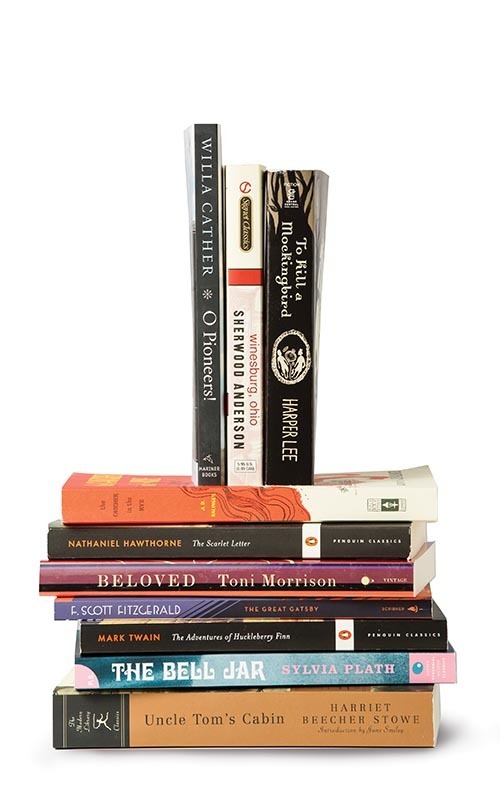

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

It almost doesn’t matter that Abraham Lincoln very likely did not greet Harriet Beecher Stowe in the middle of the Civil War with the remark, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!” because in a way she was the little woman who wrote the book that made that great war. This book stands, with Moby Dick, as the great novel of the 1850s, but crowds out Melville because Stowe’s story — approachable, unforgettable, above all fired with moral outrage — helped consolidate opposition to slavery in a nation whose literacy rate at mid-century was around 75 percent. The biggest-selling American novel of the 19th century, its impact was more nuanced than is sometimes realized, fostering stereotypes of blacks even as it attacked the slavery that defined their lives.

The Bell Jar

Breathes there a teenage girl with literary sensibilities and a sense of drama who is not moved by Sylvia Plath’s story of how Esther Greenwood, full of youthful promise, descends into depression? The Bell Jar was Plath’s only novel. Her short stories and poems, including those gathered in The Collected Poems, which won a posthumous Pulitzer Prize, endure well beyond her status as a feminist icon. But her novel’s poignant story continues to resonate, and not only among those who identify with the passage of Greenwood from magazine internship to madness. Indeed, its literary reputation has only grown since it was published in 1963 — and so has its impact.

The Great Gatsby

No list of candidates for the Great American Novel omits this F. Scott Fitzgerald classic, written in part to be included in lists of the Great American Novel. So many elements of this 1925 novel — the West Egg setting, the beguiling and repellent character of Jay Gatsby, the dazzling Daisy Buchanan, the green light at Daisy’s dock — beat on as elements of the American memory, not least because the book has been adopted for the cinema as early as 1926 and as late as 2013. “There are only the pursued, the pursuing, the busy and the tired,” Fitzgerald tells us, speaking perhaps of himself, perhaps of all of us.

The Catcher in the Rye

This J.D. Salinger masterpiece isn’t only a book, it is a genre. It is the “coming-of-age” novel against which all others are measured, and its opening (“If you really want to hear about it”) has become embedded in American folklore, and been adopted and adapted in songs and videos. Holden Caulfield, the central figure of the novel, is one of the most memorable characters in all of literature, examining in his crusade against “phonies” the meaning of life and helping tens of thousands of American youth — and adults — confront the difficult questions, or avoid them.

To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee published only one novel, but To Kill a Mockingbird may be the most widely assigned novel in American high schools, and Atticus Finch, the lawyer at the center of the story, is one of the most admired figures in modern American literature. “The one thing that doesn’t abide by majority rule,” he says in the book, “is a person’s conscience.” Published as the civil-rights movement was gathering force in 1960, this book is a portrait of a Southern town and an examination of the meaning of justice. In presenting Lee with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2007, George W. Bush described Mockingbird as the “story of an old order, and the glimmers of humanity that would one day overtake it.”

O Pioneers!

Willa Cather is one of the most beloved American novelists, her work sometimes miscast as regional fiction. Though she is forever identified with Nebraska, she was born in Virginia and wrote much of her work in Pennsylvania and New York. By examining and in some ways elegizing the pioneer Great Plains, she provided modern readers with a hardscrabble alternative to the shoot-’em-up West of cinema and cliché. This novel is one of her most affecting, a celebration of perseverance. And there seems to be no more beautiful last sentence in American literature than this one: “Fortunate country, that is one day to receive hearts like Alexandra’s into its bosom, to give them out again in the yellow wheat, in the rustling corn, in the shining eyes of youth!”

The Scarlet Letter

Of all the Nathaniel Hawthorne novels and stories, this may be the most enduring. A searing tale of adultery and betrayal in a colonial setting, The Scarlet Letter raises questions about guilt, redemption and justice. The scarlet “A” that hangs from Hester Prynne is one of the most chilling symbols in the American canon. This novel derives its importance not only because it examined vital issues in Puritan life — and abiding themes in our national life — but also because its wide distribution following its appearance in 1850 helped establish the novel as an important American art form.

Huckleberry Finn

This is the Great American Road Novel, the great vernacular novel, a great Southern novel, an exploration of the relationship between culture and morals, an assault on various forms of slavery — told by one of the great narrators in all literature. And, as a pure piece of literature, it’s innovative and surprising. As a road novel, it anticipates Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, one of the founding documents of the Beat movement, influencing hundreds of thousands who know its theme but have never creased open its binding or contemplated the meaning of the name of the narrator, Sal Paradise. But for all-around mastery, no book matches Huck Finn, a novel whose binding has been cracked open by almost every living American.

Winesburg, Ohio

In a century marked by great ethnic novels (The Natural, Love Medicine, Herzog_) and urban and suburban disillusion (_Rabbit, Run and American Pastoral), a collection of spare short stories set far from ethnic or coastal America may be the most evocative of the broad American experience. Published in 1919 by Sherwood Anderson and set in a mythical small town — Anderson even provides a map — this book is centered around the peregrinations and perspectives of George Willard, a young reporter in the town preoccupied with looking beneath the surface of the lives he encounters. By opening the book with a chapter called “The Book of the Grotesque,” Anderson signals that beneath the surface of the lives he examines is alienation and desolation, but most of all loneliness. In spare and stark language, Anderson scrutinizes the myth of the tranquil American small town and provides his readers with an unforgettable portrayal of the rootlessness of people rooted in their natural settings.

Beloved

Reared in an integrated community, educated at Howard University, shaped by Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner, celebrated at Princeton University for her teaching, Toni Morrison may be the greatest living American writer — and Beloved is perhaps her greatest work. Set in enslaved Kentucky and in free Ohio before and after the Civil War, and revolving around a woman who kills her daughter to keep her from a life of servitude, Beloved is, in every meaning of the word, a haunting novel. Her 1993 Nobel Prize citation — for novels “characterized by visionary force and poetic import,” giving “life to an essential aspect of American reality” — is an apt description of her most illustrious novel.

— David Shribman