Editor’s note: In commemoration of the anniversary of the death of Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, on February 26, 2015, Notre Dame Magazine is publishing selections from our Hesburgh Special Edition here at magazine.nd.edu. We will publish one piece per weekday through Wednesday, March 2. Print copies of the special edition are available; please visit our store for ordering information.

Tomorrow: The Right Side of the Road by Kerry Temple ’74.

After retiring from the Notre Dame presidency in 1987, Father Hesburgh was fond of sharing — and living — a personal credo in facing one’s later years: “Do as much as you can, as well as you can, as long as you can, and don’t complain about the things you can no longer do.”

Wisely commonsensical, plain-spoken and direct, Hesburgh’s words and his similar versions defined his actions during a post-presidential afterlife as eventful, in its way, as his earlier years. Abiding continuities — priestly service, devotion to Notre Dame, working for international peace and justice, and trying to strengthen American higher education — occupied his days and created a crowded calendar. He occasionally referred to himself as “an old goat” in conversation, but his schedule would tire someone half his age.

Special Masses, formal meetings, arranged talks, office appointments, off-campus trips, and an endless succession of media interviews and dinners — all competed for Hesburgh’s time and challenged any concept of rest-on-your-oars, conventional retirement. Honors and awards also came with such frequency that during much of his twilight he remained quite visible, never far from the limelight. Though always referred to as “Father,” age brought new self-realization. “I enjoy the role of being everybody’s grandfather,” he once said with a smile.

When Hesburgh left the president’s office in the Main Building, he wanted his successor, Rev. Edward A. Malloy, CSC, to have a clear field to develop his own administration. After hearing jibes for all the traveling he’d done the preceding 35 years, Hesburgh still thought it best to take to the road — for pleasure this time — and remain absent from Notre Dame for a full year.

Accompanied by Rev. Edmund P. Joyce, CSC, his executive vice president throughout the 35 years and close friend, the two priests set off first in a motor home to explore the western United States, later taking to the air and sea to visit places around the world. No longer obliged to get somewhere for a scheduled event or meeting, they could wander as tourists, enjoying the sites.

- More from the Father Hesburgh Special Edition

- The Maker of Notre Dame

- The Strength of Leadership

- The Endless Conversation

- The Right Side of the Road

Serving several months as chaplains on the Queen Elizabeth II during a 1988 world cruise, Hesburgh and Joyce spent their sabbatical year free of any University worries and responsibilities. They got away, created breathing room for the new administration and assumed a different pace. As Hesburgh later said, “Retirement had begun with a bang, not a whimper.”

Hesburgh recounted the adventures (and occasional misadventures) of the months removed from Notre Dame in his diary-based narrative, Travels with Ted & Ned, published by Doubleday in 1992. Two years earlier, Doubleday had released Hesburgh’s autobiography, God, Country, Notre Dame, a critically admired bestseller that in hardcover and paperback editions circulated in more than 500,000 copies. In 1994, Hesburgh assembled, edited and introduced The Challenge and Promise of a Catholic University, a wide-ranging series of essays for the Notre Dame Press.

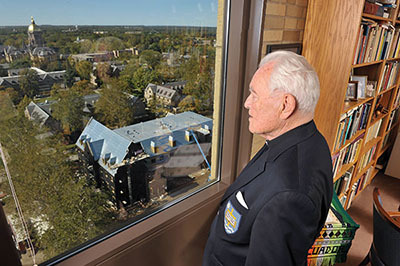

That book projects took up so much of his early retirement years seemed only natural. Hesburgh then worked in a book-lined office on the 13th floor of the University library that since 1987 bore his name and to which he had given his prized collection of author-inscribed volumes. The original benefaction in 1993 of 1,200 autographed copies (from world notables in politics, science, religion, business and the arts) has grown to 1,600 titles during subsequent years. A lifelong lover of books was leaving behind for others those with special meaning for him.

After Notre Dame’s Commencement in 2006, the author Harper Lee, an honorary degree recipient that year, sent a copy of her acclaimed novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, to a figure she’d long admired and finally had a chance to meet. “To Father Hesburgh in awe,” she wrote above her distinctive signature.

