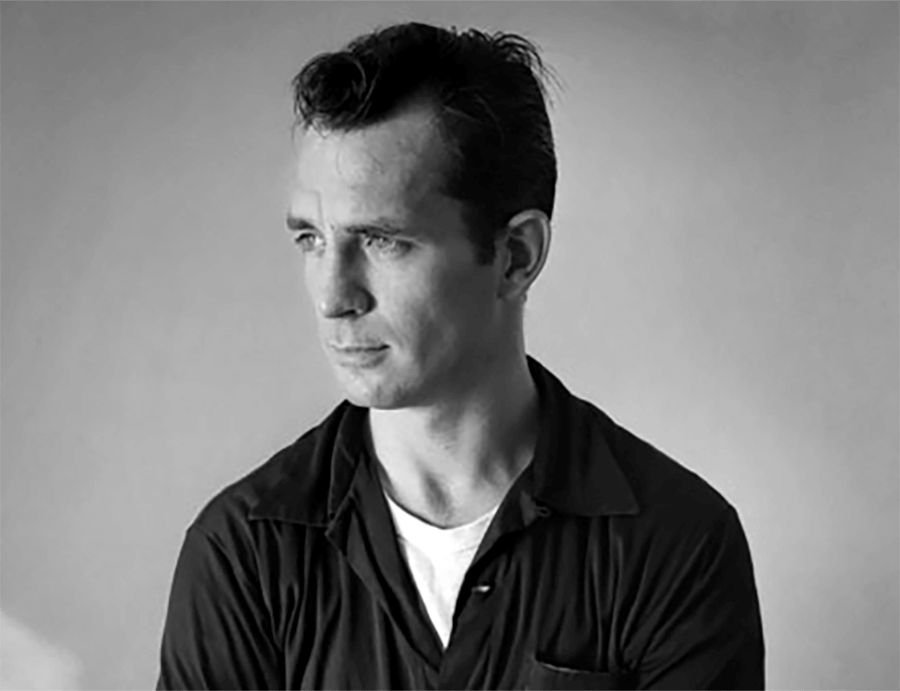

Editor’s Note: March 12, 2022 marks author Jack Kerouac’s 100th birthday. The bard of the Beat Generation lived his brief life like the burning Roman candle personalities he felt so drawn to, “a flare flung into the night sky, a shooting star . . . that fell on nothing as it sailed glimmering, evaporating into the Dark,” as Kerry Temple recounted in this 1986 Magazine Classic.

It had to do somewhat with the Shrouded Traveler. Something, someone, some spirit was pursuing all of us across the desert of life and was bound to catch us before we reached heaven. Naturally, now that I look back on it, this is only death: death will overtake us before heaven. —Sal Paradise in On the Road.

Back in my high school days, in the summer of ’69, my English teacher, a wayward Jesuit dropout, gave me a book and said, “Read this.” It was On the Road and I read it and liked it and gave it to my friend Jimmy. Jimmy read it and said “yeah” and gave it to Stuart who gave it to Mitch. And everytime we jumped in a car and streaked out onto the highway, we imitated Sal and Dean who said, “We gotta go and never stop going till we get there.”

“Where we going, man?”

“I don’t know, but we gotta go.”

It was a book to believe in then, a book about individuality and freedom and sex and fast cars. It was about America and God and Truth and Drugs — reefers and booze — and about sailing down that road, any road, racing headlong into life, arms open wide. (“What’s your road, many? — holyboy road, madman road, rainbow road, guppy road, any road. It’s an anywhere road, for anybody anyhow.”

It was about rebellion, too, and alienation, and about hitchhiking and grimy all-night diners and moonlit railroad yards, enlightened hoboes and enlightenment in Mexico. It was a book to believe in then, guru gospel truths for middle-class teenage kids in the romantic, revolutionary summer of ’69, when we were young and bold and all of life was a joyride. A book that sang of the road like wind whipping in the windows.

It was written by Jack Kerouac, and in the summer of ’69 Jack Kerouac was dying. You could say he had been dying, killing himself, since ’57 when On the Road hit the bookstores. But in the summer of ’69 — 12 years after he was declared King of the Beat Generation, after being hailed as the intellectual forebear and patron saint of the Woodstock Generation, when he was our hero, a literary James Dean — Kerouac was 47, a haunted recluse living in a St. Petersburg suburb with his paralyzed mother, in a little concrete-block house with a fake-brick façade, drinking Johnny Walker Red and Falstaff like a madman. “Call me Mister Boilermaker,” he would tell the occasional visitors.

