I hopped off the plane from Kenya, stepped onto American soil (actually carpet) and sat down in the terminal like someone sitting down to watch his favorite rendition of his favorite play.

A man with an iPhone was munching a Big Mac, a teenager with a ThinkPad was browsing Facebook, a child with light-up shoes was stumbling around, mesmerized by her heels and unfazed by the long legs leaping out of her way.

“This is America,” I thought — the stairs know how to climb (escalators), the floors know how to jump (elevators), the walls know how to speak (intercoms), the ground wears clothes (tiles, carpets), the toilets have blinking, red eyes (automatic sensors) and so do the doors.

That man eating his Big Mac is sitting in Chicago, but when he bites down his teeth are in Argentina. He picks up his phone; now his voice is in Seattle. He browses the web, and his eyes are in Hong Kong. He turns up his iPod; his ears are now in 18th century Vienna.

And that girl with the ThinkPad is sitting in the airport, but when she taps her fingers she’s dancing in a club with her friends. She checks her emails, and she’s chatting with a professor on the quad. She closes the screen; now she’s back in the airport, alone.

These are my people. Americans. Sons and daughters of immigrants; mothers and fathers of magic. We are a fantastic, dreamy people — creatures with faraway eyes and sanitized hands. We have mastered the microchip and set our footprints on the moon. We can make a dead heart thump in a living chest and teach a blurry eye to read the fine print. We can rain bombs on people who don’t think like us and rain food on people who don’t eat like us. We are as compassionate as we are cruel, as much a brother to the nations as we are a bully, working as hard to shut out the world as to save it. And we are religious. Standing Tall, Wanting More and Being Free are our gods.

My reflection was interrupted by the man with the Big Mac. He had dropped his last fry behind a chair and couldn’t reach it. His face was red, and he was threatening the chair.

“I’m back,” I said — back in my country, back with my people, back with my fries.

Culture shock. It happens. It used to devastate me. I would walk into supermarkets and think of Naisanga — she died of hunger. I would pour fuel into the lawnmower and remember Kigozi — he caught drops of fuel from leaking lorries for a living. I would flush the toilet and remember Father Stefano — he ripped out his toilet and turned it into a well. “It doesn’t feel right s- – -ing in water when your neighbors are dying for it,” he said.

But you love a culture for its beauty, not its perfection. Four years ago, before I left the States, that man and his fry would’ve been on my blacklist. But now I couldn’t help but feel some patriotic affinity for them — even solidarity. As Rumi said, “A thirsty man sees God in his cup.” If that’s true, maybe it’s also true that a man abroad sees God in his home.

My parents offered to pick me up from the airport, but I opted for the bus. Not because I don’t cherish their company — I do, especially when Mom’s navigating or Dad’s in traffic — but I like the bus because it gives me more time to adjust.

“In times past,” says The Shadow of the Sun, “when people wandered the world on foot . . . the journey itself accustomed them to the change. The voyage lasted weeks, months. The traveler had time to grow used to another environment, a different landscape, a different climate. Today, nothing remains of these gradations. Air travel tears us violently out of snow and cold and hurls us that very same day into the blaze of tropics.”

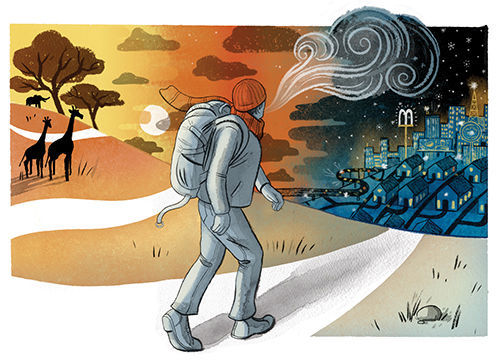

Or, in my case, tears me out of the tropics and hurls me into the snow, steals me from the ancient and returns me to the modern, cuts me from being and pastes me to having. Africa to America — in one day.

But the bus gives me a bit more time to cross this threshold. I appreciate that time.

