Editor’s Note: Saint Damien, who ministered to leprosy patients on Molokai in the 19th century and died of the disease, has been the subject — or, to be more precise, his U.S. Capitol statue has been the subject — of some unexpected controversy in recent weeks. Our latest Magazine Classic is a story about a 2015 Campus Ministry pilgrimage to the site of Damien’s legacy.

There it is.

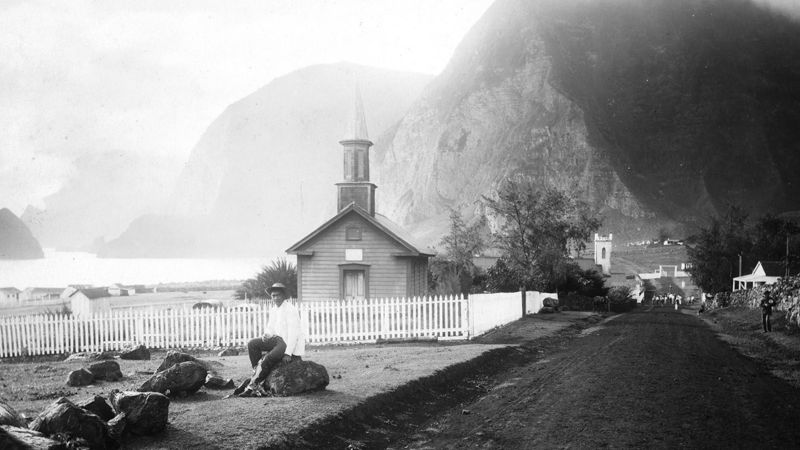

Illuminated by the first rays of morning sunlight, we see it. The leprosy colony. It’s why we’ve traveled here, to a place that is both paradise and prison. A place of life and of death. Of illness and of recovery. Of sin and of sainthood. Just 2,000 feet below us is Kalaupapa, an idyllic and lush peninsula jutting off the island of Molokai, Hawaii.

There we will find the graves of 8,000 patients who were taken from their homes and families, and shipped to these 12 square miles of isolation to succumb in quiet and anonymous agony to the effects of Hansen’s disease. They were sent away to die. Nine patients remain, waiting for their turn to be buried in the only land that would take them, to join the only community that would accept them.

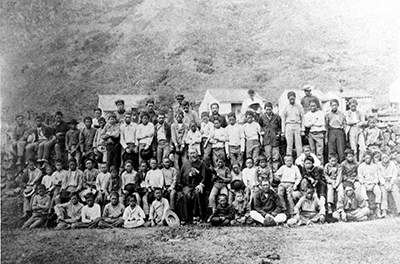

There, too, are the makings of two, maybe three, saints. Saint Damien de Veuster, a Belgian priest, spent 16 years from 1873 until his death in 1889 caring for and ministering to leprosy patients when no one else would. He volunteered to live with them, create order within the colony and bring God to the people, even if it meant dying among them. When he succumbed to the disease, Saint Marianne Cope and a group of nuns continued the legacy Damien had created. She would spend 30 years refurbishing the settlement, caring for the orphans and providing education for the patients.

The third player, the longest serving but least known, is Brother Joseph Dutton. A Civil War veteran and a Catholic convert, he came to join Damien after reading a newspaper clipping about his work. Dutton knew full well that after he set foot on Kalaupapa he’d never be able to leave. For 45 years he toiled with and for the patients in the colony, and has remained in relative anonymity, until now. But we’ll get to that later.

We, a group of 19 Notre Dame students and three chaperones, have been chosen by Campus Ministry to visit a site that formed these modern saints and literally follow in their footsteps. We’re asked to do more than sightsee and work on volunteer projects while on the island; we’re also asked to be open to conversion and grace as we each discern our vocation and aspire to sainthood. It is a tall and ambiguous order.

And so, the Friday before the March spring break, we find ourselves on a bus, barreling toward O’Hare airport at 5 in the morning, groggy, nervous and uncertain of what’s to come. It seems most of us signed up for the same reason: to see a part of Hawaii we may never otherwise experience. But as for what we hope to take away, that part is less clear.