The house would be cave-dark, the shades pulled, an eerie glare grinning from the television screen. He’d be watching McHale’s Navy or The Beverly Hillbillies, with Handel’s Messiah going full blast. Of course, we didn’t know the road had brought him here, or that when teenagers took him for rides and drove like maniacs to please him, Kerouac would crouch in fear, head tucked under the dashboard. Or that he had never really left home — even when he was a symbol of footloose-and-fancy-free, he never let go of the apron strings.

We didn’t know he was a lifelong fallen-angel Catholic who kept a St. Christopher medal pinned on his rucksack on all his aimless travels. Or that after howling for years like a Zen mystic, quoting Buddhist monks, writing haiku and Dharma Bums, he declared, “Ah well, it’s wonderful, but I really believe in sweet baby Jesus, little lamby Jesus.” He described himself as not “beat,” but as “a strange solitary crazy Catholic mystic,” sort of a 20th century John the Baptist half-mad visionary. We didn’t know Frank Leahy had once tried to get him to play football for Notre Dame, or that he had begun writing churchy poems for a Catholic magazine called Jubilee. Or that in his dying twilight years he went to church on Saturday nights to light candles and pray the rosary to Our Lady.

Who would have thought that ramblin’ Jack, who wrote more than a dozen books about his wandering ways, never learned to drive a car? After all, he had hooted philosophically on the pages of On the Road — “‘Whooee!’ yelled Dean. ‘Here we go!’ And he hunched over the wheel and gunned her; he was back in his element, everybody could see that. We were all delighted, we all realized we were leaving confusion and nonsense behind and performing our one and noble function of the time, move. And we moved!”

Back then I knew Kerouac only through the one book and I liked it. Not only did I like what it said, I liked its energy, its fullblast exuberance and joy of life, the way he used language. I kept that paperback stuffed in my jeans pocket and sometimes would sit under a tree and read passages. I still have the book: The pages are dog-eared, parts are underlined.

Here’s one of my favorites: “But then they danced down the streets like dingledodies, and I shambled after as I’ve been doing all my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow Roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes ‘Awww!’”

When I read that now, I think of flaming Jack Kerouac, I think of old Jack Kerouac and of his drive to live, his intense passion to experience it all fullflesh and with his raw, crazed soul. He was that Roman candle, a shining, a flare flung into the night sky, a shooting star . . . that fell on nothing as it sailed glimmering, evaporating into the Dark. For if Jack Kerouac was packed brimming with life, he was also crammed full of death. “It’s all a big crrrock,” he wrote at 32, when On the Road was still a crumpled manuscript stashed in his backpack. “I wanta die.”

Fifteen years later in the summer of ’69, while Jimmy and Stuart and Mitch and I — and a whole generation of restless American penny-ante wayfarers — were hungry to follow the road he had pointed out, his deathwish was coming true. He was no longer Sal Paradise chasing the Great American Dream but the author of Desolation Angels. “And I will die, and you will die, and we will all die,” he wrote. “And even the stars will fade out one after another in time.” His final prayer, he added, would be “I don’t know, I don’t care, and it doesn’t matter.”

Rarely has so much life and so much death been packed into one man.

“That last thing is what you can’t get. Nobody can get that last thing. But we keep on living in hopes of catching it once and for all.” —Sal Paradise

In 1946 Kerouac was an aspiring Serious Writer, living in New York City, hanging out with a bunch of young pseudo-intellectual literary types, digging jazz, playing with minds and books, poetry and drugs. Jack favored Benzedrine; he liked it so much he’d spent the previous December flat on his back in Queens General Hospital with thrombophlebitis, blood clots in his legs. That winter he watched his father die slowly and painfully, ravaged by stomach cancer, fluid draining from his body.

As a kid in Lowell, Massachusetts, Jack wanted to be a writer, concocting whole novels in little nickel notebooks. In New York he dreamed of being an adventurer/writer, like Wolfe, Melville, London or Hemingway. So he read and read (Hardy, Thoreau, Spengler, Saroyan, Whitman, Celine, Gide, Balzac, Proust) and ran flying at Life, racing to see and do it all.

By December 1946 he had dropped out of Columbia, been jailed as a material witness to a murder, and had married and divorced a rich society girl from Grosse Point, Michigan. He had made tires in West Haven, pumped gas in Hartford, been a short-order cook in D.C. and a reporter for The Lowell Sun. The U.S. Navy had given him a psychiatric discharge for “schizoid tendencies” (for pretending to be Samuel Johnson) and “indifferent character” (for resisting military discipline), and he had twice sailed the Atlantic with the merchant marines. He was 24.

In December 1946, Neal Cassady blew into town. He was a westerner, a freespirit with unbridled energy, a lover and a leave-her, living the wild and wooly life Kerouac dreamed about. He and Jack hit it off right away. That summer the pair headed west together, the first of several rambles they took over the next few years. Kerouac saw Cassady as the rambunctious mythical American hero/cowboy, there to lead him on the Great American Journey West. On the Road was in the making.

