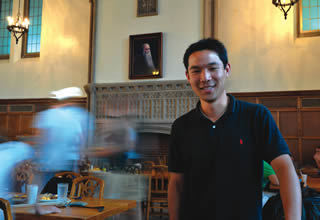

Growing up, Bryce Chung saw things going up and down the stairs of his home in Hawaii. He’d be at the piano and feel a presence, or play a computer game and catch the reflection of someone behind him in the monitor. It was unnerving, but once a neighbor intimated that she’d seen Chung’s deceased grandfather in the home, he relaxed. “Every time I saw something it was more like, ‘How’s it going, Grandpa,’” he says.

Now a fifth-year undergraduate in the chemical engineering/MBA program, Chung says a nastier experience during his senior year in high school left him anxious. “Something didn’t want me to be in my room,” he recalls. He struggled and managed to get out of bed.

“The interesting thing is, when I came to Notre Dame, I didn’t feel anything,” Chung continues. Not late at night along the walk between Fitzpatrick Hall and the Law School, not around the cemeteries. Nothing, that is, until he went to work at Reckers, the popular burgers-and-brick-oven-pizza eatery off the back patio of the South Dining Hall. The first time he restocked items in the basement that old feeling came back again. So he popped the question to his co-workers: “Has anyone ever seen ghosts down there?”

Several said they had. They told Chung about noises — hands clapping when no one was there and queer sounds they insisted aren’t pipes — and mysterious reflections back upstairs in the stainless steel of the dish machine. Reckers staffer Pam Bendit said that while she was washing dishes at 4 o’clock one morning she turned to see a white figure floating near the doors to the dining room. Only later when she saw the portrait of Father Sorin hanging above the fireplace in the west wing did she know who it was.

Chung the engineer sought explanations. Chung the storyteller wanted to share them. After consultation with the Student Activities Office and University Archives, he created a one-shot ND Ghost Tour that featured familiar tales about the ghost of George Gipp in Washington Hall and apparitions of Father Sorin in the Main Building. The tour drew 100 people to the LaFortune porch last Halloween. He laid out old reports of ghostly encounters in Washington Hall — mysterious voices and musical notes and the ascent of a ghostly horse and rider up the front steps — with various explanations. Tradition holds that the Gipper haunts the 1881 theater building where he lived at the time of his death, but Chung prefers the notion that the specter on horseback is the spirit of a Potawatomi Indian who long ago visited ancestors buried near the shores of the two campus lakes.

Meanwhile, Chung says, he had another encounter at South Dining Hall. As he finished work alone in the silent basement, he heard a radio in the pantry turn on. “I wasn’t going to stand around long enough to find out what that was,” he says.

And sure, he allows, it could have been a short circuit, or the volume surging in a radio left on, set to a station with a wavering signal. “I actually think [ghosts are] a manifestation of our brain,” he says, his engineering studies having immersed him in science, especially neurology. “At the same time, though, there are bits and pieces that are left unexplained by that approach. So I guess you could say I leave space for something greater.”

So, it turns out, does the Catholic Church, which has an extensive theology about the afterlife and a remarkable tradition of the unseen world — heaven and hell, angels, demons, saints and souls — but has never made definitive institutional pronouncements, yea or nay, about the possibility of ghost encounters or hauntings. Yet the prolific Boston College philosopher and popular religious author Peter Kreeft writes, “Nevertheless, without our action or invitation, the dead often do appear to the living. There is enormous evidence of ‘ghosts’ in all cultures.”

In Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Heaven, Kreeft distinguishes three kinds of ghosts: “Sad” and “wispy” souls working out “unfinished earthly business”; “malicious and deceptive spirits” who “probably come from Hell,” even the possibility of which should “terrify away all temptations to necromancy”; and finally the “bright, happy spirits of dead friends and family” who come “at God’s will . . . with messages of hope and love.”

Maybe that explains the Washington Hall appearances of another ghost, possibly Brother Canute Lardner, who died during a movie there one afternoon in 1946. Father Robert Austgen, CSC, ’55, an avid collector of campus ghost stories, says custodians have reported encounters with an elderly man, “Irish, balding, with reddish hair.” One found him gazing out a window on the east side of the building’s first floor. “Could you open the window please?” he asked with a brogue. The marveled custodian said, “I don’t think I know you.” And the man replied, “Oh, it’s quite all right. I’m with the building.”

Austgen keeps a 33-page binder filled with such tales. Some suggest that Father Sorin, who died on Halloween in 1893, walks the campus just to keep an eye on the place. When University administrators temporarily relocated to Hayes-Healy Hall during the Main Building renovation a decade ago, night cleaners reported “an elderly priest in habit, with long beard, roaming the corridors.” They thought little of it until one noticed the priest had no feet and others saw him pass through walls.

At Saint Liam Hall, the recently renamed Student Health Center, stories circulate of kindly nuns making rounds after hours. And during Christmas breaks security guards have responded to mysterious 911 calls reportedly placed from phones in the empty building.

So are there ghosts at Notre Dame, or anywhere for that matter? “Nah,” says ND psychology Professor George Howard. “No more than there are spaceships that take people away.” Literally millions of people around the world have claimed to be abducted by aliens in UFOs, says Howard, the co-author of a book on the subject.

For Howard, abduction narratives and ghost stories fall within the spectrum of an essentially normal psychological condition he calls “fantasy prone,” the ability “to let yourself get sucked into a partially realistic but also partially fanciful story.” Howard says this can get dangerous for storytellers who insist too loudly and too often on their experience and risk being labeled psychotic.

On the other hand, he adds, anyone who argues that ghosts aren’t real and that therefore believers are lunatics, “doesn’t understand that we’re all lunatics to a certain extent. It’s just that I tend to work my lunacy through fantasy football.”

Bryce Chung dwells in the tension between such explanations and acceptance of the supernatural. The erstwhile guide of Notre Dame’s ghost tour likes the “awe factor” but still wants answers. “I’m not telling you what’s true or not,” he concludes with a chuckle. “Have fun with it.”

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.

Photo of Bryce Chung by Matt Cashore.