The hardcourt wizardry of forward Tim Abromaitis and guard Ben Hansbrough on the men’s squad and superstar guard Skylar Diggins on the women’s team stoked national championship chatter among Irish basketball fans a year ago, but many remain unaware that such excitement had occurred before. In mentioning past Notre Dame championship teams, one inevitably thinks of George Gipp, the Four Horsemen and other gridiron heroes. Back in the 1930s, though, Notre Dame dominated college basketball much the way Knute Rockne’s teams had barreled through the football landscape.

Coached by George Keogan and propelled by what one publication called “the immortal trio of Notre Dame basketball,” in 1936 the team captured Notre Dame’s last undisputed men’s national championship, playing a brand of basketball one New York Times sports reporter called “as near perfection as it could be.”

Keogan was no stranger to winning. He had one national title under his belt, and his 327 career coaching wins place him second today only to Digger Phelps at 393. After an uneven 1934-35 season in which his Irish squad posted a 13-9 record, he pinned his hopes on a few established veterans and a promising crop of untested sophomores.

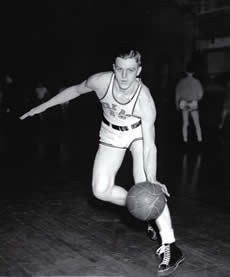

The team opened with seven straight victories, mostly against lighter opponents such as St. Joseph’s College. In a sign of what was to come, sophomore scoring machine Johnny Moir took a pass from 6-foot-6 sophomore center Paul Nowak to notch the season’s first basket, against Albion, while substitute forward Ray Meyer and guard Tom Wukovits, both sophomores, combined laser passing with unyielding defense in support of seniors George Ireland, John Ford, Johnny Hopkins and Frank Wade.

They stumbled in their first big test, falling 54-40 to a speedy Purdue bunch that had been the Big Ten co-champion the year before, then followed with an unusual contest against Northwestern. After both squads had left the floor in an apparent 20-19 Northwestern victory, official scorers detected an error and declared a 20-20 tie. Since the players were already showering and much of the crowd had left, both schools agreed to accept the result, and the only tie game in Notre Dame basketball history went into the books.

Coach Keogan’s patience wore thin four days later when his team tallied a mere six points in the first half against Minnesota. Hoping to put a spark in his offense, Keogan turned to his talented sophomores, including Nowak, Moir, Tommy Jordan and Wukovits, who scored every point in a second half comeback to win, 29-27.

With an 8-1-1 record, the team began its “suicide schedule.” Over the next 10 games they would square off against eight reigning conference champions.

They began their run with a 43-35 win over Pittsburgh on January 10 and rolled past Marquette a few days later. “The game featured the playing of Notre Dame’s flashy crop of sophomores who dominated the scene from start to finish,” Scholastic magazine said of that performance.

After polishing off Pennsylvania, 37-27, the Irish headed to Syracuse for a game against a rival that had not lost on its home court in four years. Despite yielding a height advantage to Syracuse, who fielded five men over 6 feet tall, the Irish defense checked high-scoring center Ed Sonderman to swipe a 46-43 win.

The Irish now faced their harshest tests with consecutive matches against the top two teams in the country, legendary coach Adolph Rupp’s vaunted Kentucky Wildcats and New York University — the only team to which Kentucky had lost. Moir netted 17 and Nowak 11 to lead the Irish to a 41-20 victory, the most lopsided defeat of Rupp’s first six years at Kentucky.

Four days later, the Irish arrived at Madison Square Garden to take on powerhouse NYU. The game sold out three weeks before the match, and Scholastic magazine urged campus readers who wanted to listen to a radio broadcast to deluge CBS with letters asking for a transmission to the Midwest.

New York returned every starter from the team that had defeated Notre Dame the year before. Confident the local five could handle the Midwesterners, one New York Times reporter hoped that Notre Dame would at least put up a decent fight so the game did not bore fans.

The writer failed to account for both the Irish talent and Notre Dame’s national allure. More than 19,000 spectators jammed the Garden, at that time the largest crowd to watch a basketball game in New York. Keogan later admitted, “It was a sight to behold, and one that would make the blood of any coach fairly tingle.”

The outcome was never in doubt. After spotting NYU three points, Notre Dame raced to a 25-13 halftime lead. George Ireland shut down NYU’s high-scoring forwards and tallied seven points on the night. Filling in after the half for star Johnny Moir, who had gotten into foul trouble, Johnny Hopkins added another 10 as Notre Dame handed NYU a 38-27 defeat. It was the school’s first ever loss in Madison Square Garden, convincing even the infamously partisan New York sportswriters that “the finest basketball is not played in New York.” Most conceded that Notre Dame was the No. 1 team “from coast to coast” and some even urged their selection to represent the country in the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games.

Despite having garnered in 1927 his first Helms Foundation National Championship, the honor accorded the premier team in the land in the days before post-season tournaments, Keogan called his 1935-36 team the best in Notre Dame history because it had dominated a schedule no other squad could match. The team scored so speedily that they were the first to be called a “point-a-minute” squad. They set records in games won, total team points in one season, average points per game, and points in a single game — 71 against St. Joseph’s — in compiling a 22-2-1 overall record.

Moir, who established an individual season scoring record with 260 points, was named the nation’s outstanding college player by the Helms Foundation. He and Nowak were named consensus All-Americans. And while the Helms Foundation awarded the Irish their second national championship in nine years, University policy against post-season play eliminated any hope of participating in the Berlin Olympics.

Built upon the exploits of “the immortal trio” of Nowak, Moir and Wukovits, Keogan’s squads followed their 1936 run with back-to-back 20-3 records. Behind Moir’s scoring, Nowak’s rebounding and the passing and defense of Wukovits — nicknamed the “guarding angel” — in both years they convinced many sportswriters that they again deserved championship recognition. When they needed a breather, second-string forwards Ed Sadowski and Mike Crowe carried the load, but a follow-up national title proved elusive.

On March 4, 1938, the big three played their final home game before 5,500 fans. In defeating Marquette, Nowak scored 15 points, Moir 11 and Wukovits 7, earning a tremendous ovation at game’s end that recognized three years of stellar basketball and a 62-8-1 record.

After the game Scholastic writer John F. Clifford ’38 credited “the fastest breaking, deadliest shooting and sharpest passing trio in the game today” for producing “Notre Dame’s Golden Era of Basketball,” and equated their impact to that of the Four Horsemen.

Their basketball days did not end with graduation. Moir, Nowak and Wukovits became the first Notre Dame alumni to play professional ball, continuing their winning ways together for the Akron Firestones in the National Basketball League.

Two of their championship teammates made names for themselves as college coaches. George Ireland’s Loyola University of Chicago teams won 321 games over 24 seasons. In 1963 he led the school to a national title in a 60-58 overtime thriller against Cincinnati.

Meanwhile, Ray Meyer was building crosstown rival DePaul into a national power. Winning 724 games over a 42-year career, Meyer led his teams to two Final Four appearances. In 1979 he joined George Keogan in being elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame.

John Wukovits is a World War II historian who has written seven books about that conflict. Also a sports fan, Wukovits enjoyed researching his father’s 1935-38 teams.