When as an adjunct professor of English in Texas, I taught (or perhaps more accurately exposed) the skill of essay writing to college freshmen, I customarily would assign as my students’ first research project the Authorship Question.

In the last several centuries considerable argument has raged around the career of William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon — a person who beyond doubt did exist. The controversy is over whether the Shakespeare we know and love did in fact write those plays and sonnets that have earned him fame as the greatest poet in any language.

Most inexplicably, and certainly unlike others who have earned their reputations as authors, he left us not one scrap of writing — no manuscripts, no first drafts, no notes, no letters, not so much as a grocery list — nothing but a half-dozen or so signatures, none of which spell his name as we spell it, and all of which, according to the doubtful, appear scrawled by someone clearly unaccustomed to holding, much less using, a pen. The question of Who Wrote Shakespeare further obscures the hunt for the so-called Dark Lady of the Sonnets, a famous unknown rather like Beethoven’s mysterious Immortal Beloved.

I told my students to do the research and settle in their own minds the identity of the author we know as Shakespeare, then write an essay to convince me.

One morning at the end of class, after delivering my opening lecture on this subject, naming a dozen or so likely and unlikely names of the “real” Shakespeare poets — ranging from the Earl of Oxford to Christopher Marlowe to Francis to Queen Elizabeth herself — and after handing out to the students copies of Diana Price’s fine article summing up the problem in Skeptic magazine, as well as suggesting some good Internet search phrases, I looked up from my notes to face an obviously troubled young lady, a high-school graduate and a product of the Houston Independent School District, an organization not celebrated for its academic excellence.

“Who,” she asked, “was this Sha… Sha… did you say Shakes… Shakespeare? Who is that?”

Good question, lady. The very question, in fact, that I just assigned to you.

This brought to my mind, not for the first time, an even more intriguing question: why Dame Fortuna, the ancient Roman deity in charge of bestowing luck and fortune for good or ill, and worshipped by the Greeks as the goddess Tyche, not only lays her fickle finger betimes on the undeserving, but so often maddeningly withholds her magic touch from the deserving until after they die.

We have lost even the names of some quite famous persons. Despite the outrageous claim uttered by one of the Beatles, nobody knows for sure the actual proper name of the man who probably is the most famous personage in history, but his friends and family certainly never called him Jesus Christ. More likely they knew him as something like Yeshua bin Yusef — in English, Joshua Josephson — but his name became “Greekized” because the Evangelists likely wrote their gospels in Greek.

Like William Shakespeare, Jesus left us nothing at all in his own writing, and for that matter neither did Socrates, despite the many famous quotes attributed to all three. Of the reputedly superb literary genius of the Greek poet Sappho we have next to nothing — only a scrap or so quoted in the works of other writers. As for the Etruscans, whose civilization and splendid art preceded those of ancient Rome, we possess not even their language, much less their literature.

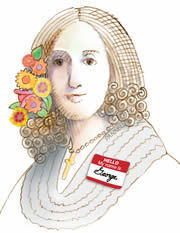

Many celebrated authors live on not under their real names but in pseudonyms. Even folks well versed in literature sometimes have to think for a moment before dredging up from memory the true names of O. Henry, Mark Twain, George Eliot or George Sand. Who knows, we might not even have the name of Jane Austen, one of the greatest authors in the English language and a staple of present-day movies and Masterpiece Theatre, had her novels continued in publication as they first appeared, “by a lady.”

The Dark Lady of the Sonnets and the Immortal Beloved have plenty of company among thousands of unnamed souls who have achieved immortal fame through, so to speak, the back door. Think of the two “thieves” crucified along with Jesus, of King Herod’s “Slaughter of the Innocents,” of all those people buried in Thomas Gray’s country churchyard or who met untimely deaths in a cruel sea after the sinking of the Titanic and the Lusitania.

It would certainly have surprised — even dismayed — Emily Dickinson to have learned that after her death she would become celebrated as one of the greatest poets in American literature. On the other hand, it would have miffed Franz Schubert and Vincent van Gogh and Franz Kafka, who surely had some aspirations to recognition, hopes based on a personal and quite accurate appreciation of their own artistic genius, to find that they would die having completely missed out on worldwide fame, not to mention posthumous millions in income.

Then let us consider Felicia Hemans, a celebrity poet in English during Jane Austen’s heyday, who must have confidently expected her fame to survive the grave. Ever hear of Mrs. Hemans? Anybody? And how many vice presidents of the United States can you name, offhand?

I’ve heard it asserted that history would now call Adolf Hitler one of Germany’s most admirable leaders, had he happened to die before Kristallnacht. But Dame Fortuna sometimes enjoys making her famed favorites infamous. Joan Crawford died a great motion picture star before she became Mommie Dearest.

