Sitting underneath a line of hanging laundry, I turned on my tape recorder to interview Sonia. We sat face-to-face in plastic chairs on swept dirt. Her weathered look made it hard for me to believe we were nearly the same age.

I had just graduated from Notre Dame and was in Nicaragua on a Fulbright Fellowship.

Sonia was a wife, mother of three and survivor of sex trafficking.

Quietly, matter-of-factly, she told me her story. She was 16 when she first prostituted in Managua, Nicaragua’s capital city. At the time, her mother was a domestic worker in Costa Rica and Sonia had a 6-month-old son. Sex work, legal for anyone 14 years of age or older, seemed to be her only chance at survival.

In her first year of sex work, Sonia said, she was beaten frequently. She turned to marijuana and alcohol to ease the pain. She also heard rumors of higher pay and better conditions in Guatemala. Two years and two more children later, Sonia was desperate for a better situation and chose to follow the rumored promise of a better life.

At age 18, escorted by an experienced sex worker who had been promoting Guatemala, Sonia and a handful of other girls crossed the Guasale River. As soon as the women entered Guatemala, their escort left. It was not long until a Nicaraguan man approached the group. For $50 per person, he offered to help the women find work in the city but refused to take any money at the time.

Sonia told me she trusted his offer because the man was Nicaraguan, like her. He gave the women clothes, shoes and food but did not explain that they would also be charged for these provisions, thus increasing their fees far beyond the initial quote of $50. The man took the women to a nightclub in Guatemala City, where Sonia would spend a year as a sex worker, futilely trying to pay off the debt she had incurred in a few short days, the sum of which only her trafficker knew.

The work conditions at the nightclub were far worse than Sonia had expected. More than 40 women lived in the three-story house: Salvadorians, Hondurans, Nicaraguans, Guatemalans, some as young as 15. The first floor was the nightclub. The second floor had small rooms used for sexual services. On the third floor, the women bathed in open air while the owners watched. Sonia was under surveillance 24 hours a day. When immigration officials appeared at the club, the minors and undocumented workers would pass through a secret metal tunnel to a private home next door. Sonia explained that the only workers allowed to step out of the club were veteran workers who had earned the confidence of the club owners.

The owner and other workers were constantly telling Sonia that other nightclubs were like prisons — women would be “locked in” if they misbehaved, punished for two or three days. The owners also claimed that in some nightclubs food was passed under the door like in prison.

In an effort to prevent disease from slowing business, the owners of the club frequently took the women to a local health clinic, trusting they controlled their workers enough to assure silence during confidential exams. But Sonia formed a relationship with the clinic’s nurse, who told Sonia how to free herself from her life of slavery. She handed Sonia a bus schedule and told her it was her choice whether to stay in Guatemala City or return to Nicaragua. At this point, Sonia was allowed to leave the club one day a week. After a year at the club, Sonia saw a way out and caught the bus back to Nicaragua.

In the months to follow, I heard story after story of coercion, fraud and exploitation. Catholic Relief Services (CRS) sponsored my efforts. During the day, I translated interviews in the CRS office as the organization worked to address the severe poverty surrounding us. At night, I accompanied social workers with another agency handing out condoms to Managua’s prostitutes, the women who would not likely live to see economic development efforts take root.

It was in Nicaragua, far from home, that I began to understand my own country. I saw the great disparities of North and South, and came to believe that the decision to leave home was all too often a choice of survival. Immigration decisions are not made lightly; just as Sonia had risked her life to go to Guatemala in search of something better, people risked their lives every day to come to the United States. Indeed, like every American family, mine is also an immigrant story — one that was woven through three generations before me.

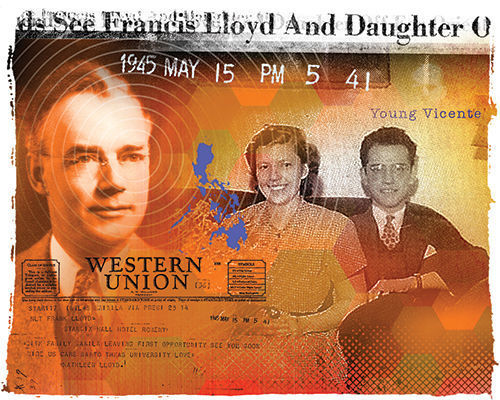

My grandfather, Vicente Gurucharri, grew up in the Philippine Islands, the son of a wealthy Filipino landowner. In 1936, he had a fortuitous meeting with Frank Lloyd.

