I’ve long thought I enjoyed a moral “Get Out of Jail Free” card regarding the Vietnam War, especially after reading Tim O’Brien’s 1990 novel, The Things They Carried. Born in 1940, I never had to confront the anguished choices that so many men born a few years later than me would have to face. I was inducted into the U.S. Army in February 1962 and honorably separated three years later, having turned my draft board’s call during simpler times into a career move: I enlisted an extra year in exchange for guaranteed training as an operating room technician in the Army Medical Corps.

With my basic needs met — “three hots and a cot” — I could squirrel away enough money to return to college when I got out. The medical training readily secured me a hospital job in civilian life. By spring 1965, a few months out of the Army and a now third-year student at Duquesne University, I was protesting the war in the streets of Pittsburgh.

For me, this was an easy, necessary choice, an assuaging of growing moral anguish about that escalating war. I had already met my draft obligation. As long as my protest stayed within the law, I could soothe my tormented conscience into feelings of righteous virtue, however briefly. I felt pride in exercising my democratic rights — in the camaraderie, too. I risked very little.

Not so for Tim O’Brien. Arguably the greatest American novelist to write of that war, O’Brien had no such moral freebie. The stakes were much higher by the time his draft notice came.

Six years my junior, having just graduated from Macalaster College, O’Brien was called up in the summer of 1968. More than half a million American troops were in Vietnam. The My Lai Massacre, in which American soldiers killed hundreds of unarmed Vietnamese civilians in a single day, had already occurred but hadn’t yet come to light. Young men were burning draft cards, fleeing to Canada or Sweden, going to jail.

O’Brien, too, had protested the war, had written editorials against it in the campus newspaper while serving as student body president. But in the end he obeyed his draft call, served in combat, and wrote great literature out of the experience.

I’ve never forgotten the narrator’s closing line to “On the Rainy River” from The Things They Carried: “I was a coward. I went to the war.” It’s the most painful, morally fraught oxymoron I’ve ever encountered, a minor koan. Passing years only increased the weight and bite of those words, once I learned O’Brien had been an infantry grunt in Quang Ngai Province where the massacre had taken place months before. He served in the same unit, different company, as the perpetrators of that heinous war crime.

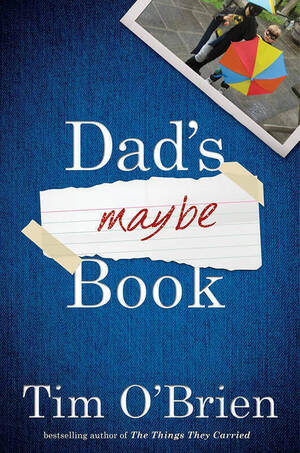

When I discovered O’Brien had shed fiction’s protective cloak to write a love-letters memoir to his two late-in-life sons, Dad’s Maybe Book (2019), I was all in. What might such a courageous quasi-draftee-coward who’d written such harrowing fiction about the Vietnam War say to his sons in straight-out nonfiction prose?

Father-to-son books form a distinct subgenre in American literature. Its parent, Benjamin Franklin, wrote in his Autobiography of his “bold and arduous project of arriving at moral perfection,” reproducing a scorecard of 13 virtues on which he examined himself each day, making tick marks in the corresponding box for each offense against them.

O’Brien’s loving, heart-rending memoir of parenthood, brimming with 16 years of daily life with his two sons, reveals the core of his parental values on page three, striking a simpler note than Franklin’s. “I yearn to witness your first act of moral courage,” he wrote in 2004 to his infant son, long before he knew his “letters” would become a book.

A parent myself, I cannot say I ever consciously yearned for such a specific spiritual goal. But wouldn’t humanity — wouldn’t the planet itself — evolve to a far healthier condition if every parent aspired to such an agenda?

In more than 300 pages, Dad’s Maybe Book rewards readers with ample autobiographical information to understand how this Vietnam veteran and extraordinary writer — O’Brien won the National Book Award in 1979 for Going After Cacciato — arrived at such an ambition. Chapters titled “Home School” assign homework to Tad and Timmy, including readings of Hemingway, Melville’s Billy Budd, and, my favorite, a field trip, an eight-mile march with their mother. She’ll issue “no weapons or ammunition,” he writes, “on account of your youth.”

After the march, the boys are to write a five-page essay on the topic, “Is war glorious?”

Among many treasures of this extraordinary book is deep respect for — almost a seminar on — Ernest Hemingway. O’Brien’s greatest insight into his giant literary predecessor, in the five “Timmy and Tad and Papa and I” chapters, is how distant combat is from much of Papa’s fiction. There is “no actual immersion” in the “sustained, slogging, minute-by-minute, here-and-now actualities of man killing man.” Hemingway’s verbs betray him: Nick Adams (In Our Time) “potting” German soldiers at a great distance — “sounds like target practice”; Frederic Henry (A Farewell to Arms) “dropped a fleeing soldier” and “may as well have shot a plastic duck at a carnival.”

Neither O’Brien nor his fictional soldiers “potted” plastic ducks. They were intimately entangled with jungle and peasant village death. They killed people. They died. “Killing people,” O’Brien writes of Frederic Henry, “is neither his job nor his spiritual burden.”

O’Brien carries immense spiritual burdens. He shares them with us as he shares them with his sons. He wants his sons to find the courage and vision to think deeply and act accordingly on what their father has learned. Us, too. We all need to awaken to moral courage, and not just in wartime.

James McKenzie, professor emeritus of English at the University of North Dakota, lives and writes in St. Paul, Minnesota. His occasional essays for Notre Dame Magazine include “The Redeeming Grace of Manual Labor.”