Teenagers typically adopt athletes or musicians as role models, not balding English teachers. But Father Blane O’Neill’s passion for literature, so uniquely conveyed at St. Joseph’s Seminary in Westmont, Illinois, made him the idol of every kid privileged to be in his class in the 1960s.

No basketball point guard or front man in a rock band could compare when Blane would stride into the classroom with an expectant smile, pivot left into the middle of our group between two rows of desks, go down on one knee and recite from memory a passage from the work of T.S. Elliot, Mark Twain, James Baldwin or Emily Dickinson. He’d pause and let it sink in before calling on one of us for our reaction and to ignite discussion about one of the marvels of American literature.

Even a mundane lesson about sentence structure would sparkle memorably because of his dramatic flair, when a peristaltic flex of his shoulders inevitably preceded a quotation from a luminary: “I believe it was Pascal who once wrote, ‘If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter.’”

I would dutifully record the quotations in my notebook, despairing that my brain was of insufficient size to contain all the words by all the literary giants that were housed in his. Blane led me to believe that poets and novelists and playwrights held a higher rank among human beings, at a level somewhere between saints and angels, and that he was their privileged ambassador.

Ten years before our sophomore year, the Swedish Academy awarded the Nobel Prize for literature to Ernest Hemingway, “for his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea.” Hemingway’s classic novel featured the three-day struggle of Santiago, a Cuban fisherman, to catch and kill a marlin that was so big he had to lash it to the side of the boat where it was attacked and eaten by sharks on his journey back to his home port.

The day Father Blane lectured about it, he dramatized the climactic episode in the front of our classroom by imitating Santiago, after losing the fish, trudging up the hill to his fishing shack in the Cuban village, carrying his skiff’s tall wooden mast over his shoulder.

“What are you reminded of?” Blane asked, his arms still raised and balancing the “mast” on his shoulder.

The answer he was seeking from us 15-year-olds was that Santiago evoked the last act of Jesus Christ carrying the cross up to Calvary where he would be crucified and die. And that Hemingway’s thematic implication was that since Christ’s redemption was being jeopardized by a violent and warring world, that man’s purpose in life, and the key to our only fulfillment, is to persevere in a heroic struggle.

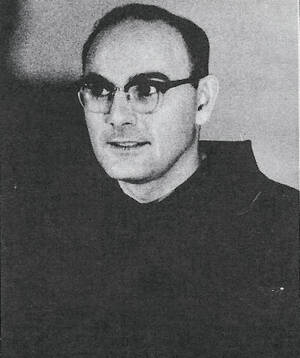

Though it was close to 60 years ago, I can still picture the bespectacled Blane, who died in 2017, in his brown Franciscan robe, carrying the invisible cross from one side of the room to the other, so profound and lasting an impact did his lesson have on me. And Hemingway, of course, with his spare, brawny sentences about fishing, hunting, camping and bullfighting, was not a hard sell to this teenage angler and aspiring writer.

Twenty-five years later, I referenced the same episode from Old Man and the Sea in a night class I was teaching at College of DuPage. It was a seminar in American fiction with 30 students. We had read Hemingway’s short stories “Hills Like White Elephants” and “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place.” I tried to recreate Father Blane’s dramatization to underscore the author’s command of metaphor and symbolism.

I did not possess Blane’s sonorous voice. Nor his thespian gift. But what I did have was confidence that Blane’s lesson would land.

Bill Hillmann was one of the 30 students in that class. He was not outspoken at the time, and it wasn’t until years later that he told me how the class got him so interested in Hemingway that he became obsessed with the author and his stories.

Hillmann, however, did not just want to read Hemingway’s work. He wished to experience it, and also to become a writer himself. And the most direct route to his goal, he determined, was to visit Spain, the setting for many of Hemingway’s books and short stories, and to run with the bulls in Pamplona in the tradition made famous in The Sun Also Rises.

Like a method actor, Hillmann, a gritty Chicagoan, wanted to test himself against Hemingway’s belief in bravery and “grace under pressure” as aspirational ideals, and he would participate many times in the annual rite that preceded the bullfight in Pamplona. He was gored twice, severely injured, chronicling his experiences in two books: Mozos: A Decade Running With the Bulls of Spain and The Pueblos: My Quest To Run 101 Bull Runs In The Small Towns of Spain.

Hillmann would continue to “follow Hemingway’s ghost,” as he described it, acquiring a doctorate in literature and becoming a professor of English at East-West University in Chicago, where he now lectures his own students about great literature and Ernest Hemingway. His unique career path was featured last November on the The Whole Story with Anderson Cooper in a documentary called Seeing Red: Running with the Bulls.

Thus, the passion and method of the marvelous Father Blane in 1965 reverberates through half a century and multiple generations, still captivating students at East-West University in 2024.

It is just one of countless examples manifesting the importance, the reach and the lasting influence of inspirational teachers in everyone’s lives.

David McGrath, an emeritus English professor at College of DuPage, is the author of Far Enough Away, a collection of his work. His essay “His Intimacies with Lake and Stream,” published in this magazine, was cited in Best American Essays 2022. Email him at mcgrathd@dupage.edu