On that May Sunday 40 years ago, the worlds of Washington, D.C., and Hollywood came together on the Notre Dame campus in unforgettable and historic ways.

In a production worthy of a Cecil B. DeMille or a Steven Spielberg, “Commencement Exercises” on May 17, 1981 officially made 1,977 undergraduates and post-baccalaureate students alumni of the University. These new degree holders were joined by 11 honorary degree recipients in the Athletic and Convocation Center.

For much of that afternoon, eyes at the ceremony trained on one person. Ronald Reagan, the 40th president and the year’s Commencement speaker, was making his first trip outside the nation’s capital since recovering from what the world later learned was a near-fatal assassination attempt 49 days earlier.

To anyone with even a passing connection to Notre Dame, Reagan represented more than the nation’s highest office. He also was “the Gipper,” the former actor who portrayed Irish football star George Gipp in the popular 1940 movie Knute Rockne All American.

As it happened, 1981 was the 50th anniversary of Rockne’s death in a plane crash. The actor who starred as the immortal Notre Dame coach in the biopic, Pat O’Brien, was also on stage that day and, like Reagan, an honorary degree recipient. The Rock and the Gipper were reunited not on a football field or a Hollywood movie set but at an academic ceremony that brought some 500 journalists to campus.

Planning for this Commencement began early in 1981, just days after Reagan was inaugurated. Notre Dame’s president, Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., called on a friend to call on a friend to see if the new president would be amenable to participating. Hesburgh asked publishing magnate and former U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom, Walter H. Annenberg, to deliver the university’s invitation. Since the 1960s, the Reagans had been guests at the Annenbergs annual New Year’s Eve party at their 200-acre estate at Rancho Mirage, California.

The Annenbergs, Walter and Leonore, were also close friends of both Hesburgh and Notre Dame’s longtime executive vice president, Rev. Edmund P. Joyce, C.S.C. The couple’s philanthropy enhanced the university, including the construction of the Annenberg Auditorium in the Snite Museum of Art.

Less than a month after his inauguration, the president agreed to speak at Commencement, making him the fifth U.S. chief executive to be recognized with an honorary degree on campus. Three others have followed since then.

Notre Dame’s president sent Annenberg a thank-you note for his “ambassadorial function.” The priest, then completing his 29th year at the university’s helm, turned philosophical conveying his gratitude: “It’s good to have good friends who can accomplish what they set out to do. When someone asked me the other day what I like in my friends, I said ‘effectiveness.’”

The late March assassination attempt created an anxious time in America — and for those responsible for Notre Dame’s Commencement. Reagan, a fit 70-year-old, recuperated enough over the first two weeks after the shooting to work on a limited basis, beginning on April 13. Fifteen days later, he delivered an address on his administration’s economic recovery program to a joint session of Congress that, to a great extent, also projected his physical recovery.

Commencement day dawned sunny and clear. Making my way to the ACC for the first of many such ceremonies as a Notre Dame faculty member, I was struck by the abundance of police and security personnel outside and inside the building. Just a few entrances allowed entry, each equipped with metal detectors. The gates not providing access were chained to prevent anyone from leaving the ACC except through a guarded access point.

Besides the beefed-up law enforcement presence, I was later told that full trauma and surgical teams of every medical specialty were on duty at the two local hospitals. Though standard protocol during a presidential visit, in 1981 there was heightened concern and apprehension. In addition to the attempt on Reagan’s life, just five days before Commencement, Pope John Paul II had been shot and severely wounded in St. Peter’s Square. Fear of a copycat attack worried the Secret Service and others.

As many as a thousand protesters demonstrated against Reagan’s policies near the ACC, one carrying a memorable sign: “Put a Zipper on the Gipper.” But when the president entered the arena, the greeting was deafening.

In his introduction of the president, Hesburgh combined civic sensitivity and home-crowd levity. “We welcome the president of the United States back to health,” the priest began. “We welcome the president of the United States back into the body of his people, the Americans, and lastly, here at Notre Dame, here in a very special way, we welcome the Gipper at long last back to get his degree.”

