Editor's Note: This piece is part of "12 Days of Classics," a holiday series drawn from the magazine's archives and published at magazine.nd.edu from Saturday, December 22, 2018, to Wednesday, January 2, 2019. Merry Christmas!

At this time in the Christian year, we are often reminded that the Gospel of Matthew records a peculiar astronomical event that occurred at the birth of Christ. As a child, I had a vivid image of what this event must have looked like.

On December 24, 1 A.D., a special star appeared above a stable in Bethlehem to point the way for three kings from the Orient so they could meet up with some humble shepherds to witness a special child who had been born in this humble place. I assumed that everyone understood that this star of Christmas must have had some sort of special pointing ray to show where the baby was wrapped in swaddling clothes.

Now, years later, I study stars for a living. That is, I work as a theoretical astrophysicist at Notre Dame. When my kids ask me what I do for a living I say, “Colleagues come to me and say, ‘I saw a star do such and such, what is it?’” I run computer models to try to explain what they saw.

We have a lot to say about the stars these days. We know that our sun is but one star in the collection of a hundred million stars that make up the galaxy, and that our galaxy is but one of a billion others. That means that there are something like a hundred million billion stars out there.

So we ask: Of the hundred million billion stars out there shining down from the heavens, which is the one that made its appearance known on that special day so long ago?

For many years, astronomers, historians and theologians have pondered the question of what this “Christmas star” could be. Many possibilities have been suggested. Let’s take a look at how modern astrophysics weighs in on this question. If a colleague asked me what something was in the heavens I would ask three questions: When did it occur, how long did it endure, and what were its characteristics?

Let’s look at what we can discern by these same three questions of the Christmas star.

When did the Star appear?

The Gospels of Matthew and Luke give us some insight on this. Here is what is said:

“Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem saying, “Where is he who has been born king of the Jews? For we have seen his star in the East and have come to worship him.” (Matthew 2:1)

The first hint is that it was in the days of Herod the King, which means before the end of the days when Herod was king. There is both a historical and biblical record of when the reign of Herod ended. The Roman historian Flavius Josephus in Antiquities of the Jews recorded that Herod died after an eclipse of the moon and was buried before the Passover.

Here is where astrophysics can say something. We know how to calculate the dates of lunar eclipses to high accuracy. And the Passover date each year is fixed by the date of the full moon relative to the first day of spring (vernal equinox). This would place it at one of several dates. These days the software to calculate eclipse dates even in antiquity is readily accessible. The partial eclipse on the night of March 12-13 in 6 B.C. is the one favored by most historians, as it correlates well with the accounts of the reigns of Herod’s three sons, also recorded by Josephus. Although some have suggested that eclipses in 5 B.C., 1 B.C. or 1 A.D. are also possibilities.

There is also corroborating evidence for the 6 B.C. date from Luke 3:1, which records that John the Baptist began preaching in the 15th year of the reign of Emperor Tiberius and that Jesus (who is six months younger than John) began his ministry at an age of about 30. If “about 30” means more than 27 and less than 33 years old, then this would mean the birth of Jesus would have occurred after 8 B.C. and before 2 B.C. The answer to when the star appeared would then seem to be somewhere in the range of 8-4 B.C. although dates up to 1 B.C. remain a possibility.

There is more to the story, however. Later in the Matthew account we read:

“Then Herod summoned the Wise men secretly and ascertained from them what time the star appeared.” (Matthew 2:7)

“Then Herod when he saw that he had been tricked by the wise men was in a furious rage, and he sent and killed all the male children in Bethlehem who were two years old or under according to the time which he had ascertained from the wise men.” (Matthew 2:16)

This tells us that the star may have occurred up to two years before their arrival in Jerusalem, which would be as early as 10-3 B.C. for the star’s initial appearance.

Characteristics of the Star

The second question is: what did the star look like?

First we read: “We have seen his star in the East.” (Matthew 2:7)

Here, in the East is the Greek “en te anatole,” which literally translates to “as it rose.” This suggests that the star appears near sunrise.

Next we read: “When they had heard the king they went their way; and lo, the star which they had seen in the East went before them, till it came to rest over the place where the child was. When they saw the star they rejoiced exceedingly with great joy.” (Matthew 2:9-10)

This offers useful insight. It says that the star, which they had seen, previously must have reappeared in some form and seemed to rest in the sky. This tells us something about the duration of this astronomical event. It must have endured for at least the travel time from their point of origin to the end of their trip to Bethlehem.