As the United States was struggling to recover from the Great Depression, Lloyd was traveling the world on an unprecedented mission — to find wealthy foreign students who wanted to study at Notre Dame. Lloyd saw these students — who could afford to pay Notre Dame’s full tuition — as an aid not only to the University’s immediate finances but also its long-term economic well-being.

As Notre Dame’s comptroller, Lloyd was responsible for the financial health of the University. He was also an affable, paternal man who believed his obligation to Notre Dame extended beyond the balance sheet. During summer recess, Lloyd personally answered a thousand applications for student employment. He was moved by the University mission, and his commitment was perhaps best captured by a quote in the 1934 Dome yearbook: “To know him is to admire him.”

In the midst of the economic uncertainty of the 1930s, Lloyd proved to be a creative fundraiser. He used money from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Federal Emergency Relief Administration (later renamed the Works Progress Administration as part of the New Deal) to fund landscaping projects to employ Notre Dame students. He marketed the first official University merchandise to alumni — drinking glasses with the Notre Dame insignia on them. He also supported early efforts to encourage college savings plans for families.

By the time he proposed an exotic-sounding recruiting trip to the Orient, the trustees had faith that Lloyd’s efforts served the economic health of Our Lady and offered their blessings.

Vicente’s father, my great-grandfather Don Pablo “Lolo” Gurucharri, was equally ambitious. An immigrant himself — a stowaway from the Basque region of Spain — Lolo had quickly accumulated enough land to launch him into the Philippine elite and earn him invitations to the kind of social functions Frank Lloyd would attend to recruit students. At one such function, Lolo cornered Lloyd and insisted ND admit his son. Although Lolo was wealthy in the Philippines, he knew the United States could offer his Basque-Filipino son more than just money. He knew it was the land of opportunity.

Lloyd was concerned about Vicente’s English skills, but Lolo persisted until Lloyd made the call to secure Vicente’s admission.

It was an audacious time to be investing in foreign students. As the country slid deeper into the Great Depression, unemployment in America was at 17 percent and climbing. New immigrants increased the labor supply, adding to the competition for quickly disappearing jobs.

Meanwhile, new laws were changing the immigration landscape. The 1924 Immigration Act limited the number of immigrants admitted annually to just 2 percent of the number of people from that country already in the United States, and it excluded immigrants from Asia. But in 1936 the Philippines was still an American colony, thus making the path clear for Vicente Gurucharri. My grandfather was one of a few select Asian students allowed to enter the United States for college during the Depression.

Vicente applied for a Filipino passport, and in August of 1936 he arrived in South Bend with one suitcase in hand. He went on to serve as treasurer of the Notre Dame chapter of La Raza and fought in four championship rounds in the annual Bengal Bouts boxing tournament.

His charm and success did not go unnoticed by Lloyd’s daughter Kathleen. By Vicente’s senior year in 1940, the two were engaged to be married.

America’s approach to managing immigration was not born out of a vision or a strategy. Our immigration system is a patchwork of laws and policies developed in reaction to acute economic pressures and the existential questions of national identity that invariably follow. Over time, these disparate pieces have been stitched together into an unwieldy system that Congress now is attempting to resolve.

In fact, for a full century after becoming a nation, America had no immigration policy at all. Everybody who came to our shores could enter. The open door wasn’t always accompanied with a welcome mat — many new immigrants faced discrimination. But there were no laws preventing their immigration.

And many people came, including a wave of Chinese immigrants escaping instability in their home country. They came for the 1848-55 California Gold Rush and stayed to build the Transcontinental Railroad. But when the railroad jobs began to slow, Chinese immigrants were increasingly blamed for depressing wages and stolen jobs. During his 1852 re-election campaign, California Governor John Bigler urged Californians to "check this tide of Asiatic immigration.” He warned that the Chinese were incapable of becoming American and could never assimilate. It was out of this concern that our first law limiting immigration was born — the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act barred Chinese immigration altogether.

With its 1924 Immigration Act, Congress was attempting to implement the first permanent, sweeping system to regulate immigration. A nativist sentiment had emerged from World War I, gaining strength as the economy began to stagnate. In addition to the bar against Asian immigration, the 1924 law also combined and made permanent several existing pieces of immigration legislation, including a literacy requirement and a quota on new immigrants. The purpose was to preserve America’s supposed homogeneity, which, for a nation built on immigration, was already a fiction. The reality was that the notion of who “we” are had been in constant evolution from the earliest moments of our country, and the availability of low-skilled jobs was usually at the heart of the conversation.

