Editor's Note: This piece is part of "12 Days of Classics," a holiday series drawn from the magazine's archives and published at magazine.nd.edu from Saturday, December 22, 2018, to Wednesday, January 2, 2019. Merry Christmas!

I first encountered It’s A Wonderful Life about 30 years ago at Notre Dame. In our sophomore or junior year, one of my friends was shocked to learn that I, the film buff in our group, had never even heard of this classic holiday movie. So when WGN aired it near Christmas, he reserved the Zahm Hall basement party room and we invited our friends to the screening.

We loved the movie. It was great to be with these friends and watch the story of a man who did more good than he knew. When the movie ended, after his friends had come to George Bailey’s rescue, someone pointed to one of the Farley girls who, never one to hide her emotions, was crying profusely over the happy ending. This distraction gave the rest of us a chance to surreptitiously dry our own eyes.

That night in that room with those friends has remained part of my experience with the movie over 30 years of watching. And after all those viewings, and what I’ve picked up each time I’ve watched it, I’ve come to realize that the movie ends the way I first watched it: with friends.

As those friends and I were watching George Bailey’s life story, I’m sure we weren’t looking 30 years down our own road — and we certainly weren’t thinking of ourselves ever being as old as George was in the movie (an age we passed a decade ago) or thinking about the situations we would be in, with our own responsibilities, our own compromises. No, the 20-year-old me wasn’t looking forward, but the 50-year-old me is looking back, wondering: Have I become George Bailey?

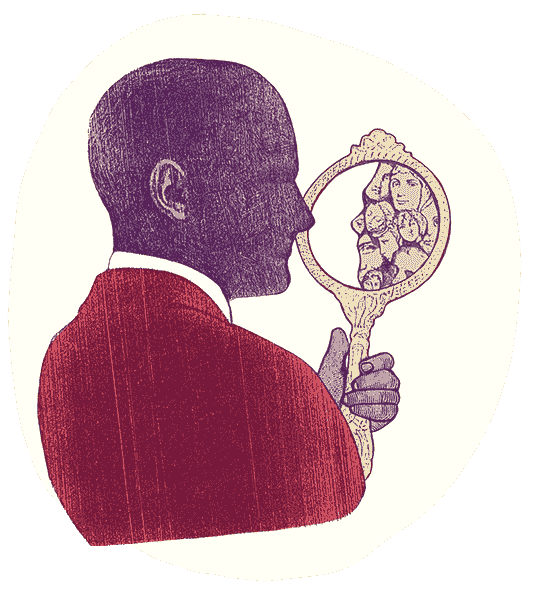

I believe It’s a Wonderful Life is like America’s mirror. I can’t be the only viewer who imagines I see something of my own situation represented there. It’s a story of a man of great promise and, if not promise, great dreams, who sets it all aside — the seeing the world, building things, getting rich, even lassoing the moon — and puts himself in the service of the common good. It’s a selfless act, and we all like to see ourselves in an unselfish light, forced by circum- stances to interrupt our plans.

Deferred dreams can be painful, though, and even noble George wasn’t always stoic in all of this. He was tempted by the evil Mr. Potter to take a better-paying job and close the Building and Loan. Potter pegs George: “George Bailey is not a common, ordinary yokel. He’s an intelligent, smart, ambitious young man who hates his job, who hates the Building and Loan almost as much as I do. A young man who’s been dying to get out on his own ever since he was born. A young man — the smartest one of the crowd, mind you — a young man who has to sit by and watch his friends go places because he’s trapped, yessir, trapped into frittering his life away playing nursemaid to a lot of garlic eaters.”

When Potter ends this description with “Do I paint a correct picture, or do I exaggerate?” George may sit silently, but we viewers know the answer.

George isn’t silent on the Christmas Eve when Uncle Billy has lost the Building and Loan’s deposit and the books are out of order and there’s a risk of fraud. When he gets home that evening after a day of scandal, he’s inundated with the day’s routine news from his wife and children, who are oblivious to his stress and ignorant of its cause. After stewing during several minutes of too much good cheer, he finally blows up in his living room and violently kicks over a table that holds a model of a bridge, his long-deferred dream that never came true.

Dreams are a part of the air in college — they’re woven into the promise of school and might as well be in the course catalogs. We go to college to create or fulfill dreams, and so, as students, we might have been particularly vulnerable to a movie about big dreams. Similarly, perhaps I was susceptible to the other cultural icon I adopted while at Notre Dame: Bruce Springsteen. Not long before we had our Wonderful Life party, Springsteen’s “The River” came out, and it included the line, “Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true, or is it some- thing worse?” The movie raises that question, too.

Was George trapped by a dream that didn’t come true? The 20-year-old me watched 20-something George go from dreamer to not-quite-40-something banker who’s not doing the important things he wanted to do. That youthful me ignored the important things George does — in being a good husband, good father, good citizen, good man. It took the angel Clarence to show George that he, too, was overlooking these accomplishments.

Clarence is the answer to a prayer but also to what is essentially a midlife crisis. Told by Potter that he’s “worth more dead than alive,” George lets his long-simmering frustrations boil over and reacts by calling his whole life into question — “It would have been better if I’d never been born at all.” The crux of a midlife crisis is to wonder if your life was worth it, whether you’ve done anything of consequence — something you’d be proud to tell your younger self about. Clarence’s mission in this somewhat inside-out A Christmas Carol shows George the impact of actions that are mostly everyday things, raising his kids, doing his job — as the Woody Allen line goes — of just showing up.

At the end of the movie, George reads the inscription that the newly winged Clarence wrote in a copy of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer: “No man is a failure who has friends.” Contrary to Potter’s taunt that the “riffraff” would run him out of town, George’s friends do show up, bailing him out with enough money to cover what was lost. But that happens only because George never realized his dreams. If not for George deferring his dreams, those friends would be living a Potter nightmare.

Interestingly, when Clarence tells George, “You really had a wonderful life,” he has only shown George what he had done for other people, not for himself. Having had those dreams, even if they didn’t come true, still shaped George. One might ask: Without those dreams, would he have been the man those friends would have wanted to rescue? Thus one answer to Springsteen’s question: Dreams that don’t come true don’t have to be a lie or something worse; maybe they are something else.

They may not have been angels, but the people in that Zahm Hall party room are still some of the best friends I’ve ever had. And in that room and in those memories and among those friends lies another solution to Springsteen’s problem. Simply enough, maybe too simplistic for some, an answer to dreams that don’t come true is friends — the distractions, shifted perspectives, altered opportunities, companionship, buffer, time and love that friends inject into life. The money from George’s friends solved his problem, but that was just a dividend from the time he’d invested in being a good man. It’s not the money piling up that jerks the tears at the end; it’s the flood of friends who keep pouring in.

No, I haven’t become George Bailey, and, given my reverence for the movie, there’s a certain sacrilege in suggesting it. My sacrifices and impact (and promise) don’t add up to his. But I’ve learned what he did. In my life, I’ve confronted problems that were insoluble, whether broadly dysphoric, like an unfulfilled dream, or wrenchingly real, like a death. Yet my friends and family were the solution, not by fixing the problem but by being there, by just showing up.

Patrick Gallagher lives in Aberdeen, South Dakota, where he works for the Catholic school system.