To estimate the time scale we need to know how far the Magi had to travel and their average speed. It is likely that the Magi were from Babylonia or Mesopotamia, making it about a 500-mile journey. Caravans in those days were pressed to make 50 miles a day, which would make a minimum duration for this event of about 10 days. It would probably be longer, however, because the caravan would probably be slower and one must allow for prep time and the duration of the visit in Jerusalem.

Based upon the dates in the account of the slaughter of the innocents, that would place the time frame of this event to be between 10 days and two years. The fact that the star reappeared could mean that it was a recurring phenomenon or that it went behind the sun and emerged later on the other side, or that some new event also appeared in association with the first appearing with the sunrise.

Candidates

In astrophysics, once we have identified when an event occurred and the time frame over which it occurs, we can start to identify candidates that would match that event. So if a colleague said to me, “We saw an event that was visible to the naked eye. It lasted or reappeared over an interval of somewhere between 10 days to two years and seemed to rest in the sky,” several candidates would immediately come to mind.

I would say it must have been a comet, a nova, a supernova or an alignment of the planets. The next question one should ask is “Did anyone else see it?”

Let’s look at each of these possibilities and see if there is astrophysical or historical evidence that they could have been the Christmas star.

Comets

Comets, often depicted in nativity scenes, seem like a natural candidate. Comets are mostly objects in highly elliptical orbits, occasionally coming close to the sun. They contain an icy nucleus, which evaporates and gets blown into space by solar wind pressure. They can be spectacular events. They appear suddenly when a comet is near the sun and are visible for months as they traverse the sky. They could indeed appear and reappear if the comet were on an orbit, which travels behind the sun

A properly oriented comet with a tail might appear to point or rest over a place. See, for instance, comet Hale-Bopp appearing to “rest” over Mono Lake, California, during its passage in 1996.

Of course we must ask if anyone else happened to notice that a spectacular comet was around during the critical time frame of 8-4 B.C. Fortunately, Chinese astronomers maintained careful dates for comets and other celestial events, which have been preserved to this very day.

Three comets were noted between 20 B.C. and 10 A.D. One of them is recognized to have been Haley’s comet in 12 B.C. The other two (a comet with tail in the constellation Capricorn in 5 B.C. and a comet with no tail in the constellation Aquila, perhaps a nova or supernova, in 4 B.C.) both fall in the desired time frame.

The one in 5 B.C. is an intriguing possibility and has been suggested as the Christmas star (Humphreys 1991). The one in 4 B.C. is also an interesting possibility. Since neither of these comets has been identified with a known object, then it must have an orbit period of greater than about 2,000 years.

If we apply Kepler’s 2nd laws of planetary motion, which says that the orbits of planets or comets sweeps out equal area in equal time, then the comet must currently reside something like 10,000 times the Earth-sun distance, or about 250 times farther than the orbit of Pluto. This would place the comet in something called “the Oort cloud,” which is known to contain trillions of comets.

There is a problem with a comet as the Christmas star, however. In ancient times comets were thought to be harbingers of disaster and often believed to signal demise of a king rather than the welcome of a new king. They could, however, represent a change of the current regime. Among other great disasters in Roman history, the deaths of Cleopatra in 30 B.C., Marcus Agrippa in 12 B.C. and Augustus Caesar in 14 A.D. were all associated with the appearance of a comet. Hence, it is difficult to imagine how the Magi rejoiced at the reappearance of the star unless they were elated at the pending demise of Herod.

Novae

Novae are relatively frequent appearances of a “guest star.” They turn on and off over a period of years. Novae occur in binary star systems in which one star is a normal star while the other is a compact white-dwarf. Such stars are the remnant of the death of a star like the sun, in which about half of the mass of the sun has been compressed to a millionth the volume of the sun, making a dense object which is about the size of the Earth. Hydrogen-rich gas pours from the normal star into an accretion disk around the white dwarf and then builds up a shell of material on the surface of the white dwarf.

However, as this material accumulates, it becomes hotter and denser. Eventually it ignites into a thermonuclear explosion, which causes the star to light up for days or weeks as material is ejected from the star.

An object seen in the constellation Aquila by Chinese astronomers in 4 B.C., which they called a comet, could have been a nova. A number of recurrent novae have been identified in Aquila, and one could have been the Christmas star.

