When I was 6 or 7 years old, I was usually sent to bed before I preferred and, more times than not, before I was sleepy. To encourage sleep, my parents didn’t allow me to take any toys to bed, and I wasn’t much of a stuffed-animal lover. But I wrangled out of these limitations because I had an old Dutch Masters cigar box, complete, on the inside cover, with Rembrandt’s group portrait of De Staalmeesters and their funny-looking Dutch cavalier hats. In this slightly frayed cardboard coffer, I hid my collection of the stray cufflinks and tie clasps that my older brothers had passed on. I also had a stained clip-on bowtie that I had filched from a bedroom waste basket.

This cache of trinkets became denizens of my pillow. They were my early-to-bed play chums, citizens of a place I called Longbed Hill. Matched cufflinks were married couples; matching tie clasps were their children. Unmatched tie clips were orphans, and unmatched cufflinks were the children’s teachers. The bowtie was the school bus, and it was yellow. Each of the parents had a name, as did all the teachers and the children. I remember only one of those names today: Seth, which is the same name of the wagon master played by Ward Bond on TV’s Wagon Train. These toys had arguments and disagreements and bad grades and spelling bee awards. Some children, the tie clasps that opened and shut like a crocodile’s mouth, were mean. The nicer children were slip-on clips, smooth and without teeth.

Longbed Hill was a little world to a little boy. And when I awoke in the morning, I gathered up all the pieces and returned them to their Rembrandt friends, who would gaze down inside the dark box on the displaced natives of my pillow town. I knew they were trinkets, and yet I knew they had personalities. Even without the right words, I knew these locals were not real; still, I felt their reality, their joys and their pains in the little adventures that occurred as I slipped into sleep and, later, as I slipped them back into the box.

I don’t know where they are now, but the old, nostalgic adult in me wishes I could gaze upon that cigar box of imaginary life. It’s a good question: When did the citizens of Longbed Hill become irrelevant to their caretaker and chum? When did I put the box away for the last time? Memory gives me no answer, but memory serves very well to remind me of those early-to-bed playthings. I think perhaps that those imaginings on Longbed Hill and my outgrowing of them are the beginning of a pattern in my life.

Why do toys never die? Obviously because they were never alive. But this easy response is only literally true.

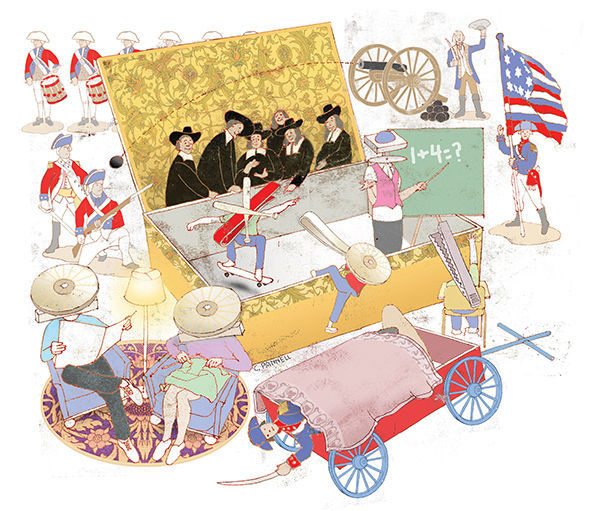

When I was in third grade, my best friend was Charlie Drum. After Christmas vacation, I was telling him about the soldiers I had received from Santa (Charlie was already a nonbeliever), and he was just as excited about them as I was. The soldiers were plastic pieces poised for combat or posed in march step. They came in two colors: blue for the Revolutionary American, red for the British. I started bringing the soldiers to school in the lunch pouch of my book bag, and after school — since I was now old enough to walk home without older sibling supervision — Charlie and I went to his house and had our little war upon the linoleum in his parents’ kitchen. We reversed British and American roles from day to day. He had other items we included: toy wagons and trees and cannons from an old Civil War model that someone gave him. Beside each cannon was an immovable pyramid of cannonballs. We set up our phalanxes (a word we didn’t know) and rolled marbles at our enemies.

Charlie gave me an incredible revelation one day when his general was knocked over by one of my marbles. He placed the general in a wagon and covered him with a wash cloth and lined his men up for a funeral. He hummed “Taps” while I watched in awe.

