A surprise that it was a surprise, even though I recall wishing away the hours of my youth to escape beyond the open windows where the groundskeeper mowed the luminance of the dandelion-besprinkled lawn of a school that restrained me from a landscape of desire. Wished hours away years later during the long drive from home with my daughter to move her into a college dorm room overlooking lawns that must have seemed nearly endless to her before her mother fell ill. Wished away the hours of uneasy visits with my wife’s aunt when she still knew who we were, and the shut window and block walls and the babbling of the innocent nursing-home inmates muffled the mower out on the cramped lawn.

A surprise, even though of course I already knew 50 years had passed. After I returned from the mailbox and showed her the announcement of my high school reunion, my wife, who has more reason than most to wonder, asked, “Where did the time go?”

I said, mainly to myself, “You tell me.”

What I didn’t say is that I was recalling a kiss with someone other than her and still was kissing someone else and was afraid the kiss must end. I could have tried to explain to Margaret that each time we had kissed during our marriage, I was kissing a teenager named Linda, or so it felt in the instant after Margaret asked where the time had gone — though it had never before seemed so.

I might have added in my defense that I never wished Margaret was anyone else and had thought of the girl only rarely during the five decades since the kiss, but when the reunion announcement arrived, tumors and surgery and radiation treatments had damaged Margaret’s brain, and the fact that my longest kiss wasn’t with her — or not solely — wasn’t a subject for shared wonder or teasing as it would have been before the cancer, when she might have asked, “Was this girl masochistic?”

These days, Margaret is unable to carry on more than a short conversation, her nouns soon withheld and lost in aphasia and distractibility, her fragmented sentences wandering or abandoned. We were standing in our kitchen, two former kidders and gropers, and beyond the windows the late summer leaves were losing luster.

We hugged.

Every family needs a stout realist, a member who considers sentimentality to be hallucinogenic, making all the more precious the memory of a kiss. Most often I’ve heard the question — Where did the time go? — asked by wistful older people speaking mainly to themselves, but never by my Grandmother Wagner. Not long after the death of my grandfather, she told me, “If I had it to do over again, I would have knocked that farming idea right out of Wagner’s head.” I heard her reminisce about her childhood just once, when we were sitting with her brother Howard in wicker chairs on her porch that faced the road and the swamp beyond, half-listening to the edacious mosquitoes, multitudes strumming and humming with desire, smothering the screens between us and the night. She said, abruptly and flatly, “Our father must have been a horrible man if I hated always to have him come home from work.” Howard didn’t respond, and she said nothing more about their father. Several years later, one of her doctors recommended surgery to remove a malignant tumor, but she declined and would explain to Margaret and me, “I think them doctors just wanna make some more money off me before I die.”

Because I knew she considered halcyon days to be a privilege of people who stayed up well past dusk, slept in past dawn and thought chocolate milk came from brown cows, I was curious to know whether her years had still passed quickly. I inquired one afternoon at her kitchen table between the shelf of knickknacks and the wood-fired cooking stove while she was attempting to fill me with more food than possible. “Oh, yes,” she said, her voice lifting and quavering for a moment, surprising me, “as fast as Wagner could eat a piece of my apple pie.”

I inherited some of her cynicism about a better past. Despite my longing to see again the dear dead who now outnumber the dear living in my memories, and though I wish I still had the physical body of my youth — and despite a girl named Linda — I wouldn’t go back if I could. My father was dying throughout my teen years, a funerary background of bedroom moaning, bottles of futile painkillers on the bedstand and dresser and eventually syringes and tiny jars of morphine glinting in incandescent light. Even if mortal illness had not claimed every room of my home as its own, emptying the refrigerator, yanking shut the curtains, hanging its self-portrait on each wall, my hometown was hardly W.B. Yeats’ peaceful, moonlit Lake Isle of Innisfree.

If there is no point in trying to explain where time goes, there is little in asking. It is similar to asking why there is a universe rather than nothing.