Forever learning

Notwithstanding his publishing productivity (three volumes between 1990 and 1994) and occasional op-ed columns for The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and other publications through the first decade of the 21st century, Hesburgh never cut himself off from the life of the University and the outer world for solitary, bookish pursuits. As happened throughout his presidency, invitations to serve on boards and commissions or to conduct special projects arrived with regularity.

For example, in 1989, he was named co-chair of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics, work that encompassed the better part of a decade. A year later, he was elected to a six-year term on Harvard University’s Board of Overseers. The first priest on Harvard’s Board, he subsequently was chosen president of the Overseers in both 1994 and 1995. In 1991, President George H.W. Bush nominated Hesburgh to serve on the board of directors of the U. S. Institute of Peace, a post he held until 1999. Other, less time-consuming appointments came along, and he’d fit them into his busy, “unretiring” schedule.

Within Notre Dame, three programs he was instrumental in launching — the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, the Kellogg Institute for International Studies, and the Center for Civil and Human Rights — continued to receive special attention. Hesburgh made a point of participating in their meetings, conferences and other activities, not only to show his support but also to stay up-to-date in the thinking and policy initiatives related to areas he considered critically important.

In fact, a unifying lesson of Hesburgh’s post-presidency is the enduring value of sustained, self-directed continuing education. His constant openness to new knowledge helped him develop a more rounded and deeper understanding of America and the world.

“You learn a great deal because you’ve got to get down to primary sources,” he told me, noting the study time required when he had served on the National Science Board, the Commission on Civil Rights, the International Atomic Energy Agency and later on the Knight Commission and the U.S. Institute of Peace. Quick to master complex data and multivolume reports, Hesburgh always probed the moral dimension of a subject. Ethical and spiritual concerns were never very far from the scientific, social or academic matters that engaged him.

Looking back in 2005 during an extended interview about his retirement years, he talked first about his appointment on the board of the U.S. Institute of Peace. Mentioning trips to Kosovo, the Middle East and elsewhere, he said, “Every time there was a crisis we got into it.”

Hesburgh brought to his work with that institute his own, distinct perspective. “I think the methods of peace are multitudinous,” he noted, “but I like mediation where you can sit down with the two aggrieved parties and somehow work it out between them. It reminds me a great deal of what I’ve done as a priest in trying to fix up marriages that are going sour. You’ve got to understand both sides, and you have to be fair with both sides — but you need to be firm about what steps are needed to achieve peace in a family or a nation or in the world.”

His own efforts as priest-peacemaker help to explain why he devoted so much of himself to seeing peace studies flourish at Notre Dame. Pointing out that “we are the largest endowed peace endeavor in the whole world,” he enjoyed telling how the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies came into being in 1986 and ultimately received nearly $70 million from Joan Kroc.

“It all started with a talk I didn’t want to give in San Diego, because I was on the alumni circuit, giving talks every night,” he recalled. Joan Kroc, widow of McDonald’s Corp. founder Ray Kroc, happened to be in the audience and became interested in supporting scholarly work focusing on conflict resolution. Initial gifts during Hesburgh’s final years as president continued after he left office, with Mrs. Kroc leaving the Institute $50 million when she died in 2003.

Sports reform

Although Hesburgh called his service on the Harvard Overseers “a wonderful experience” because it provided him “an inside track on everything going on at Harvard,” he found co-chairing the Knight Commission demanding and, at times, depressing. Investigations by the commission revealed the stark underside of amateur sports being played on campuses across America. In Hesburgh’s words, “We developed a picture of intercollegiate athletics that would make you want to vomit. It was out of control and getting worse.”

Formed two years after he retired, the commission singled out the seeking and spending of money as the overriding problem. Selling tickets for games and post-season contests — along with lucrative television contracts — contributed to rule-challenging searches for athletes, the so-called “talent,” in the revenue-producing sports of football and basketball. Some of the prized recruits cared little about receiving an education, a situation more than a few schools were willing to abet by looking the other way or designing less than rigorous curricula. “We turned up one guy who couldn’t read or write,” Hesburgh remembered, “and he was in a university.”

In particular, according to Hesburgh, minority athletes were vulnerable to exploitation: “They were simply used for four years and then thrown out on the garbage heap, not having any degree or any skill because they were fed kindergarten courses during what was supposed to be a university experience. They were not educated at all. They were just used.”

