Editor’s Note: Deadly violence in the Middle East has scarred human history, erupting again with the Hamas attacks and Israel’s retaliation in late 2023. In 1987, Alan Jilka ’84, then a congressional aide, wrote of “the Palestinian problem,” its historic origins and modern manifestations, and the obstacles to a solution, both in the region and in the U.S. corridors of power.

All parties seem to agree that a single problem lies at the heart of all the strategic, political, religious and cultural conflicts that make peace in the Mideast appear impossible. All the major writings and statements of those involved — Shamir, Peres, Arafat, Sadat, Mubarak, Carter, Reagan, the Soviets, the Saudis — point to “the Palestinian problem” as the central factor in the regional stalemate.

In the wake of the 1986 American bombing raid against Libya — President Reagan’s frustrated response to terrorist strikes throughout the world — Italian Prime Minister Bettino Craxi cited “the Palestinian problem” as the major cause of terrorism in the world. A few days later the Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro’s major daily paper, addressed the same issue and came to the same conclusion — “the Palestinian problem” is the major source of terrorist agitation. But, the writer concluded, “although [the Palestinian problem] has grown increasingly more complicated since the end of World War II, it is not yet unsolvable.”

What is “the Palestinian problem”? Is American foreign policy ready to seriously pursue its resolution?

To most Americans, the Middle East seems a smoldering mass of hatred and confusion. And most American policymakers, while taking steps to ensure Israel’s security and survival, would like to leave the Arabs fighting among themselves. Americans do not fully understand the crucial issues plaguing the region, nor do they fully appreciate our power to bring about a peaceful resolution to some of the region’s main problems.

Specifically, the United States is morally on the wrong side of the Middle East debate. We are one of only a few countries in the world (a group that does not include our major European allies) that don’t recognize the Palestinians’ right to a homeland. Maybe we should note what Anwar Sadat told the Israeli Knesset in 1977, “It would not be right for you to demand for yourselves what you deny to others.” Until Israel and the United States recognize that Palestinian right, there will be no hope for lasting peace in the Middle East.

The Jews have longed for a homeland since their land was swallowed into the Roman Empire more than 2,000 years ago. Their desires were intensified by the growth of modern political Zionism during the 19th century. The movement’s founder, Theordore Herzl, wrote in 1896, “Let sovereignty be granted us over a portion of the globe large enough to satisfy the rightful requirements of a nation.” The problem was where.

In 1917 the British decided that Palestine would be the place. The Balfour Declaration, a political move intended to win American support for the allied World War I effort, established as an international goal the creation of a Jewish state on land occupied by Palestinian Arabs. A steady stream of Jewish immigrants filtered into Palestine, but the Jews and Arabs lived peacefully side by side and, 30 years later in 1947, that part of Palestine designated by the United Nations as a Jewish homeland was 60 percent Jewish.

In an ironic twist of history, the Jewish State established after World War II might not have come about without Hitler, for it was Nazi Germany that galvanized world support for a Jewish homeland. When the Jewish State was conceived in 1948, Israeli soldiers occupied lands far beyond the borders outlined in the United Nations plan. These soldiers forced hundreds of thousands of Palestinians to flee their homes. The Jews thus surrounded themselves with a hatred they had caused. Arnold Toynbee, professor of modern history at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, wrote in 1967, “The Palestinian Arabs have suffered injustice. To put it simply, they have been made to pay for the genocide of the Jews in Europe which was committed by the Germans not the Arabs.”

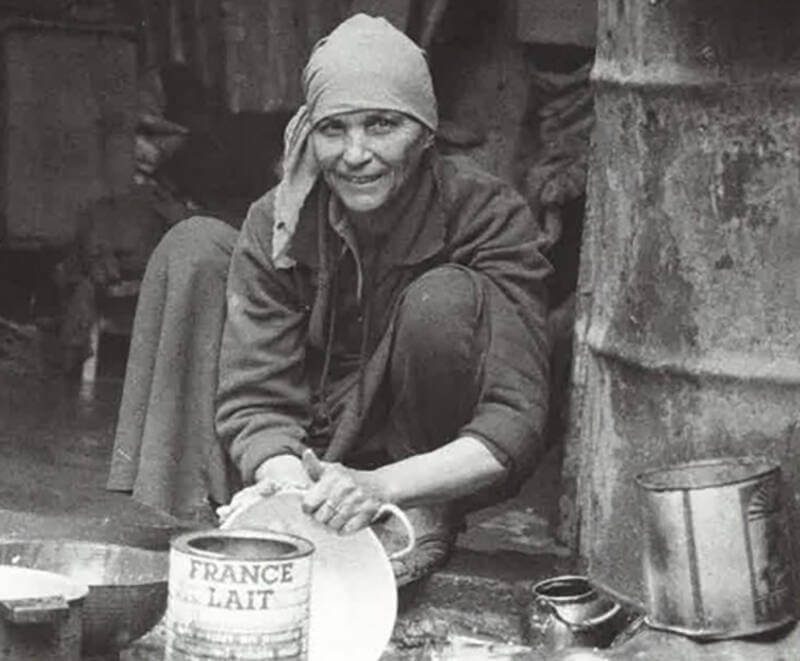

Half a million Arabs were displaced in the fighting that led to Israel’s establishment in 1948. Neighboring Arab states were unwilling to absorb the refugees, citing a lack of resources and a determination not to legitimize Israel. Most Palestinians, therefore, were forced to live in the U.N. refugee camps that are now permanent fixtures in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. The 1967 war exacerbated the problem as Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza Strip, areas inhabited by more than a million Palestinian refugees.