My favorite candidate is the object Nova Aquilae V603. When this nova erupted in 1918 it was the brightest star in the sky. It is completely possible that the faint “tailless comet” event recorded by Chinese astronomers in 4 B.C. could have been this object. Particularly since there is no note that it traveled across the sky as comets do. Hence, it is possible that this was the Christmas star. The problem with novae, like comets, however, is that they were not considered to be signs of good things to come. Like comets, they were thought to denote disaster.

Supernovae

Supernovae seem like a natural candidate for the Christmas star. They are millions of times intrinsically brighter than novae and correspond to the most spectacular events in the cosmos since the big bang itself. In a supernova, a single star becomes as bright as all of the 10 billion stars of a galaxy.

Supernovae occur in two different types, which are classified according to whether atomic lines of hydrogen can be seen in their light spectrum. If there is no hydrogen it is a type I supernova. If there is hydrogen it is classified as type II. There are also subcategories, but the most common of the no-hydrogen variety, Type IA supernovae, are believed to occur whenever a white dwarf star accretes enough mass from a companion normal star to nearly collapse under its own weight. A thermonuclear explosion is triggered within the interior of the star once the density is high enough. This explosion engulfs the entire star. The most common of the variety with hydrogen lines is believed to result from the collapse of the core of a star with at least 10 times the mass of the sun.

The collapse of the star forms a neutron star, and an outgoing shock wave, which becomes heated as neutrinos emitted from the neutron star generate a high-pressure bubble that lifts off the star. Although each type of supernova arises from quite different scenarios, it turns out that they both become bright for about the same amount of time. They typically achieve maximum brightness for a number of days and then slowly dim over months.

On almost any given night. a search with modern telescopes will reveal a supernova in an external galaxy somewhere. These are all much too faint to ever have been seen by ancient observers. Occasionally, however, a supernova occurs in our own galaxy, and they can be very bright indeed. Some have been nearly as bright as the full moon.

Did a visible supernova occur at the critical time, around 4-8 B.C.? We have two ways to possibly answer that question. One is the recording of “guest star” supernovae by ancient astronomers. My check of "guest stars” supernovae recorded by Chinese astronomers in the interval from 1600 B.C. to 2000 A.D. revealed that none were noted by the ancient astronomers during the crucial interval.

The other means we have to search for possible supernova Christmas-star candidates is the identification of the remnant of the explosion. After a supernova explodes, a shell of material is ejected from the star. Supernova remnants are identified by the high-temperature fast-moving shells from the explosion. One can determine ages for supernova remnants by dividing the distance that the material has reached by the speed of the expanding shell. This age estimate is rather uncertain, but of the more than 500 known supernova remnants in the sky, there are only two with ages of about 2,000 years (Seward and Wang 1988).

Those two remnants are known as Kes 75 and RCW 103. Could either of these have been visible to the Magi? Possibly. The object Kes 75 is near Altair in Aquila, so it is a candidate for the guest star of 4 B.C. It is 60,000 light years away. This is so far away in the galaxy that it may not have been particularly spectacular (Seward and Wang, 1988). This is consistent with the fact that the guest star of 4 B.C. was dim. The object RCW 103, on the other hand, would have occurred in the triangulum constellation, which is on or just below the horizon from Jerusalem and may have been difficult to see.

Planetary alignments

A planetary alignment is the last candidate. Although it is not as spectacular as the other candidates, it is the one that most theologians and astronomers have identified as the Christmas star. To see why this makes sense we must ask who were the “wise men from the East”? And how could they have determined that this peculiar event pointed toward a regal birth in Judea, when this event was apparently missed by all but a few shepherds in the field?

The word “Magi” comes from the Greek root word magos, which refers to Zoroastrian priests. They were astrologers. They were in demand at the time as consultants to rulers. The main centers of this system were in Babylonia or Mesopotamia, which is probably where they were from. By the time frame of 4-8 B.C. they would have practiced a Hellenistic (Greek) astrology after the system was unified following the conquests of Alexander the Great hundreds of years before.

Interestingly, they had their own belief in a coming messiah, but their beliefs reflected a sense of determinism, which in their view was connected with the motions of the sun, moon and planets in the sky. In their belief system, each constellation of the zodiac was assigned to a different geographic region of influence. The location of the sun, moon or planets in a constellation spoke of the character of a person born on that day.

