On move-in day in September 1969, freshman Kit McClure arrived at Yale University with her trombone. Her new classmate, Lawrie Mifflin, brought her field hockey gear.

As far as Yale was concerned, such luggage didn’t matter for its first coed students. No women would be allowed in the marching band and there certainly wasn’t going to be a women’s field hockey team.

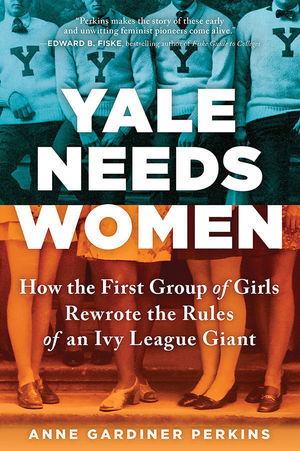

Crudely put, Yale was interested mainly in the women’s sexual presence. If the women were available as potential higher-quality partners for Yale men, they were doing their job on campus. That is the key message put forth in Yale Needs Women, by Anne Gardiner Perkins, whose book chronicles Yale’s clumsy transition to coeducation.

This book is well-researched almost to a fault. We learn more than enough about the indignities the first 200 coeds faced as Yale reluctantly scooted its men sideways just enough to give the women a home. The set-up is this: Yale was founded in 1701 and has sent its alumni into the upper crust of society ever since. But in the 1960s, the university was losing some of its luster, in part because Yale students were unhappy with the social scene.

The solution had been to bus women in from area colleges for weekend trysts. Basically, these potential pillow partners were led into mixers, where drunken Yalies would do their best to pounce and conquer.

(Don’t judge too quickly. The same approach was used in the 1970s at Notre Dame. We called them cattle drives.)

Kingman Brewster, Yale’s president at the time, had met his own wife at one of those mixers, and he figured the system worked. He saw no need to have women on campus to live and learn. Brewster defined the college’s mission as preparing 1,000 men per year to become national and international leaders. If Yale were to replace 200 men with women, he felt, he would be preparing only 800 leaders per year.

“The blindness to women’s potential as leaders was not Brewster’s alone,” Perkins writes. “Judging by Americans’ choices at the polls, he was right in step with his era. In the fall of 1968, all 50 of the state governors were men, as were 99 of the 100 U.S. senators and all but 11 of the 435 members of the U.S. House of Representatives.”

In September 1968, Ivy League rival Princeton got Yale’s attention with a study finding that female students were “vital to Princeton’s future.” It had been commonplace for applicants to turn down admission to Yale after receiving an offer from Harvard. But if Princeton had women, would the next batch of boy wonders choose it over Yale? What was the world coming to?

Two months after the Princeton study was released, with Brewster’s unhappy acquiescence, the Yale faculty voted 200-1 in favor of coeducation. Brewster went into hurry-up mode with an announcement that the first women would arrive the following autumn.

Mistakes were made. Little consideration was given to the pioneering women’s social needs. The main lament that first year among the women was they felt isolated from each other and had trouble making friends. Many felt the answer was to enroll more women — specifically, to have a gender-blind admissions policy that would give all applicants an equal chance.

More troubling, safety was a huge issue. A few members of the first female class were raped and many others were harassed. Each day brought reminders that women were at risk in a male world.

Despite outright bullying, the first women averaged higher grades overall than the men. Big deal, coeducation opponents said. The purpose of a Yale education was to create leaders, not intellectuals. And traditional campus organizations all continued to be controlled by men.

This good-old-boy disdain for intellectualism was reinforced 42 years later when George W. Bush, a 1968 Yale graduate, joked in a commencement speech at his alma mater, “To those of you who received honors, awards and distinctions, I say well done. And to the C students, I say you, too, can be president of the United States.”

Yale’s first women found other ways to lead. They started women’s rights groups, and they thrived in drama clubs and a few other organizations where they were welcomed with open arms. Ultimately, McClure used her musical talents by forming the New Haven Women’s Liberation Rock Band, while Mifflin rounded up enough women interested in field hockey that Yale grudgingly made it a varsity sport. Both ended up enriched by their experiences, good and bad, at Yale.

Yale Needs Women is informative but not particularly well written. I expected to feel a greater connection with the main characters — the half-dozen women that Perkins focused on, for sure, but also Brewster. At the time, he was the most well-respected university president in the country, though folks here would argue a strong case for Notre Dame’s Theodore Hesburgh. Some thought Brewster’s next step would be into the U.S. Senate or even the White House.

Brewster’s own education had come at an all-boys prep school, followed by all-male Yale and all-male Harvard Law School. Like a lot of men in his generation, he simply wasn’t prepared to deal with bright and tenacious women.

I can’t escape a male perspective. Reading this book, I wondered if Father Hesburgh, who I admire, would have been similarly savaged for missteps that occurred here in 1972. For example, in Notre Dame’s rush to admit women after its expected merger with Saint Mary’s College failed, the university ended up with too few dorm rooms. For many freshman men, their first experience on campus was sleeping in prison-style beds crammed into study lounges.

As a member of Notre Dame’s first coeducated class, I was an eager reader of this book. It reinforced what I had witnessed on our campus, how the women had arrived here strong and smart, becoming even better after their walk through the fire. My classmates, too, endured the cowardly catcalls, the unwanted attention from lovelorn men in the dining halls and the constant judging of their physical appearance.

At the same time, I remember a campus where boys were supposed to become men through cruel, traditional, dog-eat-dog competition. If we were to get to medical school or law school or whatever, it mainly would be through our own grit and determination.

Everyone experiences college differently, but like my classmate Rudy Ruettiger, I did not feel nurtured here. College wasn’t like that then. Like the first Yale and Notre Dame women, people wanted me to quit. I had to overcome.

One of the lifelong friends I made here once told me, “Notre Dame is where your dreams die.” A bit kinder, I would say it was where your dreams had to change.

It’s unfair to prosecute Yale or Notre Dame, or Brewster or Hesburgh. As my mother would say about the Great Depression or World War II, that’s just the way things were then. I wanted nurturing? America was shipping people my age to Vietnam and blaming them if they came home wounded or dead.

The world is dangerous now, and few of our journeys are easy. Still, it’s better than it was. On our good days, we are recognized as more than our body parts and, if it’s your choice, anyone is welcome to bring their trombone or hockey stick.

Ken Bradford is a freelance writer and former reporter at the South Bend Tribune.