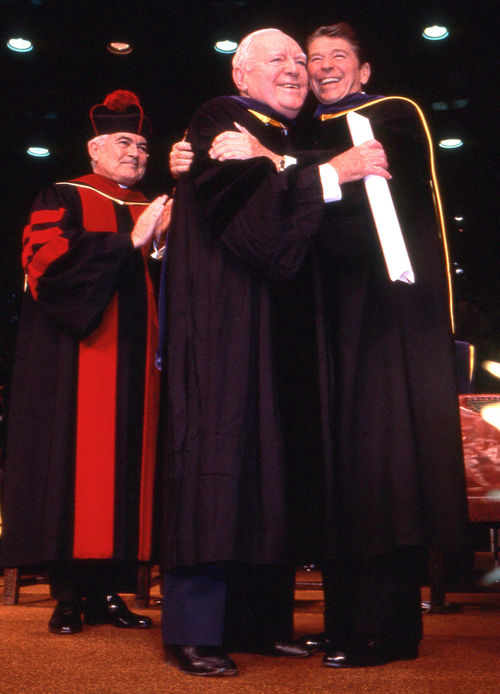

Before Reagan began to speak, he and O’Brien received their honorary degrees, bringing together the celluloid Gipp and Rockne in academic robes rather than football gear.

The president’s Commencement address was, in the judgment of veteran South Bend Tribune political writer Jack Colwell, “vintage Reagan.” The evils of “excessive government intervention” and the need to “transcend communism” were duly emphasized, as they tended to be in most every Reagan oration.

Yet what made this address distinctive was Reagan’s detailed disquisition about the importance to him of playing the Gipper and what Rockne, an immigrant from Norway, signified to American sports history. Reagan devoted 12 paragraphs of his half-hour talk to observations with Notre Dame relevance and resonance. At one point he admitted, “If I don’t watch myself, this could turn out to be less a commencement than a warm bath in nostalgic memories.”

Broadcast and print coverage of the president’s visit to Notre Dame was enormous. Many newspapers — including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune and Los Angeles Times — ran front-page stories and brightened their reports with photos of Reagan and O’Brien embracing on stage, beaming their joint delight.

The most eye-catching story on page one of The Washington Post the next day summed up the afternoon with the headline: “‘The Gipper’ Returns to Notre Dame.” The Chicago Tribune devoted an entire page of pictures to the presidential visit.

An incomparable, behind-the-scenes account of Commencement is Reagan’s own version, recorded as an entry in his White House diary, now available at his presidential library. “Father Hesburgh met us at the airport and we drove to Notre Dame,” his summary begins. “It was commencement for 2000 graduates but there must have been 15,000 all told in the auditorium. Pat O’Brien was there also to get an honorary degree. It really was exciting.

“Every N.D. student sees the Rockne film and so the greeting for Pat & me was overwhelming. Speech went O.K. and I was made an honorary member of the Monogram Club. When I opened my certificate I thought they’d made 2 copies — they hadn’t, the 2nd was to ‘The Gipper.’ He died before graduation so had never been made a member.

“Got back to the plane wringing wet — Cap & Gown plus an ‘iron’ vest makes for heat. Discovered a service I hadn’t been aware of — a change of clothing is always carried when I go on a trip. Change in this case meant a welcome dry shirt.”

Reagan left the stage shortly after he finished speaking, not staying for the remainder of the proceedings. Hesburgh only had a chance to offer the president a brief thank you while the audience applauded.

Back at his office in the Main Building that night, Hesburgh dictated a letter to Reagan that began: “I cannot thank you enough for your generosity and graciousness in coming all this distance, after your great crisis, to bring a good message to our graduating class of 1981.”

Later in his letter, Hesburgh brings up the mythology binding Reagan to Notre Dame: “The legend which you helped to create here, that of the Gipper, has been a living legend for every freshman who has ever come here to the University and seen the film which you helped to create. I hope that some day I might present to you an unexpurgated copy of this film which we recently found in our Archives. I think it might bring back many happy memories.”

True to his word, Hesburgh went to the White House in 1982 to give Reagan the restored film print. The president watched it in the company of Hesburgh and some well-known football figures. Reagan referred to watching the film in his diary as “quite an experience,” adding, “For me it was a truly nostalgic evening.”

Reagan’s delight in remembering, if not reliving one particular movie role took on new meaning during his presidency when political supporters encouraged undecided voters to “win one for the Gipper.”

Remarkably, nearly seven years after his 1981 visit, he returned to campus to dedicate a postage stamp honoring Rockne. For a president nearing the end of his time in the White House, it was yet another chance to renew a connection he never tired of making. “It was a wonderfully sentimental day,” he jotted in his diary.

A few days after Reagan accepted the invitation to speak at graduation four decades ago, Hesburgh concluded a note to the president outlining the agenda with these words: “Your presence will make Notre Dame’s Commencement an historic occasion.”

Indeed, it was.

Bob Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Professor Emeritus of American studies and journalism at Notre Dame. He is the author or editor of 15 books, most recently Fifty Years with Father Hesburgh: On and Off the Record and The Glory and the Burden: The American Presidency from FDR to Trump (both published by Notre Dame Press).