From then on, U.S. immigration policy was a series of reactionary laws, ebbing and flowing with the tides of public opinion. Even laws that attempted to welcome newcomers were restrictive. The 1942-64 Bracero Program allowed laborers from Mexico to come to the United States but on a temporary basis only. The growth of the American economy drew immigrants looking for opportunity, and these immigrants helped meet our country’s labor shortages. By 1987, 5 million illegal immigrants were living in the United States. In reaction, Congress passed legislation to legalize 3 million of the 5 million, but over the next 25 years, the remaining 2 million ballooned to 11 million illegal immigrants.

Many worry that the challenges we face today are too great to enact a comprehensive legalization program for immigrants. Public education is in crisis and our health care system is being overhauled. Our economy is still recovering from the recession, and too many people are out of work or underemployed.

How can we legalize millions of people with any confidence that they will meaningfully contribute to our nation, or at least not drain our precious resources? These are valid questions generated by legitimate fears about our country’s future. The practicalities of fully integrating new immigrants, many of whom are poor, therefore warrant consideration and should not be confused with xenophobia. After all, they are concerns shared by citizen and immigrant alike.

My father, Vincent Gurucharri ’67, grew up in an environment fraught with such unease. Growing up in Sanford, Florida, he was Catholic and multiracial; he was a U.S. citizen but carried the stigma of an immigrant. He told stories of Ku Klux Klan rallies disrupting school field trips. His parents’ interracial marriage was not recognized by the state of Florida. Despite the daily challenges of navigating two worlds, he was determined to succeed.

His complex background left him isolated and ostracized at school. Academics became his anchor. Desperate for a launching pad to something better, he studied day and night. Eventually, he followed in his father’s footsteps and attended Notre Dame with the goal of going to medical school. He attended the University of Chicago Medical School on a full scholarship and continued on to become a general and thoracic surgeon. In his final year of training, he watched as his fellow residents were accepted into private practice while his mailbox remained empty.

The situation was so dire that he did the unthinkable: He asked his father if he could change his name to something more palatable for the American eye. Gurucharri was the name attached to the plantations that paid for his father’s Western education and that his Kansan bride adopted with pride. Yet it had become a seemingly insurmountable barrier to achieving his American dream.

Fortunately, he was eventually accepted into a private practice in Columbia, Missouri. He kept his name and went on to serve Missourians for more than 20 years, including a stint as chief of staff at Boone Hospital Center. His patients called him Dr. G.

In a small way, my father’s experience illustrates what makes immigration so hard. The truth is that the promise of immigrant success takes a generation. Maybe two. Maybe 10.

But in the end, it actually adds up to greater prosperity, not just for individual families and communities but for our nation as a whole. In fact, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that enacting a comprehensive immigration reform bill could reduce the national deficit by $197 billion in the first decade and by an additional $700 billion in the second decade. Here’s the 10-year logic: legalization increases immigrant wages and increased wages lead to new federal, state and local tax revenues. The Center for American Progress estimates that immigrants’ contribution to Social Security alone would increase state tax revenues by $748 billion by 2033.

Costs associated with legalizing 11 million news residents and citizens, including spending on health, education and other public services, would be offset by the increases in tax revenue, which could lead to increased public spending on education and job creation. In sum, legalization would be a steroid shot to the economy.

Additionally, immigrants help meet the demand for high-skilled talent in critical fields. High-skilled immigrants often can provide the right skills at the right time and in the right place. For one thing, high-skilled immigrants are more mobile and can go where the jobs are. The Brookings Institute found the demand for H-1B visas, the type of visa used for high-skilled immigrants, is highest in metropolitan areas where unemployment is already low. Immigrants are critical to maintaining our global leadership in innovation, which in itself is an engine for continued economic prosperity.

Such optimistic economic projections assume a certain level of assimilation, which is not easy or automatic for most immigrants, or even their children. It is especially difficult for low-skilled immigrants, who may not have the language or cultural skills needed to thrive in a new society. In a 2004 article in Foreign Policy magazine, “The Hispanic Challenge,” political scientist Samuel Huntington raised such concerns. He wrote, “The persistent inflow of Hispanic immigrants threatens to divide the United States into two peoples, two cultures, and two languages. Unlike past immigrant groups, Mexicans and other Latinos have not assimilated into mainstream U.S. culture, forming instead their own political and linguistic enclaves — from Los Angeles to Miami — and rejecting the Anglo-Protestant values that built the American dream.”

Such fears have been raised throughout our history about every group of immigrants that has settled in our nation. Would Germans learn English? Could Irish Catholics, loyal to a foreign pope, ever embrace American democracy?

