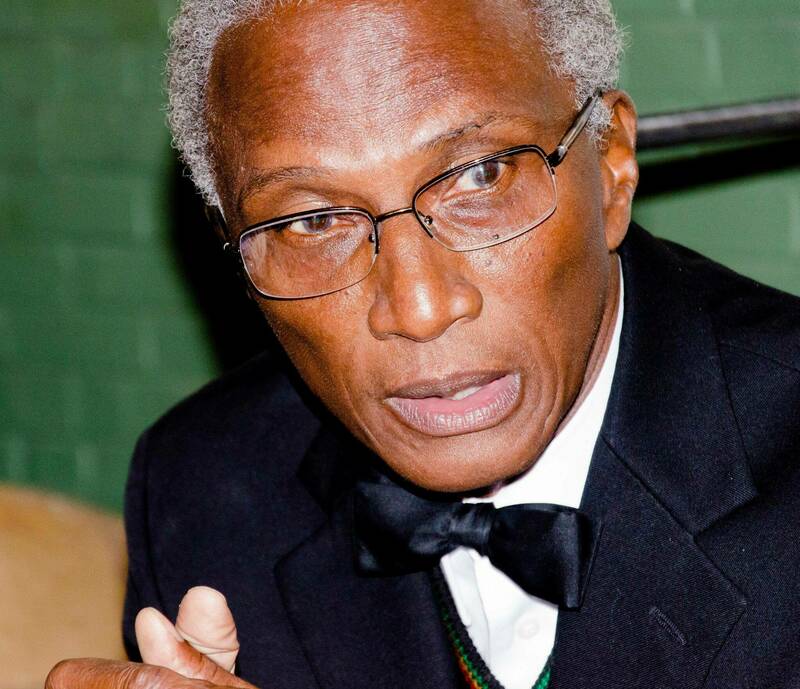

Photo by Karl D. Turner

Photo by Karl D. Turner

You’ve heard of the Harlem Renaissance. William H. Turner ’74Ph.D. grew up in the 1940s and ’50s among a lesser-known, thriving Black community in the coal country of Harlan County, Kentucky. His new book, The Harlan Renaissance: Stories of Black Life in Appalachian Coal Towns, adds to a body of work documenting that overlooked aspect of a region often stereotyped as white and poor.

During a career that took him to Winston-Salem State University, Kentucky State University, Berea College and Prairie View A&M University, Turner co-edited Blacks in Appalachia, a defining sociological text that prompted Roots author Alex Haley to say, “Bill knows more about black people in the mountains of the South than anyone in the world.”

Haley also thought Turner should tell his story in less academic language. In The Harlan Renaissance, Turner takes that to heart, writing as Haley encouraged him to do, in “a voice my Mama would read.”

What inspired you to tell this story right now?

Going way back to, say, a [1963] book called Night Comes to the Cumberlands through any number of major works about the Appalachian region, virtually none of them have focused on Black people in the mountains of the South. In the late ’70s, through my relationship with Berea College, I met Alex Haley. Alex was just coming off a mountain called Roots, and his work with The Autobiography of Malcolm X. I had published along with another fellow an anthology called Blacks in Appalachia, which is still the only book of its type, a broad view of the history of Black people in central Appalachia, this stereotypical white space. I was trying to get tenure at the time. Alex looked at it and said, “Bill, I hope you never write anything like this again. All these graphs, all these charts, all these big words, they might impress somebody back at Notre Dame, or some sociologists and demographers, but write something your Mama will read.” And so I’ve played around with it for 25 years here and there, in and out of the mountains all the time. My biggest question was, how do you find a voice that my Mama would read? My Mama’s been dead 25 years, but I got it done.

How do you bring personal experience and sociological expertise together in The Harlan Renaissance?

Over a very long period of time, I have interviewed hundreds of people. For example, just two days ago, doing a book signing in Louisville, a lady in her 90s, who her son described as “Mama has Alzheimer’s,” stood up and said to everybody, “Well, I’ve known Billy since he was born.” That lady’s 96. And so I listened to her voice. I went to all these churches. I tried my best to blend this sociological perspective with my journey with my people, as it were. My best reviews have been from people whom I knew personally since I was a child, who said, “Oh, thank you for mentioning my church. And you can remember those songs that Grandpa used to sing. And those folksy little Appalachian sayings that expressed our values, the part about us being patriotic, the part about us being very religious.” So that’s how I found my voice. I listened to my brothers and my sisters.

What was life like for Black people in the Harlan County you knew?

The fact of the matter is, I never went to bed hungry. For a man who had three formal grades of schooling, my father started working in coal mining when he was 13 years old. My grandfather on my mother’s side used to tell me, “Before I got this coal mining job where I made money, we were sharecroppers. All we did every day was looked up the north end of a southbound mule.” Then he came to the coal mining, which in the early ’30s was very steady work. And so they were able to maintain our family through that period, from 1917 until those mines began to close in the 1970s. We were very secure.

I didn’t see any Klansmen marching down the street where I grew up, because there was a kind of a camaraderie between these Black and white coal miners. They had a saying, “Everybody’s Black inside of a coal mine.” Of course, when they came out, it went back to the real Black-white schism. We understood that very well.

But all in all, our town was called the Cadillac of coal towns. I had an extremely superior education. I had teachers who had been prepared themselves in the historically Black colleges in the South, such as Spelman and Fisk, and particularly Kentucky State University, West Virginia State University, Virginia State University, many of which were impacted by a man who was a partner to Booker T. Washington. His name was Julius Rosenwald. He built 4,500 schools in the South just to educate Black people. Black people put their pennies together and matched the Rosenwald money, and voilà, there I was, being taught by teachers who went to Columbia University in the summertime.

Why do you feel school integration in Harlan County had a negative impact?

I have a chapter in my book titled, “School Integration Was Worse Than A Kick in the Head by an Alabama Mule.” I am not such a Neanderthal that I was arguing we should have stayed segregated. I’m not saying that. It wasn’t integration, it’s the way they did it. In that period, between the ’50s and up until almost the ’70s, virtually every school board in the South was old white men. And so when you’re in a little town like mine and you’re going to integrate and you have two Blacks who teach chemistry at the colored school, and then you have two whites teaching chemistry at the white school, when they combined them, who you think they didn’t keep?

These Black schools were the very repositories of the Black middle class. Because those [teachers] were generally the only Black middle-class people who weren’t coal miners for miles around. And so all of a sudden, within five years, they all moved to Louisville, they moved to Cincinnati, because they were in their 40s, they were at the height of their careers. This was devastating to these communities. When they were throwing out the dirty water of segregation, they threw out many of the babies. They threw out some of the best parts of the system. And that was these excellent teachers.

I just want to make it clear: I am quite in favor of that social canopy under which all of us should live, but at the same time, I don’t think that that canopy should just smother out the light of things that are uniquely Black in America. And to the extent that somebody tries to convince us that when you try to strengthen Black communities, when you try to strengthen Black schools, when you try to strengthen Black businesses, when you try to do anything that preserves Black culture and Black traditions, you’re somehow segregating yourself, well, as my Dad would say, that’s a crock.

Interview by Jason Kelly, an associate editor of this magazine.