In 1949 Kerouac told friends he was working on a book that would define the post-war generation and trigger the cultural change he said came every two decades. Cassady played the lead as Dean Moriarty; Kerouac was his sidekick, Sal Paradise. They came out of the great American tradition of Thoreau, Whitman, John Muir, reminiscent of Ishmael and Queequeg, Huck and Jim, Natty and Chingachgook — American searchers going after something: God, Truth maybe, Sal called it “the pearl,” as in, “We suddenly saw the whole country like an oyster for us to open; and the pearl was there, the pearl was there.” Or it was some indefinable, ecstatic, illuminating experience, as when they abandon the dream of going west young man and head into Mexico: “‘Man, this will finally take us to IT!’ said Dean with definite faith.” But it didn’t; the road led everywhere but to that final, hoped-for destination. The futile quest become the dominant refrain in Kerouac’s life story.

The 29-year-old writer had attempted three versions of the road book before he sat down in early 1951, fueled by Benzedrine and coffee, and typed out — at 100 words per minute on a continuous roll of paper — his Great American Novel. Three frenzied weeks produced a 100-foot, 175,000-word, unpunctuated, single-paragraph recollection of his life on the road with Neal. “He just flung it all down,” recalls friend and author John Clellon Holmes. “He could disassociate himself from his fingers, and he was simply following the movie in his head.”

Thrilled with his picaresque chronicle, Kerouac hurried to Robert Giroux, his friend and publisher, and theatrically unrolled his long and winding scroll. The publisher rejected it; Kerouac put it away. Four years would pass, and repeated revisions made, before it was accepted in the summer of ’55.

Undeterred in the meantime, Kerouac figured he’d succeed artistically, if not commercially. Young and full of grandeur coming true, he earnestly embarked on a path of “a serious and socially significant writer.” He saw his road book as one chapter in a loftier, more ambitious project — writing the “autobiography of my own self-image” through a collection of books that would also reflect and preserve contemporary American culture as a work of art. It would be the story of one dropout’s search for meaning and truth in the underside — the bums, the “beats” and bus stations — of the vinyl-covered, bricked-up, fenced-in, chrome-glazed, Ozzie and Harriet Eisenhower days of 1950s suburban America.

His quest took him to New Orleans, Mexico, San Francisco — and away from custom, convention, conformity. There were parties and poetry readings, Buddhist texts and mountain climbs, spur-of-the-moment, let’s-go-right-now car trips, and all-night talk marathons. “Talking with Jack,” says poet Gary Snyder, “was like being in a handball court where you were playing with two or three balls at the same time. His mind worked in an amazing, fast, unpredictable but appropriate way.”

There were credos and kicks, wine, women and song. Bennies and booze. Kerouac, sensitive and shy, had a ball when he drank. The Bennies made his phlebitis worse; but, spurning any detour from his calling, he taped his legs to reduce the swelling and carried on. A bum once told Kerouac that standing on his head would alleviate the clotting, swelling and pain; and Jack, who declared the bum Buddha Incarnate, did handstands regularly. He made a life of looking, looking for satori, an intuitive, mystical enlightenment. What he found — and did not find — he wrote about.

Kerouac’s method — to catch it all in a just-this-second real sensory/subconscious flow — was free form, like a wailing jazz solo. He called it “sketching.” Poet Allen Ginsburg described it as “spontaneous bop prosody” and he encouraged his longtime friend to let his mad-genius juices run freestyle, creating a whole new, pure rush of literary expression. The frenetic outpouring of words, thoughts and feelings, Kerouac believed, was a way for truth to reveal itself — religiously, not premeditatively. “Once God moves your hand,” Kerouac declared, “to go back and revise, it’s a sin.”

At best Kerouac’s freewheeling expressions of raw life were sparkling crystalline dewdrops of robust, poetical prose; his style, challenging the old fiction/fact lines of art, may have been the genesis of New Journalism. “A totally unfamiliar new stance,” says Ken Kesey, best known for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. “We all tried to imitate it.” At worst, well, Truman Capote once told Norman Mailer (who defended Jack’s style), “That’s not writing, that’s just typing.”

In 1952 Kerouac wrote/typed Visions of Cody, another Neal Cassady story that Jack saw as the superior extension of On the Road. The same year he created Doctor Sax, a childhood good-and-evil fantasy drawn from his boyhood romps through the Lowell woods when he, cape-clad, pretended to be his hero, The Shadow.

Kerouac never let go of his childhood. His meager possessions, all tucked into his battered rucksack, included marbles, baseball cards and notes for complex statistical horserace and baseball games that he devised as a kid and played throughout his life. He reveled in, and wholebrokenheartedly missed, the toad-and-puppy days of innocence and wonder; the alternative — that oppressive, corrupt and Death-Ghost haunted grownup world — he resisted till it got him, gotcha, like the moustached villain lurking sinisterly in the shadowed corners.