‘I was filled with a conviction that I wasn’t being ordained for myself, that I was an instrument in the hands of God. I wasn’t to think that I simply belonged to Catholics; I belonged to every human being.’

Hesburgh approached his work on the Knight Commission as he had so many earlier assignments. Moral concern merged with a sense of injustice that cried out for change. In a widely quoted statement early in the commission’s deliberation, Hesburgh put the matter bluntly: “If some schools don’t want to join this reform effort, they can form their own outlaw league for illiterate players.”

By the time Hesburgh concluded his service on the Knight Commission, the NCAA, which governs intercollegiate athletics, had formally adopted about 90 percent of the commission’s proposals for correction and improvement. Hesburgh, though, wasn’t completely satisfied, because he had pushed for a particular change that hadn’t been implemented.

“I always held for one academic remedy,” he recalled. “My remedy was that if you didn’t graduate at least half of your athletes in football and basketball, you would be disqualified from winning the championship in your conference or playing in post-season games. That one move, I thought, would really take care of the problem in a hurry.”

Trying to reform collegiate sports provoked criticism of the Knight Commission, often directed personally at Hesburgh. “The super jocks thought we were out of our minds,” he said later. But being on the receiving end of disapproval was nothing new for someone who’d spent much of his lifetime trying to solve thorny problems in the bright glare of media scrutiny.

The Clinton years

During his retirement years, one particular activity prompted bitter opposition, especially among more politically partisan Notre Dame alumni. In 1994, Hesburgh was named co-chair of what was called a “Presidential Legal Expense Trust,” established to raise money for the personal legal expenses of Bill and Hillary Clinton related to pre-White House business and conduct. At the time, the Clintons were under investigation for a failed real estate investment in Arkansas, known as Whitewater, and the president was defending himself against a sexual harassment lawsuit by a former Arkansas state employee, Paula Corbin Jones.

The other co-chair of the trust was former U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, and trustees included John Brademas, long-time member of the House of Representatives from Indiana and president emeritus of New York University; Michael Sovern, Columbia University’s president emeritus; and Elliot Richardson, a cabinet member in several Republican administrations.

Despite the distinguished participants and the strict restrictions on gifts (a maximum of $1,000 per year “only from individual citizens other than federal government employees, not from corporations, labor unions, partnerships, political action committees or other entities”), the trust was called — in the headline of one New York Times editorial — “The Tainted Defense Fund,” and a federal suit, filed in Washington’s U.S. District Court, sought to shut it down.

More controversial than successful, the trust ended its work after three-and-a-half years, with the Clintons still owing more than $3 million in legal expenses. In the last year, 1997, legal and administrative costs to keep the trust operating exceeded donations it received.

Throughout the experience, Hesburgh considered the higher purpose of his involvement, frequently commenting, “I agreed to do this for the presidency, not necessarily for this president. I would have done it for any president.” In his view, it seemed “unfair for a sitting president” to worry about enormous legal fees “while he had more important national and international concerns to face.”

In retrospect, almost a decade after the trust ended, Hesburgh summed up the endeavor within a larger context. “I would say the whole thing was one of the most unproductive things I was ever involved in,” he said. “Holding out a hand to a guy when he’s down didn’t seem to me to be a terrible thing to do, although those things tend to break down Democratic and Republican. Republicans hate you, and Democrats love you. But I was always nonpolitical. I never endorsed anybody. There was some criticism, but I just took it as a tempest in a teapot.”

Although Hesburgh saw his involvement in institutional terms — helping the presidency — Bill Clinton, as a person, impressed him, particularly at their first meeting on June 24, 1993. Hesburgh was in Washington on business for the U.S. Institute of Peace when he received a call summoning him immediately to the White House. Ushered into the Oval Office, Hesburgh recalled being asked: “Is it true that you were ordained a priest 50 years ago today?” After the priest replied yes, Clinton said: “Then I think it is proper you should be in this house and in this office so I can congratulate you on what you have done for your Church as well as what you have done for your country.”

Seven years later, on July 13, 2000, Hesburgh told this story in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol with the president and leaders of the House and Senate present as he received the Congressional Gold Medal, the first ever conferred on someone in advanced education. The Gold Medal is the highest award Congress can bestow, and recipients include George Washington, Winston Churchill, Mother Teresa and Nelson Mandela.

