I spent my first year of graduate school at the University of Iowa traveling between Iowa and Nicaragua, a Central American nation that was at war with mine. It was 1985. The United States government had supported the Nicaraguan dictator, Anastasio Somoza, for a decade and was trying to overthrow the new Sandinista government. I wanted to write about it. As I was naïve and idealistic, those few months living amid the Sandinista revolution were transformative for me.

I soon learned that it was not possible to write about the war in Nicaragua without writing about the Catholic Church, as the Iglesia Popular, the Church’s progressive wing, had been instrumental in Somoza’s overthrow.

At the time, many voices in the Church throughout Latin America espoused “the preferential option for the poor” — a priority given to the needs of the poor and marginalized. The term stemmed from a landmark 1968 conference in Medellín, Colombia, where the Catholic bishops embraced a theology of liberation and Christian “base communities” in which believers would read the Bible more contextually as a lens on their own poverty and political oppression.

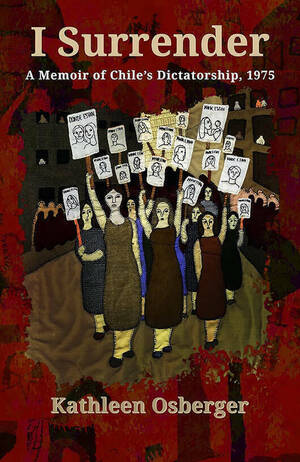

Much of this history came rushing back to me while reading Kathy Osberger’s gripping new book, I Surrender, A Memoir of Chile’s Dictatorship. In July 1975, the author, a newly minted Notre Dame graduate, became a part of a fledgling initiative –– the Latin American Program in Experiential Learning –– which sent students to volunteer for a year in poor parish communities in Chile. Osberger was assigned to teach in a grade school in Santiago and live in a convent with several nuns from the School Sisters of Notre Dame.

She knew that Chile’s then-president, General Augusto Pinochet, was a dictator swept into power two years earlier in a coup that included the assassination of the democratically elected president, Salvador Allende. She also knew that the U.S. military and the CIA had helped plan the coup.

This dangerous reality hit home upon Osberger’s arrival in Santiago. She noticed her new housemates were nervous and deeply worried, but she didn’t know why. It turned out they were hiding Sergio Zamora Torres — a key opposition leader ––for weeks after his escape from the government’s Directorate of National Intelligence, the DINA, a ruthless security force. The nuns were risking their lives to shelter Torres, and Osberger knew it.

Her housemate, Sister Bernadette Ballasty, explained, “The DINA held [Torres] in custody and tortured him with multiple burns. When they took him out to finger a man they wanted to arrest, he escaped.” Ballasty described Torres as “a brave but crumbling man, who prowled the house like a cat, finding terror in every shadow.”

These circumstances provided Osberger’s sobering introduction to the perilous five months she would spend with that community of nuns, priests and lay leaders in Santiago, many of whom became her close friends and confidants.

The sisters “lived their lives prophetically,” she writes. “Faced with a moral order of systemic repression, they were willing to act boldly. From what I could see, the Church was part of a massive act of faithful disobedience against the dictatorship’s death-dealing tactics.”

I Surrender is organized somewhat chronologically and includes some political history of the region, but much of the text concerns a single month: November 1975, a time of intense repression by the Chilean security forces.

In the middle of the night of November 1, during observance of el Día de los Muertos, DINA agents with machine guns burst into the convent, looking for Sister Helen Nelsen, the mother superior, who was staying in a distant barrio. Rosita Arroyo, Osberger’s colleague and friend, lied to the men, saying that Nelsen was “away at the coast.” Next they asked if anyone knew Sheila Cassidy, a British doctor who had been treating a wounded MIR fugitive in the house.

“I do,” Osberger said, realizing Cassidy was in imminent danger.

“You’re coming with us,” responded the tall, blue-eyed, light-skinned DINA commander, who spoke perfect American English. (Osberger later reveals the identity of the commander as Michael Townley, a notoriously brutal CIA agent.) Blindfolded and forced into a waiting car, Osberger was interrogated by three machine-gun wielding DINA agents as they cruised around Santiago and tried to force her to lead them to suspects they hoped to arrest.

Finally, and miraculously, she was released at the SSND house, after being forced to sign a paper saying she had not been harmed.

Osberger’s description of her kidnapping and interrogation is charged with sensory detail and emotionally anchors the memoir. In those few pages — and hours — the personal and political become one thing, and the reader, too, feels like a hostage to the narrative’s unfinished plotline. The scene, as Osberger tries to mentally prepare herself for torture and death, also illuminates the depth of her commitment to her community.

But I Surrender is equally about Osberger’s colleagues in the struggle — the nuns, priests and teachers who worked alongside her and served as her mentors, taking this young American under their wing, sharing their dangerous love and risky faith. The author carefully develops her portraits of each person — Arroyo, Cassidy, Nelson, Father Gerardo Whelan, CSC, ’51 and others — weaving each fragile yet resilient life into her story, her account of a volatile period in Chile’s history.

In the end, Osberger’s memoir tells a story both old and new: a small, committed faith community speaking truth to power, giving voice to the voiceless, choosing God’s love over all things.

Tom Montgomery Fate teaches writing part-time at St. Francis University in Joliet, Illinois, and is the author of six books of creative nonfiction, most recently The Long Way Home, a collection of travel essays.