My Innisfree was clouded. Dampening the warmth and laughter of families and neighbors and friends, boys fought each other and men returned home sore and coughing from factories and foundries with little care that many of the women who raised the children and cooked and cleaned were bored and tired and resentful. During evenings and weekends the women kept working and the men mowed grass or shoveled snow and watched sports on television and drank, and children escaped outside or into the homes of friends, into dissolving illusions of freedom and safety. A boy who graduated from my high school before I did drove around town one night shooting into houses at random, killing a woman; a boy who graduated after me murdered 168 people by detonating a bomb in Oklahoma City.

At our 20th reunion, a classmate told me a girl we had grown up with was sexually abused by her father, and another was gang-raped by men in our community. My friend was interrupted by another classmate, a woman who wished to reminisce about happy days. So we did, the three of us. It struck me that the interloper might have overheard an inapposite conversation between classmates and was like the teacher who passed by my locker each day after lunchtime when I was in 12th grade and was pawing through a tumbling heap of textbooks, tattered notebooks, leaky pens, pencils with gnawed erasers, candy wrappers and bleeding test papers, and who, in the tumult, locker doors banging shut, students arguing, laughing, gossiping, mocking, yelling just to yell, everyone in a hurry except the couples kissing, always asked how I was doing, and nearly always I replied, “Great.”

Once I said, “OK.”

A plump, white-haired lady whose thick-lensed glasses — “Coke bottles,” some kids called them — were usually askew, she turned back. “Only OK today?”

I said, “No. You know. I mean, I’m great. Everything’s fine.”

She hugged me, and I felt somewhat better.

I hope I’ve shown I did not grow up in a particularly sentimental family or community. And yet — the kiss. Because Linda would be absent from our class reunion, we could not laugh together about our longest kiss, which has little and much to do with the tedium of my school days, my emotionally fallen hometown, my father’s suffering, Margaret’s illness, and still more of my life before and after I knew Linda. That was one reason I didn’t attend the 50th reunion. That and my dearth of courage. Another way of putting this is to note that, of course, though I try to forget, the border between life and death is as notional as any other construct. During one of our final visits with Grandmother Wagner, she lifted her blouse and took my wife’s hand and placed it on her abdomen, where the bulbous tumor stretched her skin, and asked, “Don’t it feel like I’m pregnant?” — and later that evening, as Margaret and I were about to depart the farm, the old woman held our infant daughter and kissed her on the forehead.

I wonder how I could explain to Margaret the length and fragility of a kiss that began before my first glimpse of her, standing on the opposite side of an indoor ice rink, and which lasts. Once I could have, but now? I would like to talk as we once did about our lives together and apart.

I would like to speak again of Grandmother Wagner standing behind Grandfather’s wheelchair near a window of their kitchen, crooking her arthritic knees, her love unsuccessfully hidden as she combs the few remaining white strands of hair over his sun-dappled pate. Of my dying father saying — bequeathing — to his children, “I’ve lived over 40 years, and it’s a lot of years,” and, “If you ever feel sorry for yourself, do what I did and walk through hospital wings to look in the rooms.” Of the obstetrician permitting me to watch the cesarean section after asking whether I’d ever seen much blood, and my crass reply that I had eviscerated deer, and then my cradling the newborn while I wept. Of my 2-year-old son playing an oversize Baby Jesus in the Christmas pageant at St. Philomena Roman Catholic Church and his proud 4-year-old sister escaping her parents and running from the pew and up the aisle, pointing with both arms as she hollers, “That’s my little brother up there!”

I would like to speak again of driving through an eye-blink town where I was filled with baffling joy at the sight of a couple who looked much like my parents had when they were alive and young. Of studying an old woman at the YMCA and detecting how she appeared when young; and a young woman at the YMCA, and how she would appear when old; and once again of my maternal grandparents and the tender sweep of the comb in my grandmother’s knarred hand. Of standing in a waving hayfield for several minutes of tipped awe at the grace of a large bird in a wind that was blowing negation through my body, the turkey vulture’s wings unfurled and unflapping as it floated low and looping and listed to its left and right like an unmoored autumn leaf. Of standing on a footbridge over a sunny brook and watching water striders on a flow so clear that they cast gliding, magnified shadows on the gravel bottom — and yet it appears the shadows cast the striders. Of standing on a narrow Irish beach near the scree of a cliff while waves break in the rhythm of the third chapter of Ecclesiastes. How is such a grim chapter so lovely?