After a long flight, an unexpected layover and a rocky puddle jump, Molokai’s dark green mountain tops emerge from the gray and stormy clouds. In open-mouthed awe, I wonder if this is how Damien felt when, after weeks, maybe months on a boat from Belgium, down around the tip of South America and across an endless blue ocean, up popped his adopted home.

When we arrive on the dark Molokai tarmac, the island’s parish priest, Father Bill Petrie, SSCC, greets us and reminds us of our intention. “Pilgrimages are filled with Godly events — but you have to look for them,” he says. “Hopefully you leave here transformed.”

The next morning, as we prepare to work with the local parishioners to repair and clean one of the four remaining Damien-built churches still in active use today, Father Petrie reiterates the point that we are being guided by Damien. “You have been invited by Father Damien,” he says. “You got an invitation, but to what? You’ll have to answer that yourself.”

The answer doesn’t come that first day as we work side by side with locals to cut down trees, weed gardens and prune bushes. Nor the second day as we hike the Halawa Valley, a lush epicenter for Hawaiian spiritual traditions, where nature and religion seamlessly intersect. The misty, mountainous path is strewn with ancient temples, rushing rivers and, at the end, a gushing waterfall. While we reflect out loud upon what this place could have meant to Damien and his followers, there’s still a disconnect between Damien and the students.

The invitation is still staring us in the face on Monday morning as we gaze down at the leprosy colony 2,000 feet below, impossibly far, in my estimation. As adrenaline and anxiety kick in, What am I doing here? plays over and over in my head.

The cliff, or in Hawaiian, the pali, is one of the largest in the world. There is no car access to that part of the island. Your options are to fly from Molokai to the bottom of the cliff or walk the three-mile path with its 26 switchbacks or sit astride a mule as it wobbles down the steep and muddy route.

When we think of pilgrimages, we think of walking, of ambling, of physical and spiritual journeying, so our group of 21 pilgrims plans to walk the trail. We’re determined to beat the mules and their inevitable droppings, so we’re there before the sun rises. It rained much of yesterday and the trail is muddy and shifty. We tighten our packs, full of enough vegetables, rice and peanut butter to sustain us for two days in the remote camp, before stepping onto the trail.

There are some rudimentary “stairs,” but it’s mostly just bits of stone and concrete scattered here and there to make sure the whole trail doesn’t slide out from under us. At least nowadays there is something of a worn and stable path. I picture Damien, a man made strong from years working his father’s farm, whacking his way through trees and vines, trying to clear a path on the cliff so he could regularly say Mass for the Catholics on topside Molokai. But I don’t let my mind wander long, the trail is wobbly and a misstep could mean a tumble down into the trees. We hike in a single-file line, heads down, planning our next step before we take it.

The careful walking embodies one of the themes we had selected for the trip: Be present where your feet are. In modern life I might be sitting in South Bend, emailing a colleague in New York, thinking about family in Chicago and planning when I’m going to fit a workout into my day, all in a single moment. My physical and mental presences rarely line up and are almost never concentrated on a single thing. Talking to the Notre Dame students, I realize their lives are even more overstuffed, overscheduled and overstimulated. For many, this trip is a realignment. They want to distance themselves from chaos and technology, and find time to concentrate on God.

“[At Notre Dame], Catholic faith is important, and we have that community of faith in the dorm Masses and Campus Ministry events, but we’re never really focused on our own journeys and being present to our thoughts and the thoughts of someone else in a faith experience,” says Laura Shute ’15. “The great thing about pilgrimage is that it strips away the distractions.”

This pilgrimage has attracted some atypical Campus Ministry participants. Sure, some theology majors and retreat leaders joined, but so did seniors looking for an alternative to a boozy spring break. One student was doing academic research on Brother Dutton. Others are pre-med and interested in a saint who cared for patients. We had Protestant and Muslim participants. We had an 18-year-old freshman and a 55-year-old priest. And we had 21 people all at different places in their faith journey. It made for compelling and occasionally strained discussions as we wound down each night. But one of the goals of these pilgrimages is to bring more students into Campus Ministry who may not wander in on their own, says John Paul Lichon ’06, ’09M.A., the assistant director of retreats, pilgrimages and spirituality.