Fortuna also gets a laugh out of untwisting her cruel twists. Oscar Wilde, the toast of the London stage, got toasted himself when his public and the long arm of the law learned of “the love that dares not speak its name.” Wilde made the mistake of suing for defamation of character, an ill-considered act that only draws public attention to the fact. The author Lillian Hellman lived to commit the same error when she sued her longtime foe Mary McCarthy for having publicly, and not without justification, called every word written by Hellman a lie, including “and” and “the.” We have once again raised Wilde to glory as a wit and playwright, although of course Oscar himself didn’t live to enjoy it.

Everybody considered Czar Nicholas II and Kaiser Wilhelm II as hopeless incompetents well before their deranged imperial power led to the senseless slaughter of millions of Europe’s young men in the Great War. And even Fortuna’s magic touch can never restore to them a redemption they never earned in life.

She more often can, however, cause many of her most cruelly fated victims to come out smelling like the proverbial rose. Friends, family and acquaintances viciously rejected Mary Ann Evans for her scandalous lifestyle before she became England’s most acclaimed author and one of the nation’s wealthiest women, admired and sought after under her nom de plume George Eliot. People and politicos alike rose up in outrage against “Mad” King Ludwig II of Bavaria, adjudging him insane, deposing and condemning him for building extravagantly expensive fairyland castles — castles that now, long after his death, flood Bavaria with millions of Euros from awestruck tourists.

To Jean-Jacques Rousseau we owe the essential beginnings of our society’s care for the nurturing, upbringing and education of children. All the world has sung his praises, including such notables as Kant, Shelley, Schiller, John Stuart Mill, George Eliot, Hugo, Flaubert and Tolstoy. Yet Rousseau’s own five illegitimate children he dropped off to the depredations of the terrible orphanages of his time. We quite rightly know Percy Bysshe Shelley as one of the greatest poets in English, but according to Paul Johnson’s wonderful book Intellectuals, Shelley also had a personal career as an unfeeling monster who destroyed the lives of everyone he touched.

Obviously, some well-known names live on in well-deserved infamy: Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Lucrezia Borgia, Ivan the Terrible, Oliver Cromwell, the debauched young third-century Roman emperor Elagabalus. Others deserve all the praise fame can bestow: Mother Teresa, the Dalai Lama, Black Elk, Madame Curie, Pope John XXIII.

History sometimes bestows its plaudits on men who deserve its shame instead: the “heroes” of Goliad, the Alamo and San Jacinto, who gave their lives in defense of slavery. Many have reputations that may deserve approbation or disgrace, depending on whom you read: Henry VIII, “Bloody” Mary, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Pope Pius XII, Julius Caesar. Some may just possibly, even if improbably, have “taken the rap” for others guilty but unknown. Lee Harvey Oswald comes to mind. And did Lizzie Borden really take that ax and give her mother 40 whacks?

Some, like the Greek poet Homer, to whom we attribute the Iliad and the Odyssey, or the Roman hero Aeneas, celebrated in Virgil’s Aeneid, may or may not have actually walked this earth. Some people who did, oddly enough, have taken on fame only as fictional characters: Scotland did indeed have a King Macbeth, and who would ever have thought twice about the real Saint Nicholas, had he not become Santa Claus? The Vatican itself has cast doubt on the historicity of Saint Patrick, and as for the Irish belief that he drove out all the snakes, well . . .

Some fictional characters, like Harry Potter and Sherlock Holmes, have greater fame than almost any real people, but their only slightly less well-known authors collected the money. At least one famous fictional character, the resurrected creation given life by Dr. Frankenstein in the novel by Mary Shelley — who portrayed him as pretty ugly all right, but really a sweet, pitiable, even lovable creature nonetheless — took on the name of his fictional mad-scientist creator when Hollywood and Boris Karloff remade him into an infamous and fearsome horror.

Does William Shakespeare really deserve his reputation as the greatest poet in any language? The Russians, as usual, don’t agree, bestowing the palm instead on their own Alexander Pushkin. The great-grandson of a black page in the court of Peter the Great, Pushkin has inexplicably escaped the notice of the promoters of Black History Month.

So exactly who did write those plays by “Shakespeare”? Personally, and for several rather lame reasons, I side with the decided minority that point to Queen Elizabeth. But genius has its reasons that reason cannot know. And the Stratfordians — the scholars firmly and solidly in Shakespeare’s camp — have countered with excellent arguments against all the alternative candidates. My son Michael came up with my own favorite among the objections demolishing the claims for Christopher Marlowe as the Shakespeare Poet: “He would need to have gotten a lot better.”

Does it really matter? Fortuna’s touch should have made John Maynard Keynes a household name for his enormous influence on the economic policies of the United States and the world, instead of making him well-known only to academia and the readership of John Kenneth Galbraith. But Keynes had the last word: “In the long run we are all dead.”

Patrick Dunne lives and writes in Houston, Texas. After a career teaching literature and writing, he entered law school at age 53 and practiced immigration law until his retirement in 1999.