‘The true antidote to the public’s view that colleges are simply ivory towers of intellectual dilettantism is engagement with important public issues — however difficult and thorny those issues may be.’

In his remarks, Clinton, who interrupted Middle East peace talks at Camp David to present the medal, turned to Hesburgh and said, “I would say that the most important thing about you and the greatest honor you will ever wear around your neck is the collar you have worn for 57 years.”

Later in the proceedings, Hesburgh echoed the president’s words. “You might say this is the happiest day of my life, but it really isn’t. The happiest day of my life was when I was ordained a Catholic priest, lying stretched out on my face in the sanctuary of Sacred Heart Church at Notre Dame. I was filled with the Holy Spirit, who has fortunately stayed with me all these 57 years. I was filled with a conviction that I wasn’t being ordained for myself, that I was an instrument in the hands of God. I wasn’t to think that I simply belonged to Catholics; I belonged to every human being.”

Awards aplenty

As priestly instrument, Hesburgh earned widespread recognition during the years he served as Notre Dame’s president — in 1964 President Lyndon Johnson awarded him the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor — and subsequently throughout his retirement years. In 1998, for instance, Indiana Governor Frank O’Bannon named him one of five “Hoosier Millennium Treasures.” In 2004, the NCAA bestowed on him the inaugural Gerald Ford Award for his decades of leadership in intercollegiate athletics, and the following year the College Sports Information Directors of America gave him the Dick Enberg Award for his commitment to the values of education and academics within collegiate sports. In 2006, Indiana’s highest tribute, the Sachem Award, was bestowed on him, and, in 2010, Catholic Charities USA announced that Hesburgh was the recipient of a specially commissioned Centennial Medal for his efforts to reduce poverty.

Special honors came with such constancy that the reception area and sitting room of his library office took on an award motif, with an etched vase or bowl sitting chock-a-block next to an engraved sculpture or medallion.

Most remarkably, by the time of his death, he had received 150 honorary degrees, the most ever awarded to one person. Though pleased with the far-flung colleague-sanctioned acclaim within higher education, Hesburgh tried to keep his feat in perspective. Each certificate and doctoral hood was given to the Notre Dame Archives. “After I kick off,” he told a reporter in 2002, “they might display them some place. But that’s only because I wouldn’t be around to stop them.”

In addition to receiving awards, honors were named for him. The Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities created the Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, Award for outstanding contributions to Catholic education. TIAA-CREF (the retirement and investment firm established for educators) instituted the Theodore M. Hesburgh Award for Leadership Excellence, to recognize distinction in faculty development that enhances undergraduate teaching.

Although recognition tended to look backward to prior achievements, Hesburgh in retirement focused on the present and the future. A month shy of turning 88 in 2005, he told a visitor, “I have a full schedule every day and very little time off. I’d rather have it that way.”

In 2007, he participated in a 90th birthday celebration in Washington, which featured a visit to the White House and a ceremony at the Smithsonian Institution. At the event, attended by government leaders and other public figures, a photograph of him hand-in-hand and shoulder-to-shoulder with civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was unveiled and added to the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

On St. Patrick’s Day in 2012, Father Hesburgh was granted Irish citizenship in a ceremony that brought Enda Kenny, the Taoiseach (or prime minister) of Ireland to Notre Dame. In receiving his new Irish passport, Hesburgh talked about using it for another trans-Atlantic trip to visit the birthplace of his grandfather, Martin Murphy, who immigrated to America in 1857.

An intrepid traveler for over eight decades — in 1993 he remarked “I’ve been in 160 countries and around the world many times” — Hesburgh reached the point where failing eyesight caused by macular degeneration prevented him from reading an airplane ticket or the room number at a hotel. In rare instances, he’d make a trip off-campus, but private transportation and someone to help serve as guide became necessary.

Finding light in darkness

For an avid reader and constant writer, macular degeneration could be a cruel sentence to years of darkness. Hesburgh, however, adapted to the challenge, brushing it off as the “nonsense that happens” in a long life. In place of reading, he listened to audio books provided by the Library of Congress— as many as 30 a month. To help him keep up with current affairs, students stopped by his office to read The New York Times and other publications with him.

