There are a lot of things that Ron Gregory ’61 finds puzzling.

He wonders why $175-a-pair gym shoes are marketed to kids in the projects who can afford them only by selling drugs.

He finds it hard to fathom how this country can successfully keep Cuban sugar and Cuban cigars from our shores but can’t find a way to keep out South American cocaine.

Equally puzzling is why most European countries ban fast-food chains from using trans fats in the grease they use for French fries, but this country doesn’t—despite national handwringing over child obesity.

And he can’t understand why a country that put men on the moon can’t find a way to keep kids in schoolrooms.

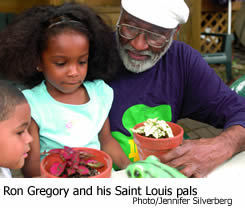

Most of the things that puzzle Gregory have to do with kids. The one-time cross-country runner who won multiple titles in high school and at Notre Dame has been a lifelong advocate for children—in Saint Louis school classrooms and gyms, in a neighborhood youth center, in summer camps for underprivileged children, and occasionally as a standup comedian—though he’s never achieved the fame of his older brother, comedian-activist Dick Gregory.

As a senior at Sumner High School in Saint Louis in 1956, Ron Gregory caught the eye of college track coaches when he set a national high school one-mile record. On a Notre Dame visit to watch the Irish beat North Carolina in the otherwise dismal 1956 football season (2-8), Gregory sat on the Irish bench between Paul Hornung ’57 and Aubrey Lewis ’58. He was enthralled by the excitement in the stadium and dazzled by the post-game celebrations. Back in Saint Louis he informed his high school coach, “I’m going to Notre Dame."

He was graduated from high school the following January and two days later was back at Notre Dame, a little disappointed to find the campus in winter hibernation and the celebrating over. But he stayed and began a string of achievements that included an indoor mile record of 4:10 that once ranked 9th in the ND record books, and All-America honors for a cross-country finish that helped the Irish win consecutive fourth place NCAA rankings in 1958 and ’59. While earning a bachelor of arts degree with a physical education major, he met a young South Bend woman named Joan Bath, who became his wife. The couple has a daughter, Tracie, and a granddaughter, Zoë, a 3-year-old with a million-dollar smile.

After ND, Gregory went home to Saint Louis to teach health and physical education at the elementary and high school levels. A part-time stint as a Job Corps street worker in low-income sections of the city a few years later convinced him his people skills and leadership ability made him better suited to work outside public education than inside. “Instead of kicking kids out of school, now I was helping them get back into school,” he says. He spent the next 13 years as director of neighborhood development programs under the auspices of the federal War on Poverty. Much of what he did in those years, he says, was fight waste and a timid bureaucracy that was afraid to try fresh approaches or rock the boat. Not so Ron Gregory: “My philosophy is, don’t hide from problems—deal with them.”

His next career move took him to the Youth and Family Center in Old North Saint Louis neighborhood, a one-time German settlement house that now serves a low-income, largely African-American section of the city. He joined the center as program director and moved up to associate director. Brenda Harvey Jones, who is now the center’s programs director, says Gregory’s impact on the lives of the adults and children served by the center was wide and deep: “He shares his life with everyone and is always a positive role model."

In 1998, feeling the tug of the classroom again after a 30-year hiatus, he worked out a part-time arrangement with the center and took a middle-school teaching position. Gregory says he went back to education because African-American males were so scarce in public education. “I had taken up a place in my Notre Dame classes, and I wanted to give something back,” he says. For the next five years he taught until mid-afternoon, then hurried back to the Youth and Family Center for the remainder of his working day, which was seldom governed by the clock.

A rude awakening

“I expected to find the same caliber students but got a rude awakening,” he says of his return to teaching. Things had changed in Saint Louis, as they had in most American cities. The school busing program, designed to fight segregation, had siphoned off “the cream of the crop,” he says. “A large percentage of the top students left the Saint Louis schools, and many of those who remained had hour-long bus rides each day.” Gregory is not a fan of busing. “If all that money had gone into the schools,” he declares, “it would have made a big difference."

Television had become another negative influence. “I asked a friend recently if he went to the movies every night of the week when he was growing up,” he says. “He said, of course not. But kids now watch TV all night—HBO, videos, cable movies—and they’re tired in school."

He had already learned from the Youth and Family Center’s summer camp program that children in the 8-to-12 age range tend to be sexually active today. Years ago the camp offered sessions open to both boys and girls, who slept in separate buildings. More recently the schedule had to be changed to single-sex sessions, because “the staff was staying up all night keeping the boys and girls from sneaking out to meet.” Society, he found, had changed profoundly.

How profoundly was illustrated when the school principal warned him not to take his classes out into the schoolyard because neighborhood kids would throw bottles into the yard, and bullets sometimes flew. “I took my classes outside anyway,” he says, “but I spent Monday mornings sweeping up glass from the yard, and when kids would pass by, I’d walk over to the fence and say ‘how ya doin?’ and I’d stay near the fence” to discourage arguments and confrontations.

Still trim and fit at 68, despite a back problem that dates to his college days and more recent shoulder injuries, Gregory is a vocal critic of the American diet, especially when it comes to what children eat. When he returned to teaching he was astonished by the soda and candy machines in school buildings. “There were none 30 years earlier,” he says. “Now I saw girls weighing 250 pounds and boys bulky enough to play football at Notre Dame. The school justified having these machines because the profits helped school programs. But drug dealers on the street use the same justification—the profits help their programs. Why put these bad habits in front of kids?"

Gregory attributes his habit of asking questions about things that make no sense to him to the four years of philosophy courses he took at Notre Dame. “Students then were required to take one course in religion, but I argued that a Baptist shouldn’t have to take a Catholic class.” The University gave in but insisted he’d have to take one philosophy course every semester. “I’m glad of that,” he says now, “because it exposed me to the concept of thinking. I learned in those courses the definition of change: the actualization of potential."

Much of his life was been devoted to thinking about how change can be accomplished. In the debate about whether it’s more effective to work from the inside or the outside, he leans toward the outside. “If you’re working inside, you’re bought,” he says. “So you have to work from the outside. But you need someone on the inside to feed you information, and that person will get fired and blacklisted. So there has to be an organization to support insiders after they’re nailed."

Gregory retired from the Youth Center last February. This past Memorial Day weekend a Saint Louis civic group sponsored a 50th year commemoration of his national high school one-mile record run. The day-long program featured a health and wellness seminar, reflecting his interest in alternative medicine and fitness. His brother Dick gave the dinner address to more than 200 people.

He sees friends from his Notre Dame days from time to time, and they still laugh about the meet with Michigan State when he was confined to the infirmary with pneumonia. Wearing a smuggled track uniform, he sneaked out of the infirmary, jogged over to the meet, and set a record for the half-mile before the sirens sounded and a frantic medical team showed up with an ambulance to haul him back to bed.

Walt Collins, a former editor of this magazine, teaches American studies at the University.