Thereafter, whenever a general got knocked over, the battle stopped and we had a funeral. In the spring, when we could play outside, we began burying our dead, and not just the generals. We’d dig holes in the hard dirt, bury the dead heroes and place shortened Popsicle sticks at their heads. The next time we played, we easily exhumed the fallen soldiers from their graves and began again. Sometimes a rain storm would wash away some of the wooden tombstones, and we’d become archaeologists of our own past. We weren’t always successful, and our cache of soldiers lessened over time. I suspect that in Charlie’s old backyard, some curious child will discover an odd burial site of blue and red toy soldiers. And after the child washes the discoveries, he or she will be pleased.

Remembering both the Longbed citizens and the soldiers, I see a change. The pattern of play is similar, based as it is in the imagination, but there are differences. Longbed Hill was a secret I divulged to no one. Longbed Hill had individuals with names and stories; its people talked to each other. The plastic soldiers were nameless groups working for nameless generals. Nevertheless, there was a more poignant reality to the soldiers. Funerals and burials never happened in Longbed Hill. Problems, disputes, troubles and loneliness — yes. But death? Death was unheard of. Charlie’s presence also involved a change; playing now was an act of partnership. We shared our imagination without embarrassment or fear of each other.

But it was also public play. His sisters and his parents passed through our battle sites. They heard our explosions and our hummed elegies. They saw our funeral parades and our battle strategies. They heard the sounds of our naïve explosions: Doosh! Charlie’s sisters — all older than he — took great amusement in our play. “Bowling with soldiers,” one of them commented because of the marbles. We learned, therefore, to whisper at times (“The Redcoats are coming!”) and to hide some of our methods.

When I combine our battle-and-funeral play and my own private play with cufflinks and trinkets, I see the pattern of my imaginary life taking another variation. I suspect the variation has to do with growing up. Phyllis McGinley, in The Most Wonderful Doll in the World, a charming albeit didactic book, makes clear that no toy can ever match what a child makes of it; and besides, she says, children necessarily outgrow their childhood imaginings. She may be right, but the patterns of my life lead me to question her conclusion.

Kids get over their toys; they move on, and what was once central to them now moves to the outer edges of importance, and then it has no importance at all. How could I have lost track of my cigar box? The specific playthings lose importance, but not the act of playing. Toy soldiers are replaced by miniature electric trains or sailboats in a pond. My colleagues at university have playthings: one has miniature figures of famous baseball players; another has figures of characters from horror movies and X-Men comics; a Victorian specialist is very proud of her Jane Austen doll. I’m sure my colleagues don’t “play” with these figures as Charlie and I played with our soldiers, but their presence on the windowsills and bookshelves suggests to me that the enjoyment of toys never really ends.

Yet even with the diminishing importance of specific toys as we grow older, our playthings teach another lesson. Toys never die. They can be abandoned or boxed up and sent to a shelter for the homeless. They can be destroyed: plastic soldiers can be melted, iron cannons can rust; wooden dolls and puppets can burn — but the toys never die. And at the shelter, when the box is opened, some child will find a doll that suits him or her just fine. Another child will be smitten by a green, plastic brontosaurus.

Why do toys never die? Obviously because they were never alive. But this easy response is only literally true. A puppet may spend a decade hidden in an attic or on a shelf in the garage, but once it is rediscovered by a child, it is alive.

During a recent visit, my 3-year-old granddaughter was being given a bath by her mother. My wife went to the old chest of toys in the basement to retrieve some things our kids had used. One toy specifically stands out. It is a plastic boat of faded shades of red, white and blue. A figure resembling a sailor, with wide brown eyes and a blue, round sailor’s cap, fits snugly in the boat’s hollowed center. When my kids were bathed by my wife or me, we always gave them some playtime in the tub. The favorite toy for each of my kids was this unsinkable boat and sailor. I christened the sailor Palinurus, after the drowned man in Virgil’s Aeneid who keeps popping up wherever Aeneas goes. The name stuck, but the children’s interest waned mostly because they outgrew playtime in the bath. Now suddenly our granddaughter was saying “Palinurus” and enjoying sinking him and watching him pop right up above the sudsy surface.