“Once your eyes go, you can’t drive, you can’t read, you can’t write,” he said. “I can’t even write a few notes down for a talk. Everything has to come out of your head and your memory.”

Hesburgh recalled the sense of trepidation he felt before delivering the eulogy for Father Joyce before a crowded Basilica of the Sacred Heart on May 5, 2004. “I remember when Father Ned died, I just thought about it for two days. There were a million thoughts, of course, because we’d been together so long. Climbing up the steps of the pulpit, I said, ‘Lord, I don’t know what I’m going to say, but I hope you’ll keep me down below 15 minutes.’ I just started out, and the Holy Spirit is a fine inspiration on all these things. My first prayer in the morning and the last one at night is ‘Come, Holy Spirit.’”

For listeners in the congregation and readers of the published version, Hesburgh’s remarks were among the most memorable he ever uttered. A colleague, confidant and friend was movingly brought to life — and thanked — at the funeral Mass.

Near the end, Hesburgh said, “I know we’re going to miss you, Ned, but we all go when the time comes and your time has come. I guess the best I can say is thanks, Ned, for those long days of caring, those long nights of work in the cause of Our Lady’s school, to make it better and more worthy of her.

“Thanks for all those prayers we needed, when we needed them very much. Thanks for all the wisdom that kept me from making a lot of silly mistakes at times. And thanks just for being a brother to your brothers [in Holy Cross], being a friend to all of us, being a willing and dedicated priest, ready to act like a priest when I needed it, and God knows I needed it a good deal.

“I guess all we can say is, Ned, we’ll be seeing you. I truly believe that. There will be more days when we can get around and talk about the glories of this wonderful place and all the wonderful people. There will be days ahead when we can look back and thank God we got through without too many scrapes and bruises. But especially, I think, we’ll look back with great gratitude for that wonderful grace Jesus gave us both in making us priests.”

Hesburgh’s inability to read and write necessitated changes in how he communicated, but he was willing to try other means and modern media to convey his thoughts to a large audience. In 2004, the Notre Dame Alumni Association created a videotape-DVD, A Man for All Generations: Life’s Lessons from Fr. Ted Hesburgh, C.S.C., while Family Theater Productions came out with God, Country, Notre Dame: The Story of Father Ted Hesburgh C.S.C.

Both productions featured the still-telegenic Hesburgh reflecting on subjects he felt deeply about and on his own experiences. Always articulate, often eloquent, he talked without notes or preparation about the virtues of a well-lived life, the importance of prayer and the need for facing death with courage. Inspirational homilies of hope, the vivid phrasing and reassuring voice made for compelling television.

In the Alumni Association production, Hesburgh was the sole speaker; in the other, several friends and admirers (including three former presidents: Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush) offered statements about Hesburgh and his public service to supplement the priest’s reminiscences and recollections.

As the problem with his vision got worse and constant travel became impossible, Hesburgh decided to decline any assignments away from Notre Dame. The last major appointment he accepted was one made by President George W. Bush in 2001 to serve on the Commission on Presidential Scholars. It was the 16th time a president had called on Hesburgh to serve.

Campus connection

Earlier in 2001, Hesburgh published one of his last major statements in The Chronicle of Higher Education. Shaped from a speech he delivered at Notre Dame, the essay was, in its way, a lament that asked a pointed question: “Where Are College Presidents’ Voices on Important Public Issues?” Contrasting the way he and earlier academic leaders took stands on controversial issues with the relative silence of current presidents, Hesburgh wondered: “Where we once had a fellowship of public intellectuals, do we now have insulated chief executives intent on keeping the complicated machinery of American higher education running smoothly?”

Characteristically, Hesburgh evaluated the hesitancy to speak out in terms of its more encompassing consequence. He recalled the “contentious times” of the 1960s and ’70s, with their turmoil on campuses and across the nation at large: “Painful as those days were, however, they taught a powerful lesson: We cannot urge students to have the courage to speak out unless we are willing to do so ourselves. The true antidote to the public’s view that colleges are simply ivory towers of intellectual dilettantism is engagement with important public issues — however difficult and thorny those issues may be.”