The answer so far has been “yes.” David Leonhardt of The New York Times recently reported research suggesting Latinos, the largest group of immigrants to arrive in the last century, are following the trajectory of previous waves of immigrants to the United States. A Pew Research Center reports that the median income of immigrant Latino households trails the national median by $24,000, and yet for second-generation households, that gap is only $10,000 — a stunning increase in the span of just one generation. And 26 percent of second-generation Latino immigrants marry someone of a different ethnicity.

Today, we’re at a different point from when my grandfather set foot on Notre Dame’s campus, or even when my father set foot in Columbia, Missouri. Our system is more broken than ever, and change seems to be harder than ever.

Eleven million people are living in the United States without legal status, 63 percent of whom have been here for 10 years or longer. This shadow class provides needed low-skilled labor in our agriculture, construction and service industries, among others. These are the people who pick our fruit, build our homes and care for our children.

Undocumented people pay taxes. Undocumented immigrants pay sales tax and property taxes, directly if they own a home or indirectly if they rent. Income is withheld from their paychecks just as it is for the legal population. The Social Security Administration estimates that about 75 percent pay taxes that contribute to the overall solvency of Social Security and Medicare, yet they are not able to receive benefits. They can’t start legal businesses or support schools. They may hesitate to report crime or public health threats for fear of deportation. The militarized border means they can’t even leave. Families are permanently separated. Companies often cannot hire much-needed talent. And communities don’t have the financial resources they need to provide the educational and support services to help new immigrants thrive.

Meanwhile, no fence will keep people from trying to immigrate to America. The disparity of wealth between the global North and South means people will continue to risk their lives to come to our country — and their desperation means they will continue to be exploited by smugglers and traffickers. U.S. Customs and Border Protection documented 463 deaths on the U.S.-Mexican border in fiscal year 2012.

Our nation’s lawmakers on both sides of the political divide have accepted the need for immigration reform. However, how that is accomplished is still up for debate.

In June 2012, the Senate passed a bill with an eye to comprehensive reform. If this particular immigration bill became law, it would overhaul a complex multi-agency system to more effectively regulate the flow of migrant labor to and from the country, and would put a permanent end to illegal immigration. The bill would strengthen enforcement — both at the border and in the interior — by amplifying current efforts and expanding efforts to crack down on employers who hire undocumented workers. Reform would remove the barriers to legal immigration and support our economic interests by streamlining immigration policies and procedures. Most controversially, the bill would allow qualified undocumented people to apply for legal permanent residency and, ultimately, citizenship. The true power of this bill is that it provides a comprehensive solution to fixing a system of problems.

If implemented, an estimated 10.4 million undocumented workers would become permanent residents, and an additional 1.6 million temporary workers and their dependents would be eligible to enter the United States.

While few would deny the system needs fixing, in the context of enduring economic uncertainty, such a dramatic resolution can seem like too great a gamble. And in fact, the immigration effort stalled when members of House of Representatives, eager to respond to constituents resistant to large-scale change, dismantled the Senate-passed bill into individual pieces. Republican leadership argued that it’s better to take a measured, piecemeal approach, passing individual bills instead of solving all aspects of the problem at once. The first priority for these legislators is to expand border security programs — an effort that runs concurrent to state-led enforcement efforts.

As has happened before in our nation’s history, the anxieties caused by an economic downturn and heightened national security concerns have shaped our immigration discussion. These anxieties play out most conspicuously inside the Beltway, but they can also be found in every town in America. While Washington may seem particularly broken today, on the subject of immigration our system has never been particularly farsighted.

What my own family’s story tells me, and what so many other immigrant stories tell us, is that this is an issue that impacts all of us. Immigration is fundamental to the American community. While the debate may stall inside the walls of Congress, it will undoubtedly continue in communities across America. If we look at our personal and national histories, we may begin to change the way to discuss immigrants in America. We may begin to describe immigrants as our fuel for innovation, our labor force to spur economic growth, even a critical tax-base. They have always been part of the American story and they always will be.

This should be a welcome part of our national fabric. To achieve something valuable, that honors the deepest values of our nation, each of us must first look within ourselves and challenge our own ideas, biases and assumptions. And maybe we will find ourselves taking a leap of faith similar to Frank Lloyd’s.

Ann Gurucharri Saudek is a homeland security consultant specializing in strategy and change management. Previously, she served as a legislative advocate for immigrant victims of domestic violence, sexual assault and human trafficking. A Fulbright Fellow and graduate of the Harvard Kennedy School, she co-wrote “Justice for All: Mexican Communities Take Justice into Their Own Hands,” published in ReVista Magazine.