total control of the sale of television rights as “socialism.”

“Enough good games” for all the networks, Hesburgh said in 1953, via the Special Collections exhibit, Touchdowns & Technology.

“Enough good games” for all the networks, Hesburgh said in 1953, via the Special Collections exhibit, Touchdowns & Technology.

In 1982, the universities of Georgia and Oklahoma, with the support of the CFA, decided to sue the NCAA on antitrust grounds. A federal district court ruled in favor of Georgia and Oklahoma, calling the NCAA a classic cartel. The case, often referred to as the Regent’s Case, went to the Supreme Court in 1984. The court accepted the argument that colleges and universities, like any other business, should be able to sell their football television rights to the highest bidder.

The most poignant statement I have ever read regarding the 1984 Supreme Court ruling was written by Justice Byron White, the author of the dissenting opinion. White, an All-American football player at the University of Colorado in 1937, wrote that his fellow justices “err in treating intercollegiate athletics under the NCAA’s control as a purely commercial venture in which colleges and universities participate solely, or even primarily, in the pursuit of profits.” Justice White was right on target.

Competition for television money in the 21st century has put tremendous pressure on coaches to win, which in turn puts greater pressure on them to recruit “blue chip” players, including those whose academic credentials fall well below those of the rest of the student body. By ruling that big-time college sport is a business like any other, the Supreme Court seriously undermined the educational integrity of some of the countries’ most academically respected colleges and universities.

The University of North Carolina, for instance, was found guilty of admitting athletes who could barely read and write, and directing them into independent study classes that required little or no work. This kind of academic corruption is a logical outgrowth of the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Regent’s Case that college sport is just another business, and many schools will do just about anything for a bigger cut of college football’s “pot of gold.”

Not only did universities lower academic standards, they also subjected athletes to a regimen of workouts and team meetings that would make it hard for anyone to excel in the classroom. Of the 409 athletes in the Pac-12 conference interviewed by a strategic marketing firm in 2016, 71 percent reported sleep deprivation as the major barrier to their academic performance. An NCAA study in 2016 found that Division I football players spend 43.3 hours per week in athletic-related activities.

The Supreme Court ruling encouraged other practices that are perfectly acceptable from a business perspective, but make it difficult for sleep-deprived athletes to excel in the classroom. For instance, football season in the NCAA’s top division now ranges from 12 to 15 weeks depending on participation in playoffs. Midweek games are scheduled with no concern for academic demands, rest or recovery.

The Supreme Court’s 1984 ruling was also a financial windfall for college coaches. Clemson’s Dabo Swinney, for instance, is making over $9 million in 2019, not including bonuses and outside income, and Alabama’s Nick Saban isn’t far behind. College football coaches are among the highest paid public employees in most states, often making far in excess of the college presidents or chancellors who lead their “not for profit” institutions.

Since 1984, college sport, especially big-time college football and basketball, has been transformed into a multibillion-dollar industry that swamps educational values and exploits the cheap labor of the players. Nonetheless, there is still a way to restore a modicum of academic integrity in big-time college sports. Serious reform would require Congress to grant the NCAA a limited antitrust exemption.

An antitrust exemption could include requirements such as shortening football seasons, capping coaches’ salaries, instituting strict time limits on sports requirements for athletes and imposing educational conditions on member institutions. Without an exemption, the NCAA could be exposed to substantial antitrust liability from such actions.

Although a limited antitrust exemption could substantially enhance educational opportunities for college athletes, it would not address the fact that big-time college athletes do not receive fair financial compensation for the millions of dollars they generate. Under pressure from growing numbers of sports fans, as well as members of Congress, the NCAA has recently proposed that players receive financial compensation.

The crux of the proposal, with details still to be worked out, is that college athletes would be permitted to obtain employment and accept remuneration for the commercial use of their own names, images, and likenesses (NILs) for advertisements, public appearances, speaking engagements and product endorsements. Athletes could model athletics apparel or be paid sport instructors or camp counselors. The list could go on.

Thirty-five years ago, the Supreme Court seriously undermined academic integrity in college sport by treating it like any other business. The ruling trashed academic values (compromising the one part of the arrangement for which athletes were compensated through scholarships) and transformed them into otherwise unpaid employees in a multibillion-dollar industry. Slowly but surely, activist groups, including both men and women, have fought to restore academic integrity and fair financial compensation for the athletes.

The battle is still raging, but the tide may have turned.

Allen Sack, a professor emeritus at the University of New Haven, played on Notre Dame’s 1966 national championship football team. He is a co-founder of the Drake Group, whose mission is to defend academic integrity from the corrosive aspects of big-time college sports.