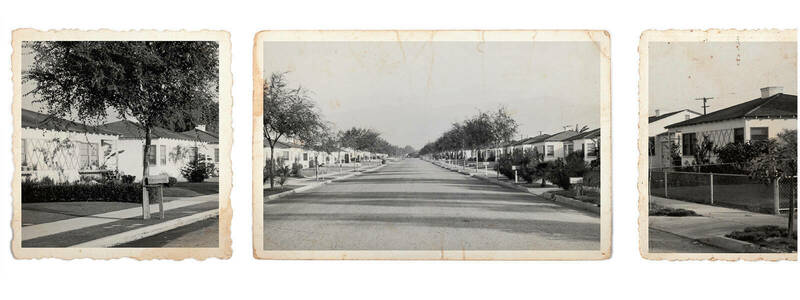

With Margaret I would like to talk of Linda telephoning me on a July afternoon back when summer vacations from school conjured eternity. About a girl inviting me to her house, and my walking the several miles past scores of small, ranch-style homes constructed with the help of the GI Bill in the decades following the vast bloodshed of World War II, past abandoned farm fields and orchards, and the cigarette butts and shards of clear and brown glass on gravel shoulders, though I saw none of these things on that day. I arrived dripping perspiration and asked to use the bathroom and there found deodorant to apply over the liberal spraying I had given myself in my bedroom after the telephone call, and hurried out to sit with Linda on the couch, the clash of my sweat and deodorants so strong it is a wonder either of us could breathe.

Her parents and sisters weren’t home, and we talked a long while, the living room becoming less the museum or store display that most such rooms resemble and more a place for actual living, and she inched closer, I think without her quite realizing it, the quiet creaking of the couch springs sounding to me like a promise before I saw the damaged image of Martin Luther King on the cover of a magazine, probably Time or Newsweek, centered on the coffee table like a trophy. She noticed my staring. “My father stabbed him,” she said quite seriously.

I suggested a walk to a bridge over the Erie Canal. We watched pleasure boats and garbage pass beneath before we returned to the house. I didn’t much enjoy the short period of kissing that followed on the couch. I broke away to ask when her father would be home, but I now think my disturbance at the slashed magazine was a good reason for kissing and more, not that there would be more on that afternoon.

I waited another two summers before I asked her to date me.

It all seems so recent to me.

If there is no point in trying to explain where time goes, there is little in asking. It is similar to asking why there is a universe rather than nothing; the best answers many of us mortals can find are to shrug and feel grateful for life. After receiving notice of our 50-year reunion, I exchanged emails with the secretary of my class and learned that 16 percent of our peers had died — more than 30 classmates, including Linda.

I can’t tell you where the time went, or why there is a universe, but maybe I can explain what it is like to realize fully, after opening an envelope and exchanging emails with a classmate, that 50 years have gone by.

On our second and final date, Linda and I went to a basketball game and a pizza parlor. “I like being with you,” she said during the ride back to her home. “Usually boys just want to talk about themselves.” I didn’t let her know I was afraid that if I got started I might tell the truth about myself. She slid close to me. Wet snow was falling by then. The kind of snow you can smell. Fast and thick. Soft ice caked the windshield wipers. Trees in white tutus performed demi-pliés all along the route as the curtain of snow opened and closed. The wipers clapped.

Her driveway was unplowed. The car didn’t have snow tires, and I was worried about becoming stuck and asked her if it was OK to kiss her good night in the car rather than walk her to her front door. The engine was running and the manual transmission in gear when we kissed. It was a long kiss. As we became more intimate time became unreal and there was never a snowstorm and my father was healthy and no gun was fired at Martin Luther King and boys from our town were not sent to Vietnam and none would die there and Linda and I would be young and alive forever and she was each girl I ever kissed and each woman I ever would kiss and she tugged me and I began to follow and as she lay back on the seat I didn’t realize my left foot was easing off the clutch pedal and the car was moving until the shuddering deafening bang when it collided with the garage door.

That’s it. That is what it was like for me to fully realize 50 years have passed.

Yet I wrote that time became unreal, didn’t I?

Linda and I are still kissing, aren’t we?

Mark Phillips lives in southwestern New York. He is the author of a memoir, My Father’s Cabin, and a collection of essays, Love and Hate in the Heartland.