In 1953, Kerouac wrote two love stories, Maggie Cassady and The Subterraneans. Two years later he adopted the Buddhist code of celibacy, worked as a railroad brakeman and wrote Mexico City Blues and Tristessa. The stories, as always, told of innocents adrift in a world of everyday evil. The beats.

But the Boy Innocent himself, who went out to drain the cup and know the stuff of legends, was getting the dregs with the highs. That only sharpened his thirst. The childhood place-of-the-heart just could not square with adult reality, the harsh disillusionment, the dying; so instead he sought deliverance, that perfect, mystical transport of self into a union with Being, with God. That’s what he meant by “beat.”

The term came from drug talk: being cheated, dealt a bad hand. Then it was broadened to mean emotionally, physically exhausted, down and out. But Jack saw these people — the bums, the drifters, those alienated from mainstream America — as possessing some wild-eyed secret peephole view beyond their neon/brick existence. In ’54 he said he had a vision, while sitting in the Catholic church in Lowell, that beat meant beatific, “to be in a state of beatitude like St. Francis, trying to love all life.”

“Jack was a seeker,” Holmes explained once to a biographer. “Jack struggled with the meaning of life. ‘Why am I alive? Why should I stay alive?’ This was his biggest quest: ‘Why should I stay alive? It’s just pain.’”

Life must’ve felt pointless and doomed — death waiting at every bend in the road. The boyhood friend killed at war; the homosexual friend who killed himself. In ’51 the laughing, talking Bill Cannastra decapitated when he stuck his head out a New York subway train. In November ’55, in Frisco, when he tried all afternoon to soothe Neal’s depressed girlfriend, who the next day jumped to a gruesome death. Jack fled to Rocky Mount, North Carolina, where Mémêre, his mother, was living with his sister, Caroline. And on New Year’s Day in ’56, sitting at the kitchen table, spiral notebook in hand, he began “a poem of death,” Visions of Gerard, a sentimental ode to the brother who had died at age 9 when Jack was 4. Exactly 30 years had passed and Jack was still trying to fathom the excruciating mystery that had separated him from his idolized older brother.

“We are all brought here to die,” Kerouac had proclaimed. He would not have children. He was haunted by deathwatch nightmares throughout his life — Gerard’s casket in the parlor, the rattling furniture, “the horror, the hanging, the guilt.” He wrote Ginsburg in ’55 that he feared he would soon go crazy or kill himself.

Even in the summer of ’56, when he was a fire lookout on Desolation Peak in the Cascades — the high country, paradise on earth. “No man should go through life without experiencing healthy, even bored solitude in the wilderness,” he had written, “finding himself depending solely on himself and thereby learning his true and hidden strength.” He played his solitaire horserace and baseball games, cooked his own meals, lugged buckets of snow to his cabin for drinking water, sang show tunes at the top of his lungs, then hollered metaphysical questions across the vast gorges at the dark, sheer face of Mount Hozomeen to the north: “What is the meaning of the Void?”

No Godhead Voice echoed from valley or summit in reply. So he wrote, “And you go out and suddenly your shadow is ringed by the rainbow as you walk on the hilltop, a lovely haloed mystery making you want to pray. But for your own poor gentle flesh no answer: your oil lamp burning in infinity.”

Then, on one of those 63 answerless lonely days, he killed a mouse; it had nibbled into a package of Lipton soup. The mouse, and memories of Gerard, left Kerouac sobbing and scared, sorry for his life’s crooked road.

Or the next winter, again for escape, back on the road, Kerouac set sail on a Yugoslav freighter bound for North Africa. A stormy voyage had the ship “pitching like a bottle in the howling void,” and then, he recalled, “a great change took place in my life, turning from a youthful brave sense of adventure to a complete nausea concerning experience in the world at large.”

Then in Tangier the opium made him reel and vomit and stare at the ceiling for 36 hours while his eyes refused to close and all he wanted was his childhood back, and his Wheaties and sunshine and his health.

By then Jack was a fragile passenger in a life wheeling roadlessly, totally unprepared for the next crazy turn.

On the Road appeared in bookstores on September 5, 1957. Kerouac became an overnight success, an instant celebrity, the hero of a new generation of restless, bomb-haunted, disaffiliated, rebellious American youth. The New York Times hailed the book as “a major novel,” its publication an “historic occasion,” and compared it with The Sun Also Rises as a generational testament.