I believe that the child’s imagination lives on in the adult, diluted and dulled perhaps, but alive. I see it in the eyes of retirees who taste a soup and recall some pleasure from the past. It is not simply nostalgia that draws their smile; it’s the imaginative reliving of something from long ago — a task accomplished solely by imaginative remembrance. Parents who make up songs for their toddlers are engaging their childhood imagination. And practically all artists, poets, novelists, engineers and architects link their adult achievements to their childhood play.

To say that toys never die may simply be another way of saying the imagination never dies. As long as there is an imaginative mind nearby, an old toy becomes young again, new to the next player.

Still, I prefer the idea that toys have an interior life of their own. My tie clasps sometimes got angry; my cufflinks on Longbed Hill felt the joy of winning a spelling bee. Charlie Drum and I watched our toy soldiers mourn the loss of their generals (until we played again the next time). It’s a wild paradox, seeing life in lifeless things, but such antinomies are profound and ultimately humanizing.

These effects are not quantifiable, of course, but I believe they can be substantiated with recourse to a certain kind of literature, the stories of sentient toys, which are usually categorized as children’s or young adult literature. In The Mouse and His Child, Russell Hoban introduces us to a panoply of toys that think and feel. One of the delightful aesthetic premises of the genre is that each toy lives with its own physical limitations. So a wind-up toy elephant can flee only so long as her springs are unwinding; with the springs unwound, the elephant stops dead in her tracks and bemoans her own fate, which seems to worsen over time.

Hoban lists the tribulations of toys by showing us the experience of the elephant as she gets her last glimpse of the toy store in which she was so happy:

She who had thought of herself as a lady of property, secure in her high place — she had been sold like any common toy, while the gentlemen and ladies in the doll house never so much as looked up from their teacups. The house itself, her house, as she had always believed, had been cut off abruptly as the tissue paper closed over her head, and thus her world departed, and reality was thrust upon her.

At the grand house to which she is taken, this elephant toy “endured what toys endure.”

She had been smeared with jam and worried by the dog, she had been sat upon, and she had been dropped, had been shot at by toy cannons, and had been left out in the rain till her works had rusted fast and she was thrown away. Still she endured, and deep within her tin there blazed a spirit that would not be quenched.

The tin elephant is not the book’s main character, but the roster of wrongs done to her is the given of every toy’s career. The main characters, the windup mouse and his child, implicitly have gone through similar misuses, and they find themselves part of a junk heap. If we add to this list the suffering the mouse and his child experience in the rest of the story, their quest to find a place to live as liberated beings becomes heroic. But the elephant reminds us that, even without epic battles and forays into macabre social environments, every toy has an almost thankless life — which makes me want to lament my callousness in closeting my trinkets in the dark interior of a cigar box or crowding my soldiers in a lunch pouch.

Readers of Hoban’s book and others of the genre cannot respond without empathy because in these works, the toys — Edward Tulane and the velveteen rabbit, for example, and, of course, Buzz and Woody from the Toy Story films — are quintessential instances of the downtrodden. The books require their readers to explore in themselves the most foreign of viewpoints. What is it like to be a wind-up toy? How does it feel to be a porcelain doll with a cracked skull?

Which is what I think happens when we accept as true the fiction that our toys have lives of their own. Living with such a paradox opens up new vistas for the imagination, sights perhaps that don’t reveal themselves to the mind until much later. Some new views verge on the profound: Playing with the red and blue soldiers makes us wonder what the point of human life is when we lay waste to so much of it in wars where dead men and women do not rise to make war another day.

When Ward Bond died in 1960, I was 8 years old, and I cried intermittently for days. He was my first death; the red and blue generals were painless dress rehearsals. But without those practice moments, the enormity and the triviality of the wagon master’s death might have forever escaped me, even though as an 8-year-old I hadn’t the words to express my grief: I cried, and he was immediately replaced by another actor, and the show went on. And therein lies the significant pattern of my life: the incapacity to articulate the meaning of things until they are irretrievably gone.

Patrick McGuire is a member of the English Department of the University of Wisconsin — Parkside. He is the author of the poetic sequence Meditations on the Mysteries of the Holy Rosary; his blog is McGuireHimself.com. He is married to Chicago theater director Anna Antaramian.