“Every different place attracts a different type of student,” he says. When designing the Hawaii pilgrimage, he first thought of his father, who has had a devotion to Damien since Lichon’s childhood. Then he considered how the exotic location may open the scope of interested students.

To do a pilgrimage, and to do it well, context is key, says Father Jim King, CSC, ’81, ’87M.Div., ’07MNA, the former religious superior at Notre Dame. Before we came, we all attended a one-credit course that met once a week for half the semester and provided us material to read about Saint Damien, Kalaupapa and the laws that created the need for this center of isolation.

In those texts, we read that this peninsula was chosen because of the hike, the cliff. Authorities rightly assumed any leprosy patients would be too weak to make an uphill trek alive, so escape from the colony was impossible. Even while heading down, our group of able-bodied 20-somethings is huffing, and the three-mile hike still takes us an hour and a half. Thankfully, the hike is shaded by a canopy of trees and vines, keeping the rising sun off of our backs. But in time, the trail seems endless and we’re getting anxious, itchy.

Finally, a break in the trees, and all we can see is blue. The bluest water and the bluest skies I’ve ever seen. We cross a stone barrier onto an impeccable beach so pure, it’s as if human feet have never crossed it. And they don’t very often. The waves are rough and the undercurrents are worse. We’re warned that however tempting the cool water appears, the reality of its force should dissuade us from taking a dip. It’s hard not to notice the dichotomy of nature’s absolute beauty and terrible force, all in one place.

###

In 1865, people on the islands of Hawaii were terrified. Leprosy, likely brought over from the Asian islands and sometimes called Mai Pake, the Chinese sickness, was ravaging the native Hawaiian population. No one knew how to stop it or how it was transmitted. Treatments repeatedly failed. While 90 to 95 percent of the world has a natural immunity, Hawaiians were not part of that group. So, the king of the Hawaiian Islands, Kamehameha V, issued a decree of isolation. The islands’ board of health and police were authorized to arrest all they suspected of being leprous and to lock them in a leprosarium in Honolulu or to ship them to Kalaupapa.

The Hawaiian culture is rooted in the importance of community and ohana, family. So when people were being taken from their homes, the Hawaiians started to call the illness Ma’i Ho’oka’awale, the Separating Sickness. Sons and daughters were ripped from their parents. Husbands and wives were divided. In The Separating Sickness, a book of oral histories told by patients in Kalaupapa, many recalled the day they were taken from their families. One wrote:

“We had no choice coming here, you know. They took us away to Kalaupapa fast. I was only seven, and I did not know what was happening. They came to get me at school. I think the teacher reported me to the Board of Health. They used to get ten dollars for each leprosy person they reported.”

Meli Watanuki is one of the nine remaining patients at Kalaupapa. Even though she has been cured of leprosy for decades, she still refers to herself as a patient, as do the others. She grew up in American Samoa where, in 1952 as a teenager, she was diagnosed with leprosy. She was taken from her family and given treatment for several months, then was told she was cured and was released. Twelve years later, after she had moved to Honolulu, married and had a baby, she discovered a red spot on her knee that looked like a mosquito bite. When it didn’t go away, she went to the doctor and a biopsy was sent to Carville leprosarium in Louisiana for tests. The leprosy was back.

Watanuki was told she could be cared for in Honolulu and then could return to her family, but while she was gone her husband took their baby and fled the country. She was devastated and alone. So in 1969, the same year the isolation ban was lifted, she applied to come to live with other leprosy patients in Kalaupapa.

The petite woman with sun-tanned, leathery skin says she’s embarrassed about her scars and disfigurements, but they are barely noticeable. She has borne such despair in one lifetime, but Watanuki shrugs off any pity and insists she knew the saints of Molokai would care for her, through her battles with leprosy and, later, breast cancer. “I have strong faith in Mother Marianne,” she says confidently.

As we now know, leprosy is caused by a bacterium, mycobacterium leprae, a relative of the tuberculosis bacillus, and it causes lesions and sores, and such neurological damage as sensory loss and muscle weakness. Those with untreated leprosy are most recognizable by puffy facial sores, open wounds on the arms and legs, and disfigurements and amputations. Less noticeable but more severe symptoms can include kidney problems, bone absorption, nerve and vessel problems, blindness and a total loss of feeling to the extremities. In 1949, a sulfone drug was used to finally cure leprosy. Current treatment involves a cocktail of drugs that can render the disease noncontagious within a few weeks without the need for lifelong therapy. Still, according to the World Health Organization, a quarter of a million people are diagnosed with Hansen’s disease each year, while three million suffer its effects.