Kerouac’s dark handsome face appeared in Mademoiselle and Harper’s Bazaar. Salvador Dali, meeting him at the posh Russian Tea Room, pronounced Jack, with his brooding good looks, “more beautiful than Marlon Brando.” Brando, it was rumored, was interested in a movie version of On the Road. Lillian Hellman asked Kerouac to write a play. He was in demand at glitzy high-brow bashes, on radio and television talk shows, on college campuses. He was mobbed by women who tore at his clothing; weeks after On the Road was published, John Clellon Holmes received 35 phone calls requesting introductions to this new literary star.

“Most books are contained,” Holmes explained. “That is, people say ‘I want to read that book.’ But when On the Road came out, people said ‘I want to know that man.’ It wasn’t the book so much as it was the man. Jack didn’t know who he was and it terrified him. For the rest of his life he never, never got his needle back to true north. Never.”

Kerouac couldn’t stand the fame he had always hoped would be his. Even on the night after Road appeared, Jack presciently dreamed of being chased by police in Lowell. He was rescued, he told friends, by “a parade of children chanting my name.” They maneuvered his escape by hiding him in their “endless ranks.”

In reality Kerouac had more to endure than the glare of the klieg lights. Six years and eight books had passed since he wrote On the Road, which he felt was eclipsed by superior work. Although other publishers eventually brought out his other novels, he was frustrated that no one cared about the Legend of Duluoz, his grand and epic saga of his persona exploring the backstreets of American life.

Then there were the critics who, after the initial fanfare, attacked the novel — “a blend of nihilism and mush,” wrote Herbert Gold in Nation, “a proof of illness rather than a creation of art.” And the talk-show hosts who presented Kerouac as a one-dimensional proponent of a thousand social ills and the cult-figure voice of the beatniks “dropping out” in Greenwich Village coffehouses. “I am an artful storyteller, a writer,” he maintained, “not a spokesman for a million hoods.”

When he appeared on Nightbeat, a popular television talk show, he “clammed up almost totally,” wrote one reporter, “looking like nothing so much as a scared rabbit.” Kerouac recalled the show: “Yeah, man, I was plenty scared. One of my friends told me don’t say anything, nothing that’ll get you in trouble. So I just kept saying no, like a kid dragged in by a cop. That’s the way I thought of it — a kid dragged before the cops.”

Yanked to center stage, billed as the avatar of a new Lost Generation, Kerouac was more lost than ever. He confided, “I’m always thinking: What am I doing here? Is this the way I’m supposed to feel?”

“The tragedy and irony,” Holmes explained, “is that he worked so very selflessly out of his genius to put down on paper, to project in the world a vision, and then when it came back to him, when it was accepted — from his point of view — for the wrong reasons, he didn’t know how to handle it. That’s what made him good. If he’d known how the world worked, he never would have broken his heart over it.”

To endure the acclaim, the readings and media demands, the guest-spot appearances, Kerouac — never comfortable around strangers — increasingly turned to alcohol as light anesthesia, bottled bravado. It was, he said, “my liquid suit of armor, my shield which not even Flash Gordon’s super ray gun could penetrate.” Its power was a delusion; his drinking and his erratic behavior (at scholarly symposia at Hunter College and Brandeis and on William F. Buckley’s Firing Line) only shortened his time in the limelight.

On the Road was on the bestseller lists for five weeks that fall, topping out at number 11. Viking Press asked Kerouac for a follow-up book, and in 10 typing sessions that November he wrote Dharma Bums, a tightly constructed little narrative laced with Buddhist philosophy. He would not write again for four years. “Too much adulation is worse than nonrecognition, I see now,” he wrote in a letter.

Fleeing the commotion that had sent him spiraling downward, he and Mémêre retreated to Northport, Long Island. She, who never read past page 34 of On the Road and who pinned holy cards to her slip, became the guardian at his door, censoring his mail and phone calls, managing his money. He set up a writing room spartanly equipped with a table, chair, typewriter, paper, light — and crucifix. But the words never came. “I asked Jack, ‘Well, how do you like fame?’” a friend once recalled. “He said, ‘It’s like old newspapers blowing down Bleeker Street.’”

As Kerouac ducked into his burrow, the whole Beat scene was hitting high tide. Greenwich Village was filling up with long-haired, goateed, bohemian hipsters; Maynard G. Krebs made the Dobie Gillis Show. Route 66, a cleaned-up, copped-out middle-American stamp-of-approval television version of On the Road, got hot in living rooms throughout the land. Beatniks became a feared, ridiculed, satirized, put down, joked about cultural phenomenon. And the man who started it all, the King of the Beatniks himself, told the editors at the Village Voice he wanted no part of this Beat fad that would soon be “as dead as Davy Crockett hats.”

“I wasn’t trying to create any new kind of consciousness or anything like that. We didn’t have a whole lot of heavy abstract thoughts. We were just a bunch of guys who were trying to get laid.” —Jack Kerouac, on the meaning of On the Road.

