Ara Parseghian, whose Fighting Irish teams won two national championships during his tenure as head football coach from 1963 to 1974, died early this morning (August 2) at his home in Granger, Indiana. We republish this interview piece written in 2014 by then-alumni editor Kevin Brennan ’07, along with stories about the Parseghian family’s battle against a rare disease and their ongoing contributions to scientific research at Notre Dame, in his honor. — The editors

It happened in Yankee Stadium of all places. On Thanksgiving Day in 1963, in the same ballpark where Knute Rockne and Frank Leahy recorded some of their greatest victories, the storied Notre Dame football program hit rock bottom.

By surrendering the game-winning touchdown with less than four minutes to play, the Irish fell to Syracuse in the final game of a 2-7 season, the latest in a string of disappointments for Notre Dame’s national fan base. The team had not posted a winning record in five years, an unprecedented drought. In one of the earliest manifestations of a pattern that seems to repeat itself whenever the program slides into a sustained period of mediocrity, the national media and even some supporters wondered if Notre Dame, with its commitment to academic excellence, would ever win again.

The football coach at another academically elite, private university in the Midwest rejected that notion. Over the previous eight seasons, Ara Parseghian had steered Northwestern, a perennial loser, to one of the most successful runs in school history, including four straight wins over more talented Notre Dame teams. And now, he wanted to revive the Fighting Irish.

“I saw talent there,” Parseghian, now 91, explains as he reflects on his decision to pursue the Notre Dame head coaching position. “And maybe they didn’t have it lined up properly.”

It’s been 50 years since Parseghian, who lives five miles from Notre Dame Stadium, arrived in South Bend. Fifty years since his first team under the Golden Dome produced one of the greatest single-season turnarounds college football has ever seen. And 50 years since the Fighting Irish suffered one of its most devastating losses.

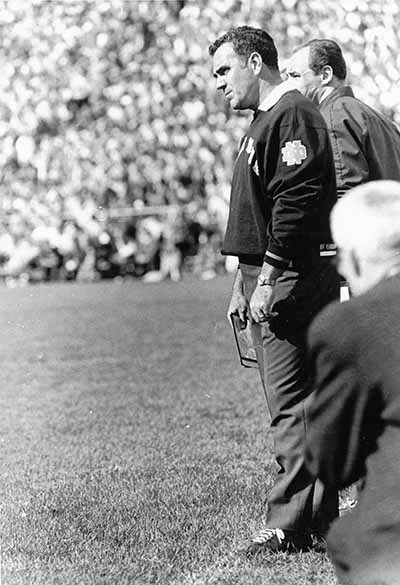

When the Notre Dame job opened up at the end of the disastrous 1963 campaign, Parseghian sold ND administrators on his demonstrated ability to succeed at a school that maintained high academic standards for its student-athletes. By December, Parseghian, 40, felt a chill go up his spine as he drove up Notre Dame Avenue and realized the incredible responsibility that comes with being the head coach of one of college football’s premier programs.

From his first days on the job, the new coach sensed a yearning circulating throughout campus. “Everybody was hungry,” Parseghian says. From the players to the administrators to the rest of the students, Notre Dame craved a winner with a passion Parseghian hadn’t experienced at Northwestern or Miami of Ohio, his alma mater and the first stop in his coaching career.

Parseghian and his coaches went to work. During spring practice, players noticed an immediate difference in the attention paid to the smallest details. “When you screwed up, you’d be waiting to hear your name be screamed from all the way across the field, even if you were 60 yards away,” says starting safety and kick returner Nick Rassas ’65, who had turned down eight scholarship offers to walk on at Notre Dame three years earlier. “He missed nothing.”

Every player got a fresh start as Parseghian and his staff reimagined the roster. Jack Snow ’65, a seldom-used halfback, shifted to wide receiver, where he’d win All-America honors at the end of the 1964 season and go on to a 10-year professional career. Running backs Paul Costa ’65, Pete Duranko ’66 and Jim Snowden became linemen. But what about a quarterback?