The strongest such statement would occur when more than one planet plus the sun or moon were to occur in the same constellation at the same time. There is evidence from the writings of the famous astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, and also from the minting of Roman coins at the time, that Aries was the constellation thought to be associated with the region of Judea. This was particularly significant as Aries was also the constellation containing the vernal equinox at that time. An event that occurred in Aries would imply the redemption and new life associated with the coming of spring.

Several planetary alignments have been proposed as the Christmas star — and two most significant planetary alignments occurred in the relevant time frame of 4-8 B.C. These are popular candidates as the Christmas star. One occurred on Feb. 20, 6 BC. It involved an alignment of Mars, Jupiter, Saturn in the constellation Pisces. The other occurred on April 17, 6 B.C. In this amazing alignment, the sun, Jupiter, the moon and Saturn were all in Aries, while Venus was next door in Pisces, and Mercury and Mars was on the other side in Taurus. It is also popular to consider the close alignment of Jupiter and Venus in Leo on June 17, 2 B.C.

A great deal can be said about the significance of April 17, 6 B.C. alignment (Molnar 1999). A few highlights are the following:

1) The sun, Jupiter, moon and Saturn are in Aries; Venus in Pisces; Mars is Taurus. This alignment of five planets and the sun and moon is very rare;

2) Recent evidence based upon a coin minted in Antioch to commemorate this alignment suggests that the sun in Aries meant this alignment would be particularly significant for a person born in Judea;

3) Jupiter and the moon in the same sign meant a powerful leader would be born who would die at an appointed time;

4) Saturn together makes the ruler “most powerful”;

5) Other “attending” planets Venus and Mars support the significance of this leader;

6) Jupiter was moving backward relative to the background sky and indeed would have stood in the east in Aries;

7) On the day after, Jupiter left Aries and became visible before sunrise, implying that this “star” would have literally been seen in the east.

This would seem to explain a lot of things about the Christmas story. The Magi would have seen this in the east and recognized that it symbolized a regal birth in Judea. Surely, such an event would have appeared significant enough to inspire the Magi to inquire about this ruler. At the same time, astrology was an abomination to the people of Judea, which perhaps explains why no one in Herod’s court was apparently aware of this event.

As to how the star goes before the Magi on their journey toward Bethlehem, and stood over where the child lay, this too has an astrological meaning. In the Greek, “going before” can be an astrological term that refers to a planet moving backward on the sky. Usually planets appear to move from west to east relative to the background stars.

However, the outer planets appear to change to a westward motion. This phenomenon is known as “retrograde’ motion in modern astronomy and arises as the earth overtakes the outer planets as it moves on its orbit around the sun. The term “stood over” was also used in ancient astrology to denote the apparent standing still of a planet compared to background stars as it reverses its motion from westward to eastward. Jupiter would have “stood over” about six months after the planetary alignment.

A shining conclusion

So now, years later from my childhood, I realize that the Christmas star in the Christmas story may have unfolded quite differently than I had imagined in my youth.

After weighing all of the astrophysical and historical evidence it is difficult to say for sure exactly what was the Christmas star. My own opinion after looking at this is that the planetary alignment hypothesis is the most compelling and would fix the date of the birth of the Christ child to April 17, 6 B.C., with the visit of the Magi some six months later. At the same time, however, the Capricorn comet in 5 B.C. or the Aquila nova or supernova in 4 B.C. remain to me as intriguing possibilities for an event that might have occurred when the Magi arrived in Bethlehem.

No matter what the Christmas star was or when it appeared, the last question we should ask is why the Son of God would make his appearance known to distant astrologers rather than the faithful in Judea. Especially since astrology was forbidden in Judea.

In answer to that I would suggest that God would have known that these creatures He created would look to the sky to try to understand and interpret our place and destiny in the cosmos. As a modern astrophysicist, I feel a kindred connection to these ancient Magi, who were earnestly scanning the heavens for insight into the truth about the nature and evolution of their universe, just as we do today. I am moved that the Son of God chose to reward those who seek the truth with a heavenly sign of His appearance.

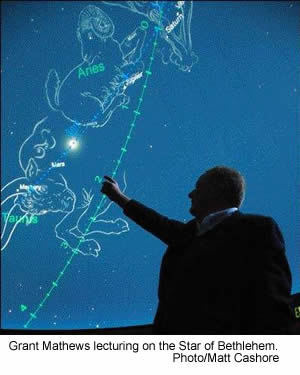

Professor Grant Mathews is director of Notre Dame’s Center for Astrophysics.