On the slopes of Mount Lebanon, overlooking Beirut to the west and the road to Damascus to the east, lies something wonderful and unlikely: green, flourishing vineyards, just above the village of Bhamdoun. Their existence restores an ancient tradition of the people and brings justice, in the words of its owners, to the land.

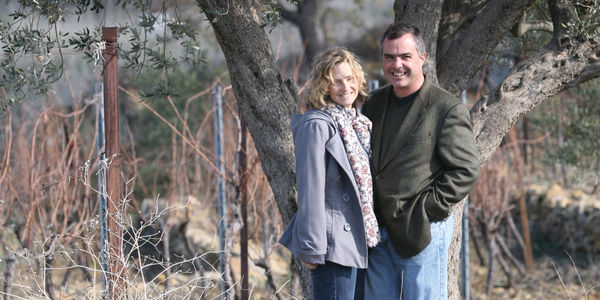

The winery attached to these vineyards, Château Belle-Vue, is the project of Jill Boutros ’88 and Naji Boutros ’87. Naji was born in Bhamdoun to a Greek Orthodox family at a time when the village and its mild mountain climate were renowned for being, says his wife, Jill, “a place where you could go to heal.” It was home to a French embassy, 35 hotels, five Christian churches, two mosques and a synagogue. In this healthful, polyglot place, all the villagers would donate money, no matter the petty spites that might divide them, to offset the expenses of funerals, so no family would have to endure the cost of loss alone.

Then, in the early 1980s, when Naji was in his teens, Lebanon disintegrated. Political and sectarian violence flooded the country. The sunny slopes, once a shade of peace and convalescence, were inundated with bombs and scenes of fighting. Naji joined one of the local militias, but his mother sent him to France when he turned 17. Shortly after, 350 Christians in Bhamdoun were massacred. The embassy, hotels, churches, mosques and synagogue were destroyed. The trauma of such destruction lingers. Even now, says Jill, when it comes to earning and keeping trust, there is zero margin for error. Moreover, it is often difficult to find people from that area who plan for the future.

Naji, however, was not one of them. He had earned scholarships in high school to study electrical engineering abroad, and he fell in love with Notre Dame. He also fell in love with Jill Johnson, a young woman from Minnesota majoring in economics. Jill remembers that a mutual male friend had arranged their meeting — a fact the women matchmakers of Bhamdoun find amusing. After graduation, the pair earned master’s degrees at different schools and married in 1990. Naji began work at Merrill Lynch in New York and Jill taught school in Montclair, New Jersey. Eventually the couple moved to London; Naji sent to open a new office, Jill to teach at the International School. The young couple had a son, Philippe, the first of four children.

And yet Naji never forgot his beloved Lebanon. He and Jill visited Bhamdoun in 1994, during the Syrian occupation. “He had a clear image of what the village was,” says Jill, since he grew up in Hotel Belle-Vue, the oldest hotel in Lebanon, built by his great-grandfather. What he found shocked him. Ninety percent of the village had been destroyed. Of some structures, not a single stone remained. The side of the mountain, however, still showed signs of civilization: its ancient carved terraces. “This got him thinking,” says Jill. Naji started to ask himself how they could bring people and life back to the village. As they continued to live abroad, small epiphanies started to occur. Finally, standing in front of the altar of the Duomo in Milan in 1998, Naji noticed a carved cedar of Lebanon. Jill says he took it as a final omen.

In light of that image from the Song of Solomon, it would be tempting to characterize what happened next as Naji’s bounding over the mountains like a stag toward his beloved. The reality was more complicated. Moving back to Bhamdoun in 1999, this time permanently, Naji and his family found the village still a physical wreck. The climate was as mild and inviting as ever, but the surrounding area, so close to Beirut, was zoned for residential development and concrete. Upon hearing of Naji’s plans to kick-start the local economy and replant the vineyards using only local craftsmen, people in Bhamdoun were unsure.