The feedback Parseghian had heard on John Huarte ’65 was negative. The soft-spoken signal-caller hadn’t played enough to earn a letter during his junior season. But he had one more opportunity to make his mark at Notre Dame.

- Ara Parseghian, 1923-2017

- Echoes: When the Irish got their fight back

- Soundings: The time of my life

- Life in the Abyss

- Riding to the challenge

- A cruel disease, a glimmer of hope

- The Boler-Parseghian endowment

“They announced that everybody would have a chance to show their skills,” Huarte says. “He ran us all through drills to see who had strong arms, to see who had quick arms, to see who was accurate.”

It became clear to Parseghian that Huarte gave him the best chance to win. Along with longtime assistant coach and close friend Tom Pagna, Parseghian groomed the quarterback all spring, attempting to restore his shaken confidence. Before the start of the season, Parseghian assured Huarte that he had the job, no matter what.

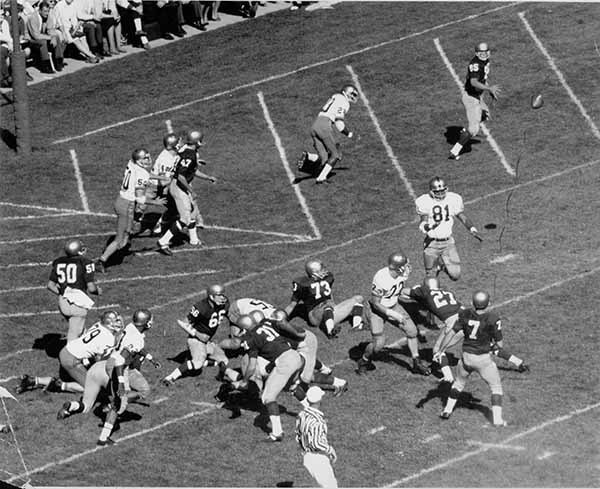

Huarte didn’t waste any time justifying his coach’s faith. Entering the first game of the season a decided underdog on the road against Big Ten power Wisconsin, the Irish moved the ball with ease, as Huarte passed for 270 yards and two touchdowns. The offensive explosion, combined with a staunch defensive effort, gave Notre Dame an eye-opening 31-7 win.

The Irish returned to an adoring campus. After a raucous pep rally in the fieldhouse on Friday night, Notre Dame walloped Purdue and star quarterback Bob Griese in the home opener, 34-15. Something was happening in South Bend.

Notre Dame destroyed its next four opponents, as Air Force, UCLA, Stanford and Navy combined to score a mere 13 points against the stingy Irish defense. “It just got better with every single game,” Rassas remembers.

The only close call came when the Irish, now ranked No. 1 in the country, traveled to Pittsburgh, where they pulled out a 17-15 win over the Panthers. Returning to form, Notre Dame cruised the next two weeks, beating rival Michigan State, 34-7, and downing Iowa, 28-0.

The college football world and the national media, including some of the same voices who had pronounced ND football dead a few months earlier, took notice. Parseghian’s face graced Time magazine’s cover. His quarterback made the cover of Sports Illustrated and emerged from obscurity to win the Heisman Trophy, a feat Parseghian still marvels at 50 years later. “To go from a nonletter winner, a nonstarter, to the Heisman Trophy winner in one season is unbelievable,” he says with a smile.

Just as unlikely, the team was one win from the national championship. Only a date with the University of Southern California in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum stood between Notre Dame and its Hollywood ending. The first half went according to script, and the Irish led 17-0 at intermission.

Parseghian and his players still have difficulty discussing what happened next. After USC cut the lead to 10, the Irish appeared to score from the 1-yard line, but left tackle Bob Meeker ’66 was whistled for holding on a call that replays showed to be, to put it kindly, questionable. In the next day’s Los Angeles Times, columnist Jim Murray attributed the penalty to an “official with a suspicious mind.”

The hold was the first in a string of controversial calls that went against the Irish. Five decades later, Parseghian sits up in his chair to re-enact a play from USC’s final drive, when Irish defensive end Alan Page ’67 broke through the line and wrapped up USC quarterback Craig Fertig, who desperately got rid of the ball as Page threw him to the ground. Parseghian maintains it should have been ruled a fumble or intentional grounding. “But what did they call? An incomplete pass,” the coach recalls with a chuckle.