The disease has been around since the time of the Bible. The day we arrived in Kalaupapa, we celebrated Mass at Saint Philomena Church in Kalawao, the eastern portion of the peninsula that hosted those with leprosy in the early days before the site was moved west to avoid some of the rough weather. Before Mass, I noticed a smile creep over Father King’s face as he skimmed the readings for the day. In both, 2 Kings 5:1-15 and Luke 4:24-30, there is reference to a leprosy sufferer looking for healing. Coincidence, indeed.

In the reading in Kings, Naaman visits a prophet in the hope of being cured of leprosy. The prophet Elisha tells him to bathe in the Jordan seven times, but Naaman is angry, certain that such an act is not extraordinary enough to cure him. In the end, he relents and does the very ordinary act which does, in fact, heal him.

Ordinariness is worth reflecting on, says King in his homily. When we enter onto a pilgrimage, we’re looking for something huge, transformational. But instead, we visit churches. We reflect on the lives of saints and try to emulate their virtues. We pray for their inspiration to touch our lives. We pull weeds and clean out cobwebs. It’s all ordinary.

“Father Damien didn’t become a saint because he did something extraordinary. He wasn’t a homilist that people sought out. He wasn’t a remarkably talented carpenter,” King says. “He was just ordinary.”

But he was there for a population who needed him, who needed hope, who needed dignity and compassion. He was able to provide unending support and love, even when the patients disobeyed him and sinned and rejected him. He didn’t cure people or release them from their captivity; he was just present with them and for them. He became one of them.

So, King asks, why shouldn’t we be content with ordinary?

The students shift in their seats, seats that once held rows of leprosy patients. Since these students entered Notre Dame they’ve been told they have the potential to save the world, to incite change, to make a difference. Later, some of them admit that they would feel guilty, feel like they’re letting Notre Dame down, by settling for ordinary. But King’s homily lets them off the hook. It reminds them that greatness is not their call as Christians. As Christians, they’re called to love one another, to make each other’s lives easier, to give of themselves and their possessions. There is no mention of success or salaries or being busy in our universal vocation.

For me and others, those few moments sitting in a church built by Saint Damien are the most influential of the whole trip. When we return to South Bend days later, many of the students write their final projects about that homily, about commitment to ordinariness. They also talk about how witnessing the life of Damien was witnessing not the life of a saint but the life of a human like the rest of us.

In our readings, we saw Damien was not without sin. He was contrary, controlling, occasionally insensitive and, at times, importunate.

Notre Dame Archives holds a series of letters written by Damien. In one, he asks Father Daniel Hudson, CSC, then head of Ave Maria Press, to raise money for two tabernacles for the churches down in Kalawao. In the next letter, he asks for brochures. Then six candlesticks. A few months later, he asks for books and money. The “please send” list grows exhaustive.

Gavin Dawes’ book Holy Man: Father Damien of Molokai gives an account of young Damien’s jealousy when his elder brother, also a priest, is scheduled to leave for Hawaii. When Pamphile catches typhus and cannot go, Damien eagerly campaigns for his slot and then waves the letter in Pamphile’s face once it is granted.

This type of story, one not scrubbed clean by history, is what attracted Laura Shute to the study of modern saints. “It’s cool that Damien isn’t Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. She’s quiet and perfect and almost seems like the unattainable saint. Damien is throwing logs around Kalawao and yelling at people and making fun of his brother. It made you realize sainthood is more attainable,” she says. “It was interesting to see saints are imperfect.”

Lichon agrees. He says that while Damien’s life — moving across the world, serving a banished community, risking his life — seems so different than our own, Damien’s imperfection and normality remind us of his humanity and of our ability to become saints despite our sins.