But sometimes something happens on the road to men and women of vision and sacrifice: They find helpers. For Naji and Jill, help came in the form of a local farmer named Joseph Khairallah. He had grown up tending the land with his father, grandfather and donkey. Like Naji, he had left Lebanon as a young man and did not return for many years. When he heard people talking of Naji’s vision, Joseph insisted he would plant and work to make the valley green again. “The land of our nation is full of memories!” he had said with a smile. When Jill speaks about him, her eyes fill with emotion. “He was very true,” she says. “His hands were permanently caked with dirt. He had no artifice, never pretended anything. And he believed finally you should bloom where you’re planted.”

And so in April of 2000, Joseph and Naji planted 3,000 vines. It was the start of a new millennium, and a new beginning for Bhamdoun.

Like the people, the soil of Belle-Vue is varied and complex: stony, mineral-rich and calcareous, and arranged in layers of hard clay, limestone and silt. The grapes, too, are varied and classic French varieties such as cabernet sauvignon, syrah and petit verdot. The winemakers even grow sauvignon blanc and viognier to make a delicious little white. Their first harvest came in 2003. The resulting blend of cabernet sauvignon and merlot, “La Renaissance,” was voted Gold Best in Class at London’s International Wine & Spirits Competition in 2007. While their wine business grew, so did other projects. In 2009, Naji founded his own private equity firm, Edge Capital. Jill conceived a book project, Lebanon A to Z, which she wrote collaboratively with friends to represent the customs of Lebanon’s diverse communities.

Along the way, their efforts and approach attracted the notice of winemaker Diana Salameh. She had grown up in a nearby village, had studied in a famous oenology school in Dijon and had worked at two prestigious wineries. Hired by Château Belle-Vue in 2005, the only female oenologist in the country found herself at the forefront of the resurgence of Lebanese viticulture. From 17 wineries in 2006, says Jill, there are now 35 and counting.

Château Belle-Vue had not only become a successful winery, it had become a new beginning for its region. The company’s 400,000 square meters of vines were placed in the care of all the major families in the area. The local boys, under the direction of old Joseph, tended the vines and have learned to care for the soil using only organic methods. In 2012, a woman who also wanted to return to her roots joined the team. Esperanza Geara, a specialist in agricultural engineering and horticulture, had studied oenology and had worked as a winemaker in Chile, New Zealand and Spain. She is now overseeing a new bistro, tasting room, and bed and breakfast facility at the winery.

The new buildings will also house a Center for Peace and Reconciliation. The recent war in Syria has issued in a new flood of refugees, millions of them, moving down the Damascus Road past Bhamdoun. Their presence is a source of widespread concern among the Lebanese, but Naji and Jill continue to bring the different communities together into a new and shareable heritage, a common good. Their wines are thus a literal expression of the land’s physical and social potential.

Current production is at 20,000 bottles. Naji and Jill donate $1 from every bottle to fund scholarships for needy children in the village. Every Christmas, they assemble special baskets of artisanal products made by local families to sell to their wine subscribers, the proceeds of which go a long way to support those families. They established the Belle-Vue Community Library, which has thousands of volumes for adults and children, and provides a gathering space for young adults. Local boys are now working with Syrian refugees in the vineyards. The result of their collaborative work will affect the success of the community years later, when the red blends are released for sale. “I’m proud to say we have made an impact on the lives of so many,” says Naji. “Belle-Vue is a beacon of good news.”

They are changing their part of the world. Out in the vineyards, Jill says, Naji can finally breathe. She smiles fondly at the thought of the local boys, the future, who work with him. Joseph died this past October, doing what he loved and at peace among the ripening vines. When the local boys heard the news, they came up the hill, no matter what their creed or family, to do, they said, whatever they could. The whole community poured out to help with the funeral, as their families had done before the war. “The boys together wove a blanket of vines for his casket,” she says. “They never imagined they would have this kind of connection.”

Jill thinks on all this and smiles. A foreigner in Lebanon, she feels at home. The families around them are strong and connected to the land again. “I want my children to be appreciative people,” she says, which means immersing them in a dense web of natural relations and natural life and giving them roots. Cities make her sad. There are parts of Beirut that still lie in ruin. People there are disconnected. How very different such places are from Belle-Vue. In the cities, “You may hear birdsong,” Jill says reflectively, “but never see them fly by.” Naji is more emphatic. “The bottom line, dear friend, is this is a labor of love! Love, love and love!”

Anthony Monta is the associate director of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies.