Lately I’ve been thinking about my friend, Walter Ciszek, a Jesuit priest whom I never met and who died in 1984 when I was 11.

I know little about Father Ciszek, a man who at my age of 46 was suffering more in a typical day than I may expect to endure in my lifetime, but he did me a remarkable spiritual favor once, and that, in my book, makes him my friend. The core of that favor has stuck with me, and this past week, as global events made it even more abundantly clear that none of us is going anywhere for a while, I got curious about what I’d forgotten: the outer contours of that favor — a simple insight dearly bought — that I had allowed to dim and fade with time.

If you don’t know Ciszek, I could not do a better job of introducing him to you than America, the Jesuit magazine, did for its readers in 1964, five months after the weary, bewildered priest stepped off the airplane that flew him home to the United States following nearly a quarter of a century in Soviet prisons and supervised labor:

“He had been officially presumed dead. His fellow Jesuits had said Masses for the repose of his soul. If you can imagine the shock — and then the joy — relatives and friends felt when news came that he was still alive, you begin to get some pale inkling of the apostles’ joy and exultation that first Easter morning, when at last they dared to believe the news the women brought them from the tomb.”

It’s hard to imagine a better modern — and, let’s be sure to say, merely human — embodiment of the resurrection than Walter Ciszek. Born in 1904, the son of Polish immigrants left behind the youth gangs of his Pennsylvania mining town to join the Jesuits, then passed his early 30s in Rome studying to become one of Pope Pius XI’s missionaries to Russia. But that Easter stuff is for next week. This week, as tens of millions of Christians the world over contemplate what was until recently unimaginable — Holy Week without confession, Mass, communal prayer, the sacraments — it is the Good Friday of Ciszek’s life that got me thumbing through his book again.

You can read the Cold War noir version of Ciszek’s hopeless exile in With God in Russia, the memoir he published in 1964. That’s the what, where, when and how of the new priest’s assignment to eastern Poland on the eve of World War II, his clandestine entry into Russia to attend to Polish refugees, his arrest by the Soviet secret police, the five years he barely survived under interrogation and in solitary confinement in the lived nightmare of Moscow’s Lubyanka prison, the decade he’d serve out in the Gulag for “espionage.” Eight more years would pass under a series of what amounted to house-arrest work assignments in the industrial wastes of central Siberia before Ciszek and another American were shipped back to the U.S. in a one-for-one exchange with recently arrested Soviet spies.

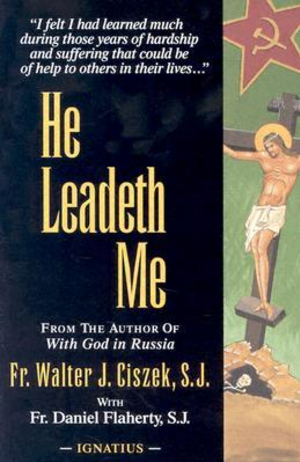

“Yet, to be perfectly honest,” Ciszek confided in the summer of 1972, “that was not the book I wanted to write. I felt that I had learned much during those years of hardship and suffering that could be of help to others in their lives.” So the priest once again revisited his 24-year ordeal to try to capture the scraped, frosty, tormented soul of his experience. The result, He Leadeth Me, is a stark literary beauty — and a spiritual field guide to any life lived in lockdown.

I began reading this second book during a weekend silent retreat at Moreau Seminary three years ago. My burdens, which seemed legion, were so mundane in the light of Ciszek’s prolonged passion that I’m embarrassed now even to mention them. Maybe you know the feeling? Yet we’re the reason for the priest’s take-two: You and me and the things we struggle with in the quiet minutes of our lives. “Through the long years of isolation and suffering,” he wrote, “God had led me to an understanding of life and his love that only those who have experienced it can fathom. He had stripped away from me many of the external consolations, physical and religious, that men rely on and had left me with a core of seemingly simple truths to guide me.”

The one that meant the most at the time, that favor I mentioned, comes early in the book, when Ciszek and another plainclothes priest, fearful of being turned in to Russian authorities by spies or the Poles they’d come to serve, slip into the forest yet again to celebrate, on a tree-stump altar, the Mass they’re afraid to offer in their camp. Wrangling over what God might want them to do, the men realize together that their “dilemma” is of their own making. Over several pages, Ciszek unspools their epiphany, then comes to this truth:

“To predict what God’s will is going to be, to rationalize about what his will must be, is at once a work of human folly and yet the subtlest of all temptations. The plain and simple truth is that his will is what he actually wills to send us each day, in the way of circumstances, places, people, and problems.

“The temptation,” he continues, “is to overlook these things . . . precisely because they are so constant, so petty, so humdrum and routine, and to seek to discover instead some other and nobler ‘will of God’ in the abstract that better fits our notion of what his will should be.”

That was Ciszek’s favor to me: an idea of God’s will that forces us out of our daydreams and delusions of who we think we’re supposed to be and into the immediate and the tangible — what’s right in front of our faces. Brutality taught Ciszek the lesson over and over again. For me, the needs, the annoyances, the crying child, the exhaustion, the unpaid bills, the anguished teenager, the irate neighbor, the miscommunications, the lack of inspiration I suffered back then were God’s will, as are those things today, as are the joys and satisfactions that often tiptoe through my life so imperceptibly that I miss them altogether, like the magnolia blossoms I can see right now from the window of my makeshift attic office.

The resolve to be a priest, come what may, sealed Ciszek’s fate: Imprisonment, isolation, beatings, humiliation, the loss of nearly everything down to his sense of self, soon followed. But so did the wisdom, and the freedom and power to share it. The Soviets excelled at finding new ways to break Ciszek’s spirit and separate him from God, yet he prayed the Mass each day from memory in the dark, dissociative silence of his Lubyanka cell. In reading those chapters, I thought of Tenebrae, the old rite late on the night of Holy Thursday when, the doors of the empty tabernacle left open and lights in the church gone out, the faithful wail and pound the pews.

Weeks ago, when our churches closed in the campaign to halt COVID-19, our Red Army, Christians entered into a Good Friday of long and uncertain duration. A friend reminded me that the Church itself is a sacrament — grace in this instance taking not the form of bread and wine but of a sacrifice of the most fundamental prayers of our faith, made in solidarity with the world of which we are a part, one which is suffering greatly. We are isolated, not unlike Father Ciszek. Stripped of the Eucharist, of community, of the chance even to perform most works of mercy, we have momentarily lost those “external consolations” we have come to rely on. Yet we still have memory, prayer and simple truth, the spiritual food and tools that sustained a forsaken Jesuit through his night of impenetrable shadow.

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.