The entire Jewish population of Israel numbers only a little more than three million, yet Israel continues to exercise iron-fisted control over these territories. When the violent demonstrations broke out on the West Bank late in 1986 — events in which Israeli soldiers shot and killed numerous demonstrators — the news remained buried in the back pages of American newspapers. For example, during one 10-day period in December 1986, the Washington Post ran six articles on West Bank unrest. The stories reported killings of 12- and 14-year-old children by Israeli soldiers at demonstrations, but only one of the articles appeared before page 24.

The American press gives more prominent play to solidly pro-Israeli writers such as columnist George Will, who recently wrote a series of articles blasting Pope John Paul II for his 1982 audience with Yasser Arafat, the Vatican for not establishing diplomatic relations with Israel and the U.S. government for failing to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. Another column praised the 1967 “liberation” of East Jerusalem, a claim that’s ludicrous in light of the fact that, despite well-publicized new Israeli settlements, the population of East Jerusalem remains over 80 percent Palestinian.

This raises a key point regarding American thinking on the Middle East — the vilification of Yasser Arafat and the Palestinians. To many, Arafat’s name is synonymous with terrorism. American proponents of aid to the Nicaraguan Contras link the Sandinistas to Arafat and Libya’s Qaddafi, and portray them as part of a world terrorist network. But Arafat’s primary aim is his people’s right to a homeland. The concept of a “return” is also very prominent in modern-day Palestinian thinking, as it is in Jewish thought.

Perhaps the American press should give equal attention to Rabbi Meir Kahane and his membership in the Israeli Knesset (something akin to having a KKK member in the U.S. Congress) and the fact that the cause he espouses (expelling all Palestinians from within Israeli borders) is gaining support in Israel. But the American press gives greater prominence to Palestinian “terrorists.”

Why does the American public pay such selective attention to PLO terrorism? Everyone remembers vividly the massacre of 11 Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympics, but the murder of hundreds of Palestinians in Beirut in 1982 had faded from memory. In fact, Ariel Sharon, held responsible for the massacre by an official Israeli government report, remains a member of the Israeli cabinet. Israeli massacres of Palestinians at Deir Yassin and Kibya in the 1950s have similarly faded from memory. How does one explain our skewed attitudes toward Palestinians and Israel?

It is, doubtlessly, because the United States brought Israel into existence and feels bound to support it against all threats. Although Jews comprise only 3 percent of the U.S. population, a strong Jewish lobby projects a strong national attachment to Israel. Americans also share a religious, intellectual and cultural tradition with Judaism. Many of our great writers, composers and scientists are Jewish.

Nor can one overlook the sympathy for the Jews arising from the Holocaust, an experience deeply ingrained in our consciousness. Movies and books, the pursuit of Nazi war criminals, even the Kurt Waldheim story recall the German atrocities and remind us that after World War II nobody wanted the Jews. Nearly exterminated, turned away from the United States, they laid religious claim to Palestine, with Jerusalem as its capital.

Conversely, we in the West don’t understand Islam and we mistrust it. It is not part of our tradition. There is an insignificant Arab population or lobby in the United States. Arabs are stereotyped in the media — from cartoons to movies — as mysterious and cunning villains. While these factors inhibit constructive American action in the Middle East, the United States supports Israel, although nearly a third of the people within Israel’s borders are Arab — Arabs forced to live in a country where only Jews can obtain citizenship.

There is a great contradiction among world Jewry. Jews of Europe and the United States lead struggles for secularism and the separation of church and state, but they continue to support the most discriminatory and closed of nations — a society in which the ideal is racial and exclusionist, where no one wants even to talk about giving rights to Palestinians.

The Middle East is locked in tense confrontation; neither the Israelis nor Palestinians want to make peace except on capitulatory terms. Each side is too vulnerable to initiate a resolution. Only the United States has the power and prestige to bring the sides together. Unfortunately, the United States favors the Israelis, and this policy is not capable of bringing about genuine peace. But if Israel could be persuaded to recognize unequivocally the Palestinians’ right to a homeland, surely the Palestinians, like Anwar Sadat before them, would recognize Israel’s right to exist.

Anwar Sadat was a man of stature, willing to take great risks for peace; he should be long remembered for his courageous overtures toward Israel. His memory is valuable for three lessons. First, he showed that peace is possible between Arabs and Jews, dramatically illustrated by the Camp David negotiations. The second lesson is that a U.S. role in the peace process is crucial; neither side is prepared politically, militarily or psychologically to offer a compromise of its own. Thirdly, any comprehensive Middle East peace settlement must deal adequately with the Palestinian question — something Camp David failed to do.

Israel was allowed under that accord to maintain an open-ended military presence on the West Bank and retain control over such vital services as water, electricity and security. Menachem Begin’s view of “Palestinian autonomy” amounted to a very limited self-rule, and the four million Palestinian Arabs are still a people without a country, more than a third of them living under Israeli military rule.

The creation of a Palestinian state is the ideal solution for all parties involved. It would take compromise on all sides but the only avenue to peace is to respect the rights and interests of everyone involved. But that won’t come about until the American public recognizes the legitimate rights of the Palestinians.

When this story was published in 1987, Alan Jilka lived in Washington, D.C., where he worked for U.S. Congressman Dan Glickman (D-Kan.).