Hesburgh’s concern for students never dimmed during his retirement years. Indeed, when he started saying no to off-campus assignments, his schedule allowed for even more student interaction. Talking in his office in 2005, he noted: “Any student is welcome here, and there’s hardly a day goes by that I don’t have two or three students. They all have different problems, and they have opportunities, and occasionally they say they haven’t been to confession in a long time. I say, ‘We can take care of that in three minutes,’ which we do.” Besides office meetings, Hesburgh also offered Mass in dormitory chapels whenever asked and frequently said the rosary with student groups.

In an irony of his retirement, the priest-academic, who began his career at Notre Dame in 1945 as a faculty member in the Department of Religion, engaged in more teaching than he’d done as president. “I teach a lot of classes,” he said. “I tell students the things I can talk about: the University and its history, science, atomic energy, civil rights, world development, peace issues and so forth. They always have something pertinent that I can address.

“I probably have taught more classes than some faculty here in the sense that I have this kind of thing happening all the time, probably at least 40 times in a semester. It’s always a different group, and it’s always fun.”

Hesburgh’s open-door policy extended beyond students to faculty, staff, alumni and campus visitors. “Everything I do now is for Notre Dame, and I give it a full run every day,” he said during our conversation in 2005. “I’m a nut on correspondence, so every letter that arrives every day is answered before I leave in the afternoon.”

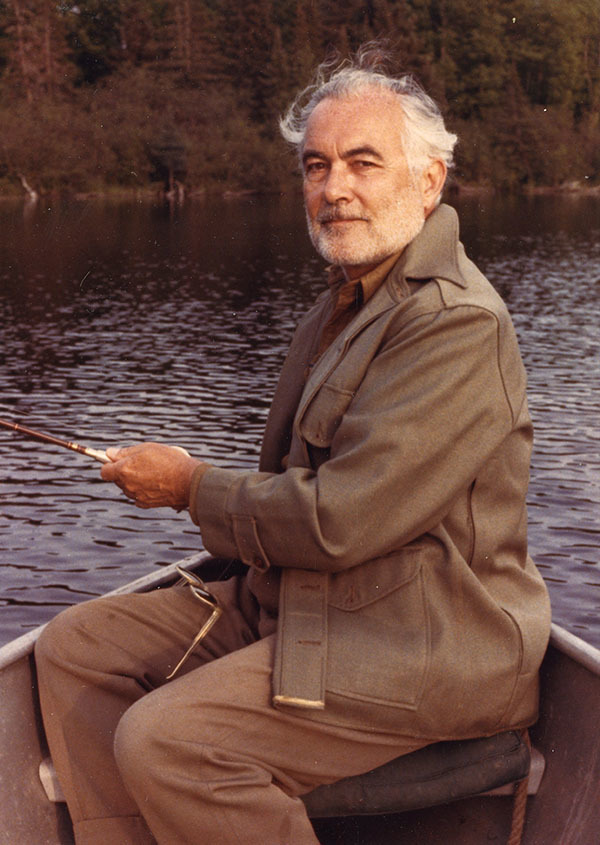

During a lifetime of posing for pictures either alone or with presidents, popes and other notables, Hesburgh preferred one with him sitting in a boat, holding a rod, and sporting a full beard. Looking enough like Ernest Hemingway’s younger brother to draw double-take comparisons.

The Notre Dame Archives is the repository of Hesburgh’s papers as well as the honorary degrees and other memorabilia. Each year of his retirement generated an average of three or four filing cabinet drawers of letters and papers.

In autumn 2004, Hesburgh fell in his residence at Corby Hall, opening a cut in his head that required medical attention. Talking with others, he decided it was time to move to Holy Cross House, an assisted living and health care facility for retired priests near Moreau Seminary on the Notre Dame campus.

After 53 years there, leaving Corby Hall, adjacent to Sacred Heart and close by the Main Building, wasn’t easy, but Hesburgh’s attitude was both realistic and future-oriented: You do what you have to do. He quickly entered into the rhythm of Holy Cross House, with its late morning Mass for the community and its daily meals for socializing. No longer able to read his breviary, he substituted three rosaries each day, often praying one before Mass and working in the others as he waited for a ride to his office or to an evening function.