The second reason is because going home is my last small adventure before starting another big one: being home. When I get home, it’s never the same as when I left home. As I’ve been traveling the world, my home has been traveling through time. Accepting that is an adventure in itself.

So I step onto the Coach USA bus and find a window seat. A deep warmth comes into my bones and a restlessness to my nerves. I’m almost home. I can feel it. It’s a fish-in-the-water type of a feeling. “When I return home,” I scribble on a napkin, “home returns me.”

I turn off my iPod and press my ear to the chilly window, listening to the familiar sounds of a familiar place. I open Robert Ellsberg’s Modern Spiritual Masters: “Why should the song of the lark in the wheat fields, the buzzing of the insects in the night, and the droning of the bees among the thyme, nourish our silence, and not the crowds in the street, the voices of the women in the market, the yells of the men at work, the laughter of the children in the garden, and the songs coming from the bars? All of these are the noises of creatures advancing towards their destiny, all of this is the echo of the house of God in order or in shambles, all of this is the sign of life encountering life.”

I’m here to listen to this music, the music of cars honking their way toward their destiny and of fingers flipping open their phones to encounter other lives. It’s all happening in the echo of the house of God, and I’m sitting in the middle of it, on a bus, contemplating the enigma.

After an hour, the bus turns off the highway to make our first stop. There are five stops. Mine’s the last. We pass a row of snowy driveways. I think of Mara, my big sis. We used to be the early morning snow-shovelers. We would inch our way down the driveway with moist cheeks and warm souls — our faces lost in drifts of white, our spirits lost in puffs of powder. We’d come inside and spot the boiling milk — our boots were dripping.

Some passengers get off the bus at Highland, Indiana. As we continue, a line of evergreens follow us. I think of Steve Henderson, my long-time pal. We used to scale the tallest trees. We were expert climbers with sappy hands and bark-scraped knees. We always reached the top. Wrapping our lives around the branches we held, we were closer to the sky than to the earth. When my mom called us down, we never came. Not until my dad called.

We pass Tire Rack. I think of Dad. I was 15 when he taught me to drive. We were in the Harris Prairie parking lot, in the Toyota Corolla. No radio now, only concentration. Mara’s shin guards reeked in the back seat. Her air freshener had given up and hung itself from the rear-view mirror. “My life is in your hands,” Dad said. I accelerated. Destination: manhood. The engine roared, the wind blew, the thrill was totally awesome. “You’re in park,” Dad said. “Put it in drive.”

We’re almost there. I see the South Bend exit. We pass a pond, and I think of Saint Mary’s Lake. I used to toss pebbles into it, watch the ripples expand. “That’s home,” I write on the worn-out napkin. “Home is the expanding circles of a lake.” It slowly includes more people, more places, more memories. “And home is the last gulp of air the stone takes before plunging into the water.” It’s what gives us the strength to live in the world. “And home is the air itself who — for a split second — carried something heavy in its fragile arms, who — when the time came — let it go, and who — ever since that time — waits eternally for it to come back.”

I’m almost back, back to the lakes and the rocks and the air from which I originated. We’re headed up Angela Boulevard, driving by Saint Joe High. The bus points its finger to the Golden Dome like Babe Ruth. Home run.

“Last stop!” the bus driver yells as he pulls into the Hammes Notre Dame Bookstore. I look out the window. Dad’s waiting for me. He’s got the Toyota running to keep it warm. It’s in park. I jump out of the bus, forgetting my bags, and run into his arms. My eyes see a dad in him, but my arms feel a home. So I hug him as if he’s something in between — as if he’s a ripple who gave me life, a stone who taught me depth, a wind who let me go. And his eyes see a man in me, but his arms feel his child. So he hugs me as if I’m something in between — as if I’m a ripple that went too far, a stone that sunk too deep, an eternity who finally returned.

“Welcome home,” he says, holding back the tears. “Welcome home.”

Michael McDonald is a student at Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. He returned to South Bend in August 2013 after a four-year “graduate school for his heart,” when he worked alongside L’Arche founder Jean Vanier in France and published three books on social justice in Kenya.