And so maybe the starch-collar critics didn’t value his life’s work and maybe On the Road wasn’t taught in university classrooms, but college kids were reading it well into the ’60s, when you could find it in the right bookstores — the New American Library’s Signet edition has never been out of print. Because, in the words of William Burroughs, it was “as if a generation were waiting to be written,” and Kerouac wrote it.

Kerouac was indeed the blade of the revolution’s cutting edge, first carving out notches in the ’50s. You look at what he wrote and you hear anthems for the ’60s. In 1957 he foresaw “thousands or even millions of young Americans wandering around with rucksacks, going up to mountains to pray, making children laugh and old men glad, making young girls happy and old girls happier, all of ’em Zen Lunatics who go about writing poems that happen to appear in their heads for no reason and also by being kind and also by strange unexpected acts giving visions of eternal freedom to everybody” — the flower children, the Woodstock generation, marching to Kerouac’s “beat.”

The themes are there — rebellion against the way things are, experimenting with drugs, casual sex, an exploration of Eastern religions, “doing your own thing,” spontaneous action, “experience each moment, live for now,” freedom, hitchhiking, heading West, the ecstasy of pulsing, pounding music, jazz or rock — maybe not “beat,” but “having soul,” “being real.” Like those of us who passed his book from hand to hand in the ’60s, Kerouac, too, was alienated from pat answers, mainstream values, middle-class materialism, homes all in a row. Our parents didn’t know, but we knew, what he meant when he wrote, “He had a nice home in Ohio with wife, daughter, Christmas tree, two cars, garage, lawn, lawnmower, but he couldn’t enjoy any of it because he really wasn’t free.” We could relate, it was relevant when he wrote, “I want to tell them that we don’t all want to become ants contributing to the social body, but individualists each one counting one by one.”

Kerouac was not just a writer but a voice — a prophet/advocate of a new day, a new awareness found in rejecting the old way and in the promise of individuals turned loose on freedom’s road to find “IT,” “the pearl,” or God or Truth or some new mystical vision. In that quest he was essentially and fiercely American, a frontier guide pointing the way West to an unspoiled land of opportunity. He opted to drop out rather than conform to status quo realism. He looked to self instead of institutions. He chose emotion over custom, innocence over sophistication; growing up, losing one’s youthful ideals, was a fearful prospect.

His life on the road prompted thousands of disaffected American teenage waifs to follow him west, to find themselves, to see what’s real in the underbelly, the truck stops and exit ramps of nitty-gritty nighttime America, or in the earthy back-to-nature wilderness of American not yet plasticized, sanitized, turned into a soulless wasteland. We shared his disillusionment with the complex industrial, corporate structures that squash individuals and individuality. We shared his belief that there must be more to life what lay tangibly before us, and we sought our epiphany with his roadmap in hand. We didn’t know then what he had and had not found.

You could see Kerouac’s method, his thumbprint in modern art (“FEELING is what I like in art, not CRAFTINESS and the hiding of feelings”), and his sense of antihero and alienation, liberation and friendship, on the era’s pop culture — in movies like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Midnight Cowboy, Easy Rider, Bonnie and Clyde, even The Graduate. Bob Dylan cited him as a major influence on his songwriting; Kerouac’s themes dominated the music of the age. Neal Cassady, Tom Wolfe, Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters went on the road in a psychedelic school bus a la Dean and Sal, and the result was The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test — a ’60s On the Road.

Jack Kerouac had all the birthmarks of a child of the ’60s; some said he was the godfather of the Revolution. But he would have none of it. By the time they called him Saint Jack, he was drinking at least a quart a day and mired in raunchy alcoholic decay. He supported the Vietnam War, admired William Buckley, thought LSD and the hippie movement were part of a Soviet conspiracy to overthrow the United States. He was painting portraits of the Popes and lived with Mémêre, his sister Caroline and her husband. Friends and family said he looked and sounded like Leo, the conservative working-class father whose tracks he never wanted to follow.

In 1963 Jack went to Big Sur to get away, be with friends, party. He was drinking Tokay and Muscatel, and haunted by self-hatred, paranoia and guilt. A mouse, which he had been feeding chocolate and cheese, died from rat poisoning — out of a box he had accidentally left open. Then his cat died; and Jack, who said he had always been “a little dotty” about cats because they reminded him of Gerard, had a full, complete, unhinged breakdown.

Back with his family in September ’64, Kerouac’s brother-in-law asked Caroline for a divorce and she fell dead on the spot from a heart attack. In September ’66 Mémêre had a paralyzing stroke. Jack called a childhood girlfriend, Stella Sampas, to come care for his invalid mother and her alcoholic son; Stella became his third wife on November 19, 1966.

He spent his days at home, watching television and drinking; Stella hid his shoes so he couldn’t go out and get in trouble. A lot had happened since he wrote, “The only alternative to sleeping out, hopping freights and doing what I wanted, I saw in a vision would be to just sit with a hundred other patients in front of a nice television set in a madhouse where we could be ‘supervised.’”

Although his creative powers were substantially diminished, Kerouac produced several books in the ’60s, most notably Desolation Angels. Another chapter in the Legend of Duluoz, it drew little popular attention but prompted critic Dan Wakefield to write, “Probably no other American writer has been subjected to such a barrage of ridicule, venom and cute social acumen as Kerouac. If the Pulitzer Prize in fiction were give for the book that is most representative of American life, I would nominate Desolation Angels. But we seldom recognize a real American dream when we see one.”

Then in February ’68 Neal Cassady, whom Kerouac loved as an older brother, got high at a party and hiked 20 miles down the railroad tracks outside San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, and died. “Neal’s not dead, you know,” Kerouac maintained to the end. “He couldn’t be dead. Naw, he’s hiding out somewhere, Africa maybe. He can’t be dead.”

“You’ll never be as happy as you are now in your quiltish innocent book-devouring boyhood immortal night.” — Doctor Sax.

March 12, 1922: Jean Louis Lebris de Kerouac was born into a close-knit French-Canadian family renting an apartment in the tenements of Lowell’s “Little Canada.” His father, Leo, was a printer; his mother, Gabrielle, nestled little Ti Jean into their secure, affectionate family life. There were sweet-scented kitchen mornings and laughing family suppers, punctuated by Leo’s animal noises, warmed by Mémêre’s storytelling.

Jean’s first hero was his brother, Gerard, already spotted by the parochial school nuns as a saint-in-the-making. To 4-year-old Jean, the frail, serious Gerard was a model of goodness, innocence and grace. Jean never forgot his angelic older brother rescuing a mouse from a trap or sprinkling crumbs on the window and calling to the sparrows like St. Francis of Assisi. Jean worshiped him, emulated him, stayed by his side.

By December 1925, the 9-year-old Gerard was slowly, painfully dying of rheumatic fever. As he wasted away, the house grew quiet and dark. And Jean Kerouac began then, and never stopped, questioning the source of meaningless human suffering. Months passed and Gerard’s legs grew swollen and his lungs tortured. His whimpers for God’s mercy became shrieks and sobs of agony. Jean, whose crib was near Gerard’s bed, spread holy cards about the room, but it did no good. On July 8, 1926, shortly after a visit from nuns who recorded his last words and vision of heaven, the saintly, blue-eyed Gerard died.

His left-behind little brother would never be the same; the Shrouded Traveler hovered in the air, loomed in every darkened spot. The nightmares began and never ceased; he slept in his mother’s bed, and she would never let him forget that he wasn’t as good as his brother. “You should’ve died, not Gerard,” she would yell in bitter anger.

Jean’s response was not resentment but further adoration. Gerard became his guardian angel, the mover of the writer’s hand, the author of his books. “I have followed him ever since,” Kerouac said of Gerard in 1962, “because I know he’s up there guiding my every step.”

Shortly after Gerard’s death the Kerouacs moved to a flat flanked by a funeral home and a cemetery. Jacky spent his days alone, acting out “silent movies” in the house, performing his fantasies outdoors, in the woods, along the sandbanks of the Merrimack River. He was The Shadow, he was Tom Mix. His imaginary world shielded him, delivered him from reality. By 11 he was writing sports stories for his baseball and horserace games, creating a comic strip (“Kuku and Koko at the Earth’s Core”), and had completed a novel, an imitation of Huck Finn, called “Jack Kerouac Explores the Merrimack.”

But the fantasies that delighted his days often haunted his nights. And on a warm summer evening as he crossed the Moody Street bridge, a many carrying a watermelon dropped dead in front of him. Jack followed the dead man’s staring eyes as he sailed into the dark and drifting Merrimack. Jack was devastated; at 12, he returned to his mother’s bed.

He was bright, serious and athletic in high school, a voracious reader, bashful around girls. His father was a football fan who pushed his son to excel on the gridiron. A star halfback for Lowell High School, Kerouac was recruited by Duke, Columbia and Boston College, where Frank Leahy was coaching. Leahy wanted Kerouac badly and told the darting runner he would soon be coaching at Notre Dame. Leo wanted Jack to follow Leahy there, but Jack had other ideas. He was lured by the bright lights and excitement of New York. He would never get sophisticated in South Bend, Indiana; besides, he didn’t like the thought of “being told what to think by professors in big black robes.”

Although Kerouac later suggested that not attending Notre Dame might have been one of his life’s mistakes, New York seemed the perfect stepping-off point for this writer-bound-for-glory to follow his dreams. He aspired to be a writer-about-town in the mold of Damon Runyon, a columnist for the Boston American, or a Thomas Wolfe or a Jack London. Either way, New York — and Columbia — was the place to be.

Jack loved the crowds, the sizzle and bustle, the moviehouses and Times Square. He liked riding subways and hanging out in Washington Square. He turned on to jazz, smoked a pipe and fell in with a crowd of bohemian literati — Ginsburg, Burroughs, et al — who opened doors and worlds that entranced him. It didn’t take long for football, or school, to lose appeal. One day he packed his suitcase and shuffled out past the Columbia coaches. He bought a bus ticket to Thomas Wolfe’s south, rode to Washington, D.C., “joyed like a maniac” just to look at “real southern leaves.” He was “on the road for the very first time.” And he was setting a pattern that persisted throughout his vagabonding days: He got drunk, spent a night in a flophouse and took the bus back home.

There Mémêre and Leo warned Jack that he was in with the wrong crowd, those drug addicts and bums would be a bad influence. But Jack wanted to be a writer; he didn’t want to spend is life working, like his father; he didn’t agree with Mémêre that these new wild and exciting friends would lead him down the path to his destruction.

Q. You mean Beat people are mystics?

A. Yeah, it’s a revival prophesized by Spengler. He said that in the late movements of Western civilization there would be a great revival of religious mysticism. It’s happening.

Q. What do the mystics believe in?

A. Oh, they believe in love . . . and . . . all is well . . . we’re in heaven now, really.

Q. You don’t sound happy.

A. Oh, I’m tremendously sad, I’m in great despair.

Q. Why?

A. Oh, it’s a great burden to be alive. — A 1958 interview of Jack Kerouac by Mike Wallace of CBS News.

On Sunday night October 19, 1969, Jack stayed up late reading to Stella some old letters from his father. He couldn’t sleep and lay outside on his cot under the stars, distressed because a neighbor had cut down a huge Georgia pine in front of her house. The wind in that tree had spoken to him, he said, since his sister died. He rose at 4 and went in to talk with Mémêre. They reminisced about the letters he had found. At 10:30 in the morning, bored, hot, notebook and whiskey in hand, he watched The Galloping Gourmet while eating tuna from a can. Then the pain.

He stumbled to the bathroom, vomiting blood; it poured from the massive internal hemorrhage, the ruptured veins, the collapsed liver. “Stella, help me,” he called, on his knees in the bathroom.

The ambulance took him to St. Anthony’s Hospital where doctor’s worked furiously for 20 hours using 30 pints of blood in 26 transfusions. At 5:30 a.m., October 21, 1969, Jack Kerouac died of hemorrhaging esophageal varices, the drunkard’s classic death. He was 47.

The body was taken to the Archambault Funeral Home in Lowell where Gerard had been waked. The parlor was so crowded with hippies and friends, it was difficult to approach the casket. Jack was laid out in his grey houndstooth jacket and red bow tie. Friends remarked they had never before seen his hair combed. A rosary was wound about his folded fingers and hands.

It was a traditional Catholic funeral. “Our hope is that Jack has found complete liberation,” said Father Armand “Spike” Morissette in his short eulogy. “Jack is now sharing the visions of Gerard.”

A long line of cars formed outside St. Jean Baptiste Church to follow the hearse to Edson Catholic Cemetery, where Kerouac’s grave still has no marker. As the coffin left the church, one of the local French-Canadians asked, “Who’s that?”

“Jack Kerouac,” someone said.

“Who’s Jack Kerouac?”

“Jack Kerouac was a writer,” says William Burroughs. “Many people who call themselves writers and have their names on books are not writers — the difference being, a bullfighter who fights a bull is different from a bullshitter who makes passes with no bull there. There writer has been there or he can’t write about it. And going there he risks being gored.”

“Jack was a 20th-century mythographer,” says Gary Snyder, compiling “one of the best statements of the myth of the 20th century.”

Jack Kerouac was a writer, one of a few I wish I could have known. He’s largely forgotten now; his books are mostly out of print. But once upon a time in America he spoke to a generation of restless souls with words like this:

“A new day is dawning in the blue lagoon east over Oakland there, a silent sad Coast Line truck trailer sits by a skeletal shed in the soft dawn of all America marching to this last land, this receiving California. The dew is on the road again, the new day rises on the world and on my foolish life. I loved the blue dawns over racetracks and made a bet Ioway was sweet like its name, my heart went out to lonely sounds in the misty springtime night of wild sweet America in her powers, the wetness on the wire fences bugled me to belief, I stood on sandpiles with an open soul, I not only accept loss forever, I am made of loss — I am made of Cody too—

“Adios, you who watched the sun go down, at the rail, by my side, smiling—

“Adios, King.”

Kerry Temple is editor of this magazine.