During the academic year, with full afternoons devoted to work in his office and several evenings each week filled with student or University engagements, he looked forward to taking breaks during summers at Land O’Lakes, Notre Dame’s 7,500-acre, 30-lake environmental research center located on both sides of the state line between Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. For decades, Hesburgh spent a few weeks each summer there, engaging in the only hobby he loved: fishing.

“It has therapeutic effects,” he remarked. “I’m out in a boat in the middle of a lake, and it’s quiet and peaceful. No telephones. No letters. The sun is generally shining, and I’m getting sunburned, but I’m also catching fish, which is fun. You’ve got to have something for fun.”

Though the macular degeneration made fishing more difficult, he was still able to enjoy his favorite recreational pastime. “I can see enough to see the shore and to see the trees on the shore, and I don’t throw into the trees. I throw into the shore. I can see enough to fish decently if I’m casting to shore from a boat.”

During a lifetime of posing for pictures either alone or with presidents, popes and other notables, Hesburgh preferred one with him sitting in a boat, holding a rod, and sporting a full beard. Looking enough like Ernest Hemingway’s younger brother to draw double-take comparisons, the photo is featured on the cover of both hardcover and paperback editions of Travels with Ted & Ned. A framed copy was also prominently displayed in his library office.

Lasting legacy

In the essay “Self-Reliance,” 19th-century American philosopher and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man.” Hesburgh’s commitment to Notre Dame reflected the acuity of that insight, with today’s campus offering visible, named lines of that lengthened shadow: the Hesburgh Library, the Hesburgh Center for International Studies, the Hesburgh Program in Public Service, the Hesburgh Lecture Series of the Alumni Association, and so on.

Several endowed chairs bear his name, and, in 2006, Notre Dame established what are called Keough-Hesburgh Professorships to attract to campus noted scholar-teachers to advance the University’s Catholic mission and character. A gift of former chairman of the Board of Trustees Donald R. Keough and his family, Keough-Hesburgh Professorships currently exist in the Colleges of Arts and Letters, Engineering and Science.

In 2009, Mark and Stacey Yusko created the Hesburgh-Yusko Scholars Program to foster the education and development of future leaders inspired by Hesburgh’s vision and commitment. Each Hesburgh-Yusko Scholar — there are about 25 in each class — received a $25,000 merit scholarship annually throughout four undergraduate years as well as funding for four “Summer Enrichment” experiences.

Selecting the most satisfying University legacy wasn’t easy for Hesburgh, but, pressed to choose, he named the library: “I walk through here, and I see thousands of students and millions of books. When we built this place, we had 250,000 books. Now we’ve passed three million, plus two and a half million more on microfiche. That’s a lot of books.”

As he talked, Hesburgh puffed on a cigar, a habit of long-standing, always given up for Lent. Asked whether the minor indulgence creates any problem at a place that now has a no-smoking policy in every building, he said: “This is the only room in the library where I can smoke. I can’t smoke where I’m living. If someone would say to me, ‘How come you’re the only one smoking in here?’ I’d say, ‘After all, I got my name on it. After all, I got the money to build the place. After all, I built up these book collections. If I can’t smoke here, I’ll work somewhere else, where I can.’”

Although he once told the magazine Cigar Aficionado that “it’s important not to go overboard on anything — except God,” Hesburgh was willing to go just so far in adapting to life on the campus after he left the presidency. An aside about “the Puritans in the Main Building” suggested frustration more than criticism, and it was confined to a decades-old practice involving his well-established work routine.

For Hesburgh, however, God was forever the center of his life — the first word in the title of his autobiography and the only reason “to go overboard.” A priest’s priest, he constantly emphasized the power and necessity of prayer throughout his retirement years. Asserting that “one of the greatest things is just to get up every day and serve God as best you can,” Hesburgh didn’t hesitate to confront his own mortality: “I pray that when the time comes I can be as courageous about facing death as I was about facing life.”

This prayer also carried with it a personal request, one he made during the Mass celebrating the 50th anniversary of his ordination in 1993 and repeated, privately and publicly, in his later years. The “one last grace” he wanted above all others was the chance “to offer the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass every day of my life until I die. Then I’ll die happy.”

Robert Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Professor of American Studies and Journalism and director of the John W. Gallivan Program in Journalism, Ethics & Democracy at the University. His book, Fifty Years with Father Hesburgh: On and Off the Record, is forthcoming from the University of Notre Dame Press.