###

Back in Kalaupapa, we can’t help but be confronted with the mundane over and over again. Kalaupapa is dingy. The houses and buildings are barely shacks. Only a handful of other buildings exist: a post office, a store the size of a dorm room that preorders only the essentials for residents, a small bookshop that one of the patients operates, a clinic and a few churches. The residents get a shipment of items such as clothes, cars and appliances only once a year. Life here is simple beyond our comprehension.

It’s also eerie. As the sun sets, we’re left in utter darkness and silence. But something within each of us is not quiet. Maybe it’s the souls of the 8,000 people buried beneath us. Maybe it’s a comprehension of the reality of all we studied, of seeing the effects of the horrific disease, of hearing testimonies of how it destroyed people and families and created this place. To shake the spooky feeling, we curl into cots under sheets that don’t provide warmth and are forced to confront the fact that Damien insisted on sleeping on the floor for many of his years here.

Damien may have been forgotten along with this dwindling place, had it not been for Joseph Dutton, says Lilia Draime ’15. Dutton, a lay person who worked alongside Damien for three years, was responsible for preserving Damien’s possessions and for publicizing his good works even long after his death. It is Dutton, she theorizes, who made Damien’s canonization possible.

Draime stumbled upon Dutton’s papers by accident, or, as she says, he chose her. He was known to have an index with 4,000 contacts, 200 of which he kept up with regularly. The largest collection of those letters resides at Notre Dame but amounts to fewer than three boxes. With a shortage of information and possessions that have been lost over time, little extensive research has been done on Dutton’s life, making it difficult to canonize him with his contemporaries, Damien and Marianne.

Last year, The Committee for the Cause of Joseph Dutton for Canonization was formed. Draime’s senior thesis on the life of Dutton, a veteran, an alcoholic, a Catholic convert and a devoted follower of Damien, will lay the framework to build Dutton’s case to the Vatican. But as I fire questions at her about Dutton, for many she just smiles and shrugs with a polite, “We don’t know.” But her hope is that Dutton is not lost in anonymity.

His former home also is at risk of being forgotten. Once the remaining nine aging patients are gone, the future of Kalaupapa is as rocky as its shores.

There are whispers of it becoming a resort, of modernizing this little part of Molokai to stimulate the economy here. Others say the National Parks will inherit it. The patients want it to become a museum or a memorial to all those lost here. And nature is trying to reclaim its rightful place: Stop signs get tangled in vines, tree trunks swallow stone tombs and natural overgrowth is taking over the man-made.

The space could also become a pilgrimage destination. Right now, its infrastructure is minimal at best and its pilgrims few. As King notes, it is no Rome, no Lourdes. Tours are short and informal. Even our overnight stay is abnormal — guests aren’t typically welcome and are allowed to stay only if sponsored by a patient.

More important than the physical space, though, is what we are reminded of when we are there. People were pushed aside, considered worthless. We could point a finger and ask, “How could they have been so insensitive and cruel?” Or, as pilgrims and as Christians, we could consider, Who are the lepers in our own lives? Are there people you cast out? People who wear on your patience? How can we be like Damien and embrace and serve them?

Anyone come to mind? They sure do in my life.

Before we began the trek back up the cliff, back to topside Molokai, back to the mainland, back to South Bend, back to our normal lives, we took a half hour of silence. We sat on that beautifully violent beach and prayed and contemplated and prepared.

With my back on some stones and my feet getting tickled by the ebb and flow of the water’s tide, I thought about Kalaupapa, about Damien, about the students around me and about ordinariness.

Perhaps we had all hoped and prayed for spiritual revelation. After all, in these few miles, two saints were formed. Maybe we hoped we would feel that, be lifted by it, see a spiritual journey crest for a moment. It didn’t happen that way. It was fascinating. The stories were gripping. The place was heavenly and hellish all at once. It was like nothing most of us have ever seen, but the feeling was missing.

Instead, we’ve returned to ordinary life. Despite spending a week thinking about sainthood and compassion, thinking how we can be better, do better, love better, I think we’d all admit there are days we don’t. For most of us, there was no moment of epiphany, no moment of extraordinary.

But King has said that discernment isn’t logical, and wisdom doesn’t come when you shout for it. All this trip was meant to do, he says, was plant a seed, nourish its growth and hope that someday, in one of these lives, someone is changed.

Tara Hunt is a former associate editor of this magazine.