On the next play, facing fourth down from the 15 with just over 90 seconds left, Fertig threw a touchdown pass to give the Trojans a 20-17 victory. Notre Dame’s magical season, along with the hopes for another national championship, had ended at the hands of its most bitter rival.

The locker room was “like a morgue,” says Rassas. Huarte couldn’t stop thinking about his coach. “I felt really bad for Ara. He had done such a great job of coaching,” Huarte says. “I really felt bad that we didn’t win the game for him like we wanted.”

Parseghian says he doesn’t think about the game much anymore. “You live with it. There’s nothing you can do to change it. But the very fact that I remember at this stage pretty much all that took place tells you the impact that it had.”

The healing began a few days later when the devastated team returned to South Bend. Turning onto Notre Dame Avenue, their buses stopped, engulfed by students and fans saluting their returning heroes. The students escorted the team to the fieldhouse for an impromptu pep rally, refusing to allow the loss to overshadow the incredible 9-1 season. “I’ll never forget that, ever, ever, ever,” Rassas says. “That’s one of the great memories of my lifetime.”

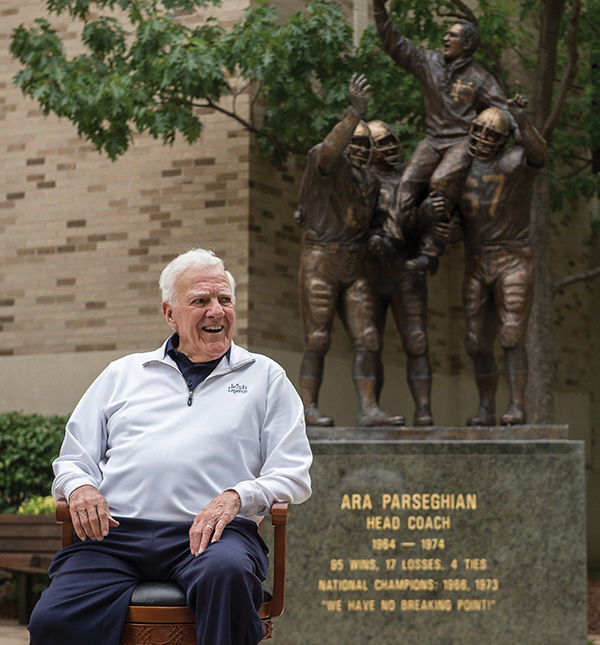

They hadn’t won the national championship, but the Fighting Irish looked nothing like the dejected group that left Yankee Stadium the previous Thanksgiving. The 1964 team defiantly returned Notre Dame to its place atop the college football landscape. Parseghian’s arrival ushered in the modern era of Notre Dame football and marked the beginning of a new golden age. Notre Dame went 95-17-4 and won two national titles during his 11 years as coach.

Reflecting on the legacy of that season, Parseghian deflects any invitation to boast, instead touting his players’ dedication and heart. “They wanted it,” he says. “Everything you told them to do, they would do with enthusiasm, and they couldn’t wait to do enough of it.”

The feeling is mutual. Parseghian’s former players gush about the way he treated them on and off the field, as well as the work he’s done later in life. Through the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation, Parseghian has helped raise awareness and millions of dollars for the fight against Niemann-Pick Type C, a deadly genetic disorder that claimed the lives of three of his grandchildren. “What a great man,” Huarte says.

Parseghian last coached a football game almost 40 years ago, but he hasn’t lost his passion for the sport. On fall Saturdays, he turns on two televisions in his living room and follows the action from noon until midnight. He never misses a Notre Dame game and has an unyielding faith that the Irish can compete at the highest level. But he knows he’ll probably never see anything quite like the magical fall of 1964.

“It was an exciting time for everyone,” Parseghian says. “It’s almost impossible to duplicate.”

Kevin Brennan is alumni editor of this magazine.